Classrooms, Not Carriers: Why Education Is the Primary Theatre of Today’s Power Transition

Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

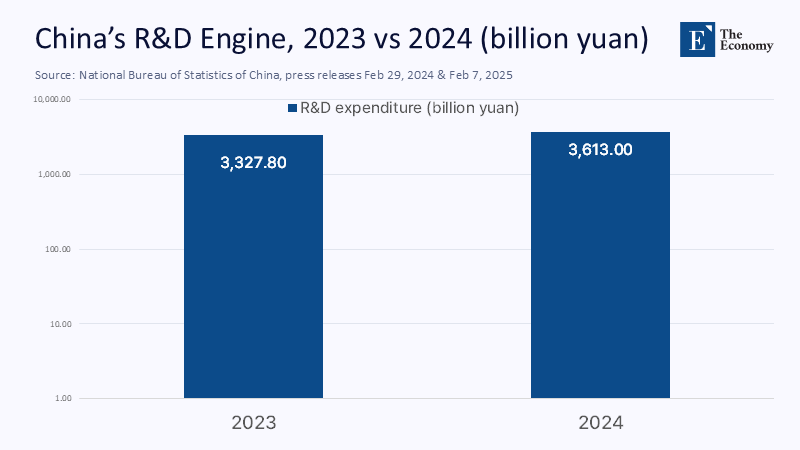

We are witnessing a redistribution of influence that is unfolding less on tarmacs and more on campuses. In February 2025, the White House budget request proposed a 93% cut to the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs—the home of Fulbright and other flagship academic exchanges—and even zeroed out Title VI and Fulbright–Hays area-studies programs at the Department of Education. Within days, a temporary pause halted many State Department exchange disbursements. Meanwhile, China vaulted to No. 2 in Brand Finance’s 2025 Global Soft Power Index, posting its highest score on record, and reported R&D expenditure topping 3.6 trillion yuan in 2024. This 8.3% annual increase signals a long-game investment in knowledge infrastructure. These three facts—America’s retreat from education diplomacy, Beijing’s rising soft-power standing, and China’s swelling research engine—explain the classroom-level front line of a geopolitical shift. If power is increasingly about who sets the syllabus, accredits the credential, and funds the scholarship, then education policy is no longer an adjunct to foreign policy. It is foreign policy. This calls for a strategic response from policymakers, educators, and stakeholders to shape the future of international education.

Reframing the Contest: From Aircraft Carriers to Admissions Offices

Washington’s pullback from people-to-people exchange—epitomized by the still-unrestarted Fulbright in China/Hong Kong, the February 2025 funding pause, and proposed deep cuts to US exchange budgets—changes the balance of influence where it matters for the next generation: classrooms, labs, vocational workshops, and standards bodies. At the exact moment, Beijing is elevating education as statecraft: inviting 50,000 young Americans over five years, expanding vocational “Luban Workshops” across the Global South, and consolidating language-teaching networks under new governance after the Confucius Institute brand’s reputational damage in the West. The result is not a sudden conversion to “benevolence” but a calculated bid to occupy vacated lanes—from scholarships to standards—especially in regions where US programs are shrinking. Reframing the moment this way matters because it shifts our policy response from abstract debates about values, such as the importance of education in shaping future leaders and fostering global understanding, to practical choices about funding, contracts, recruitment, and recognition. The contest is less “hearts and minds” in the abstract and more “bursaries and badges” in the concrete.

