Impeachment’s Uncertainty Premium: How to Protect Accountability Without Unraveling Mandates

Input

Changed

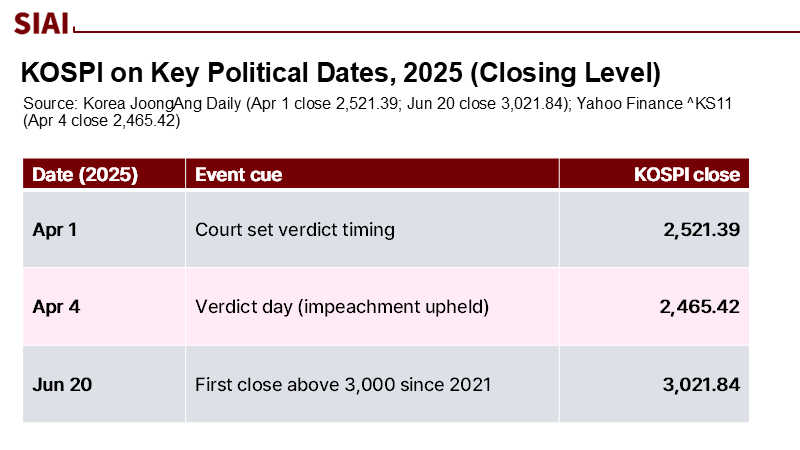

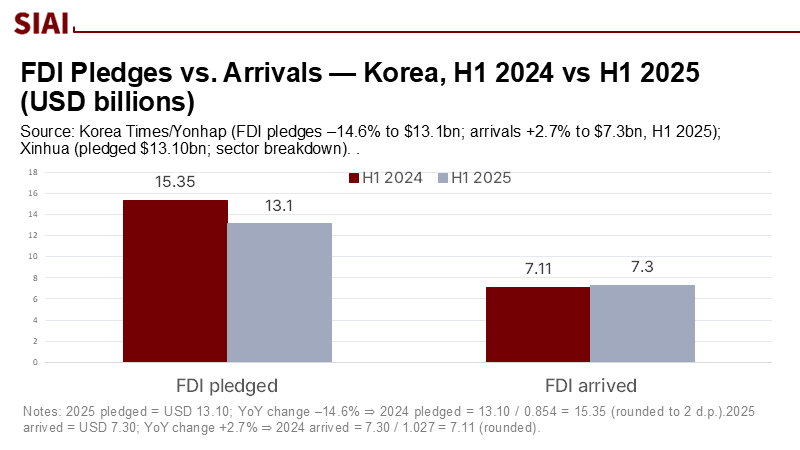

Impeachment carries an “uncertainty premium,” seen in a 14.6% drop in Korea’s FDI pledges Use impeachment as an emergency brake, not routine politics, to protect electoral mandates and stability Adopt guardrails—one-shot filings, fast voter-centered elections, judicial minimalism—and ring-fence education budgets

The most significant number for education and the economy in Northeast Asia this year is not a test score or an unemployment rate; it is 14.6 %. This figure represents the drop in pledged foreign direct investment in South Korea from the previous year in the first half of 2025, reaching $13.1 billion. At the same time, actual arrivals increased slightly. This contrast shows caution about the future instead of confidence in the present. Investors did not flee; they hesitated. They wanted to see if the country’s institutions would confirm democratic stability after a turbulent political period. This decline is not a judgment on a single leader or party. It reflects the market’s view on uncertainty—a “impeachment premium” that affects university endowments, capital budgets, and the funding that supports scholarships, teacher salaries, and research grants. When democracies use impeachment as a routine tool rather than an emergency measure, they complicate their own predictability.

A safeguard, not a habit

Impeachment is a constitutional fix, not a political weapon. When used responsibly, it protects the rule of law. However, frequent use risks turning judicial review and legislative standoffs into a regular bypass of the ballot box. South Korea's 2025 crisis highlighted this issue. The Constitutional Court unanimously supported the impeachment of the sitting president on April 4, 2025, leading to a compressed timeline for a special election on June 3. This shifted political authority from a five-year term to a two-month rush. Courts, legislators, and a mobilized public followed formal procedures. However, the overall impact was clear: a small court ruling and tight schedule ended a national mandate years early. If this pattern becomes common in any democracy, citizens will view elections as temporary, while investors will see long-term policies as fragile.