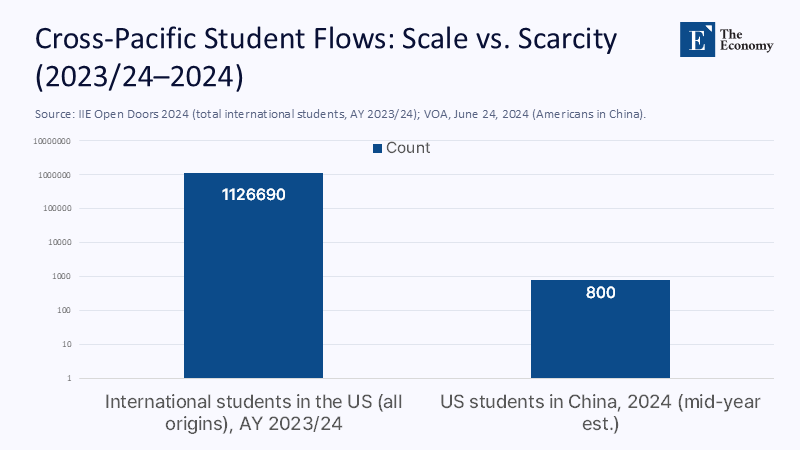

The Numbers Behind the Narrative

Quantitatively, the trend lines are stark. Brand Finance’s 2025 index places the United States and China as the world’s two most influential soft-power nations, with China overtaking the UK for the first time. Beijing’s R&D intensity rose to 2.68% of GDP in 2024, with basic research investment up 10.5% year-on-year—an underappreciated foundation for credible education offers and research tie-ups. Luban Workshops—China-funded vocational centers that embed Chinese curricula and equipment—have spread to 30+ countries, with official tallies citing 27 workshops in 23 countries as of March 2024 and subsequent press updates noting 35 in 31 by early 2025. Confucius Institutes, although shuttered across much of the US, remain globally numerous—roughly 496 in more than 160 countries in 2023—under revamped governance. On flows, the US still hosted a record 1.126 million international students in 2023/24, but Chinese enrollment there slipped while India took the top spot; in the opposite direction, fewer than 1,000 Americans are studying in China today despite Xi’s 50,000-student pledge. These are not just data points; they map where influence is accumulating and receding.

How We Estimated the Scholarship Gap—and Why It Matters

Because China no longer publishes consistent post-2019 inbound scholarship totals, we triangulated from credible proxies. Georgetown’s CSET estimates the China Scholarship Council (CSC) supports about 12% of international students in China—roughly 65,000 in a typical pre-pandemic year—and 7% of Chinese students abroad each year. We conservatively apply a 25–40% recovery factor to inbound scholarship volumes given incomplete post-COVID data and visible recruitment drives in Africa and Southeast Asia; that yields a working estimate of 16,000–26,000 CSC-funded inbound students in 2024–2025. Using published stipend norms (2,500–3,500 RMB per month) and a nine-month funded academic year, this implies an annual stipend outlay of roughly 360–820 million RMB for inbound awardees alone, excluding tuition waivers and housing subsidies. For comparison, the US appropriations snapshot shows about $741 million in new ECA appropriations in FY2025, but the FY2026 request would slash that line dramatically if enacted. Methodologically, our approach prefers official aggregates where available (NBS, State CBJ), cross-checks with sector reports (NAFSA, BEC), and applies transparent, low-bias ranges when precise counts are missing. The point is not to fetishize precision but to clarify orders of magnitude: in many Global South markets, Chinese scholarship offers are visible, predictable, and bundled with equipment and training—an integrated package the US no longer routinely matches.

The Playbook Xi Could Be Writing: Education-Statecraft in Four Moves

First, credential leadership. China is quietly scaling instruments that confer reputational gravity—HSK testing centers now exceed 1,400 worldwide—ensuring that Chinese language credentials are available, cheap, and embedded in local systems. That matters because credentials shape pipelines: students who pass HSK are the first in line for China-funded degrees, internships, and jobs in Chinese firms. Second, capability seeding via vocational hubs. Luban Workshops pair Chinese equipment with Chinese curricula and faculty development, anchoring standards in sectors like mechatronics, rail, and green energy across Africa, ASEAN, and now Latin America. Third, network persistence. Where Confucius Institutes closed in the US, many re-emerged under different labels or through local partners while remaining functionally connected to Beijing’s language-promotion machinery—fourth, flagship exchanges to soften hard edges. Xi’s pledge of 50,000 Americans is not only a soft-power play; it is a reputational hedge against escalating strategic rivalry. Each move is designed to appear benevolent while consolidating agenda-setting power in syllabi, standards, and student flows.

What This Means for Educators and Administrators

For institutions, the risk is not engagement; it is unstructured engagement. Contracts with PRC-linked funders should include unambiguous academic-freedom clauses, control over hiring and curriculum, and disclosures of all third-party funding. US and allied campuses can still partner productively with Chinese universities—especially in basic science and non-sensitive fields—but need reciprocal data-protection standards, secure data rooms for joint labs, and pathways to suspend or unwind collaborations without penalizing students. In the Global South, the pragmatic choice is often the only funded choice; that is precisely Beijing’s insight. Universities there should build consortium leverage: negotiate as regional clusters so that equipment donations, scholarships, and vocational partnerships come with maintenance guarantees, open-standard interfaces, and locally owned IP where appropriate. Teacher-training programs—China’s strong suit—should be mirrored by Western providers with transparent pedagogy standards and support for local language instruction, not just English-medium degrees. The alternative to China’s integrated offer is not moral lecturing; it is a better integrated offer.

Policy Recalibration: How Washington and Its Allies Can Compete on Value, Not Volume

Policymakers should stop treating exchange budgets as symbolic line items. The $922 million that Congress ultimately maintained for international basic education in FY2024—and the $737.6 million proposed by House appropriators in FY2026—are not rounding errors; they are the scaffolding for credible alternatives in teacher training, literacy, and girls’ education, especially where Chinese vocational and higher-ed offers now dominate public imagination. Instead of across-the-board austerity or blanket bans, the US should fund three pillars: precision scholarships in critical languages and regions (Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia), capacity-building grants for regional teacher colleges and technical universities, and standards diplomacy to keep micro-credentials and learning-outcome frameworks open and portable. Visa processing and safety advisories must be calibrated to protect security without closing the door to study in China, even as the Fulbright program to the PRC/Hong Kong remains suspended; when Washington cuts its people-to-people ties, it outsources narrative-setting to others by default.

Anticipating Critiques—and the Evidence That Answers Them

Critique one says this is alarmism because soft-power rankings are “just perceptions.” True, but perceptions drive partner choices. Brand Finance surveys 173,000 respondents across 102 markets for its 2025 index; in an era when a minister of education can announce a national policy in a WhatsApp video, perceptions and policy uptake live in the same feedback loop. Beijing’s soft-power standing is now backed by a research engine that is both growing and climbing in quality tables, with Nature Index data showing China expanding its lead in high-impact outputs in 2024. Critique two says international students flock to quality, not geopolitics. Also genuine—and China’s pitch has upgraded accordingly: sustained R&D growth, world-class labs in select fields, and scholarships that cover living costs. Critique three says that education soft power can’t change hard-power realities, such as Taiwan. Maybe not directly, but elite opinion and bureaucratic habits do shift through training, language mastery, and shared standards—factors that make coalitions either easier or harder to assemble in a crisis. That is why both Washington’s budget choices and Beijing’s scholarship calculus matter now.

Syllabus Power

Here’s the through-line back to the opening facts: when one superpower mothballs its exchange machinery and another scales a multi-billion-dollar knowledge apparatus, the space between tuition, training, and trust does not stay empty. It fills—fast—with the curriculum, credential, and cultural framing of whoever shows up. The question for educators and policymakers is not whether to engage with China’s education-statecraft, but on whose terms. The correct response is not abstention but competition: fund exchanges with guardrails, negotiate partnerships that hard-wire academic freedom and open standards, and redirect cuts into capacity-building that partners asked for. Suppose we treat education as the theatre where today’s power transition is being rehearsed. In that case, the call to action is obvious: put resources where our rhetoric is, and do it with the same discipline Beijing brings to scholarships, standards, and skills. If we fail, the next generation’s default operating system—in language, norms, and networks—will be written elsewhere.

The original article was authored by Dr Jiao Wang, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. The English version, titled "Beijing steps up as Washington steps back," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Basic Education Coalition. (2024–2025). Government relations updates and funding summaries for international basic education. Retrieved 2024–2025.

Brand Finance. (2025, Feb. 20). Global Soft Power Index 2025: China overtakes the UK; US remains top. Retrieved 2025.

China Daily. (2024, Nov. 14). China has the world’s largest vocational education system; Luban Workshops and skills competitions. Retrieved 2024.

China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe (CHOICE). (2024, Sept. 5). The demise of Confucius Institutes: Retreating or rebranding? Retrieved 2024.

Council on Foreign Relations. (2018). China’s big bet on soft power. Retrieved 2024–2025 for background.

Georgetown University, CSET. (2020). The China Scholarship Council: An overview (and related analyses). Retrieved 2025.

GAO. (2023, Oct. 30). With nearly all U.S. Confucius Institutes closed, schools cited risks and funding concerns. Retrieved 2023.

Institute of International Education (IIE). (2024, Nov. 18). Open Doors 2024: International students in the United States. Retrieved 2024–2025.

Ministry of Education, PRC. (2024, Mar. 1). China had over 47.63 million higher-education students in 2023. Retrieved 2024.

NAFSA: Association of International Educators. (2025, May 30). FY2026 funding for international education and exchange programs (summary of proposed cuts). Retrieved 2025.

NAS (National Association of Scholars). (2023–2024). After Confucius Institutes; US counts of closures and rebranded programs. Retrieved 2024.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2025, Jan.–Feb.). R&D expenditure in 2024 exceeded 3.6 trillion yuan; R&D intensity reached 2.68%. Retrieved 2025.

Place Brand Observer. (2025, Mar. 17). Global Soft Power Index 2025 methodology and results. Retrieved 2025.

State Department (US). (2024, Mar.–Apr.). FY2025 Congressional Budget Justification (Diplomatic Engagement: ECA lines) and Appendix. Retrieved 2024.

US Spending (Treasury/USAspending.gov). (2025). Educational and Cultural Exchange Programs account snapshot (019-0209). Retrieved 2025.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). (2025, Feb.). UIS Data Browser: International student mobility indicators (latest release). Retrieved 2025.

US–China exchange reporting. (2023–2025). AP, Washington Post, and The Economist coverage of US students in China and policy constraints. Retrieved 2024–2025.

VOA / FOCAC 2024 coverage; CIDCA notes; and Luban counts. (2024–2025). Chinese pledges of scholarships and training, and workshop expansion. Retrieved 2024–2025.

Xinhua / Chinese Embassy. (2023–2025). Xi’s pledge to invite 50,000 young Americans and the “Young Envoys Scholarship” rollout. Retrieved 2023–2025

Comment