The Philippines presents a contrasting situation of similar institutional strain. On July 25, 2025, the Supreme Court ruled against an impeachment complaint against the vice president, declaring it unconstitutional due to a restriction on multiple filings within a year. Less than two weeks later, the Senate officially shelved the case, effectively concluding the attempt. In formal terms, this outcome respected the rules. In political terms, it conveyed a different message: the judiciary can override legislative actions before the public even sees the evidence. When courts and legislatures alternate between approvals and rejections at the highest level, the public observes proceedings but experiences inconsistency. This inconsistency is not abstract; it shows up in discount rates, delayed capital plans on campuses, and increased borrowing costs for regional education projects.

Respecting the democratic process is essential for credibility. Frequent leadership changes undermine that credibility, even without impeachment. Japan's latest leadership shift—another prime minister resigning within a year—revives memories of an era of instability that weakened policy signaling. If a prime minister’s tenure is uncertain, medium-term reforms in skills, science funding, and university governance struggle to gain traction. When impeachment and resignation cycles coincide with divisive media environments, the public starts to view institutions as combatants rather than mediators. That is when the impeachment tool turns into a habit—and habits can be risky.

The cost of serial impeachments: a new uncertainty premium

The data now shows a clear trend. The 14.6 percent drop in investment pledges signals a pause for the future, while the 2.7 percent rise in actual arrivals reflects completed deals from the past. Together, they suggest a postponement, not an exodus. A similar mixed signal emerged in Korean stocks. Markets fluctuated wildly around the Constitutional Court's ruling—surging over 2,500 temporarily during the announcement before dropping—then rallied after the election but stalled with later policy updates. Volatility stems from information gaps, and impeachment, by its nature, creates a significant divide between past mandates and future policies.

A brief note on methodology helps clarify these signals in policy terms. Pledged foreign direct investment (FDI) serves as a proxy for expectations regarding institutional stability over the next three to five years—the duration of most capital projects with educational benefits like labs, training centers, and partnerships in education technology. Arrivals indicate the execution of previous commitments. When pledges decline while arrivals remain steady, it typically means boards have pressed “pause” on new long-term investments until succession rules are clear. The finance ministry’s measures in January to ease foreign-exchange trading aimed to reduce the cost of this waiting, while a manufacturing PMI dip highlighted the domestic demand challenges that political uncertainty could worsen. This situation is not disastrous, but it is costly.

Credit markets conveyed a similar message—no panic, but a notable increase in risk. Sovereign five-year CDS widened during the late-2024 crisis but returned to around thirty basis points by mid-February 2025, a level more in line with investment-grade stability than systemic distress. Global evidence suggests that political shocks increase sovereign risk premiums more significantly in emerging markets and economies affected by trade disputes. Korea is positioned at the crossroads of both issues due to its extensive supply chains in the chip, automotive, and platform economy sectors. In simpler terms, one impeachment per generation is manageable; however, a cycle of impeachments, or the expectation of one each term, introduces a structural uncertainty premium that affects everything from student loan rates to the costs of municipal bonds for school construction.

How outside factors are perceived is just as crucial as internal processes. When a U.S. president describes South Korea as “unstable,” even momentarily, it resonates through asset committees, trade negotiators, and university exchange programs. Economists might point to positive data—post-election stock market gains, better leading indicators—but perception and headline risks significantly impact short-term capital costs. The OECD’s mid-year forecast, which projected just 1.0 percent growth for 2025 due to tariffs and uncertainty, captured this environment. Clear policies restore momentum; ongoing process disruptions drain it. Therefore, the importance of clear policies in restoring economic momentum cannot be overstated.

This uncertainty premium is not a vague concept for education systems. University hospitals rely on stable bond markets for upgrades; public universities need reliable funding; vocational institutions count on co-funded training programs with industries. Each bit of uncertainty raises the gap between bids and asks on public contracts, increases contingency margins on public-private partnerships, and delays approvals for scholarships tied to corporate funding. The losses to democracy are subtler: when courts or emergency votes repeatedly determine leadership, civics education struggles to explain to students why long-term mandates matter. However, educational institutions play a crucial role in this. They can empower students with the knowledge and understanding of why long-term mandates matter, thereby contributing to the rebuilding of trust that was once lost, which is costly, and education ultimately bears that expense.

Reforms that protect accountability without taxing democracy

The aim is not to weaken impeachment; it is to clarify and discipline its use. Democracies can create institutional boundaries that separate serious accountability from everyday politics. Three changes could achieve this quickly.

First, implement a one-time integrity rule. Adapt the idea behind the Philippines’ “one-year bar” on multiple impeachment complaints to tackle the issue of ongoing impeachment. Establishing a constitutional requirement that any impeachment effort within a presidential term must consolidate all accusations into a single article, with strict evidence standards and a set timeline, would put an end to continuous filings aimed at keeping leaders uneasy. Courts should verify the completeness and timeliness of the filing while leaving political judgment to supermajorities and, when feasible, to voters. The Philippine Court’s ruling on July 25 focused on process rather than resolving the underlying accusations—and this distinction is beneficial.

Second, create timelines that respect mandates. If impeachment affects a mandate, voters should be able to re-establish it quickly and predictably. South Korea’s rushed timeline to a special election could serve as one model, but it arose out of necessity rather than foresight. Constitutions and election laws should embed a tight window—perhaps 60 to 90 days—for a national vote to provide a new mandate, rather than prolonging a caretaker period. Parliament could be granted limited interim budget powers focused solely on essential services and pre-approved expenditures for schools and universities. Markets can adjust to uncertainty, but they struggle with a lack of direction.

Third, courts should limit their focus to essential questions—like constitutionality, due process, and jurisdiction—as the Philippine Supreme Court did by voiding the improper filing. Courts should avoid making findings that replace political accountability with judicial rulings, unless the Constitution demands it. Where facts are disputed but impeachment is unwarranted, recall or confidence vote mechanisms offer an electoral route that respects original mandates while allowing citizens to pivot. This method distributes legitimacy costs across institutions rather than concentrating them within a judicial panel.

Policy communication can strengthen these safeguards. Finance ministries and central banks should commit to maintaining continuity for ongoing capital projects in education—protecting scholarship budgets, research grants, and school construction from political instability unless a new parliament explicitly votes to cancel them. Regulators can issue guidance during impeachment periods that extend trading hours and keep liquidity options available, as Korean authorities did in early 2025. Each of these actions reduces the costs of uncertainty and lessens the impact of risk premiums.

Lastly, leaders should avoid framing impeachment as a win or loss. It should be seen as a failure—either of conduct or of coalition management—that institutions should resolve without causing lasting damage to legitimacy. When prominent politicians label allied democracies as “unstable,” they turn domestic power disputes into reputational crises. Education leaders can play a crucial role in this effort: schools and universities are where constitutional knowledge is developed, where future officials learn the distinction between aggressive tactics and institutional harm. Impeachment should not become a civics lesson in shortcuts.

The 14.6% indicates how cautious capital has pulled back from new investments in the first half of 2025. It serves as a warning. Democracies that normalize impeachment as a political strategy will face higher risk premiums, postponed investments, and a gradual decline in legitimacy that courts cannot restore unaided. The more straightforward path involves treating impeachment as a one-time remedy for serious offenses, ensuring quick and voter-focused elections when it occurs, instructing courts to oversee procedures rather than determine outcomes, and protecting long-term education and research funding from transient political shifts. None of these steps undermines accountability. Instead, they reinforce the importance of the ballot while keeping a constitutional safety mechanism available. If policymakers act on these changes now—setting timelines, tightening rules, and ensuring continuity—students and educators will notice the impact first. The uncertainty premium will decrease. Future shocks will dissipate more rapidly. The mandate, rather than political maneuvering, will once again define democratic power.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Press. (2025, July 25). Philippine Supreme Court rules impeachment bid against vice president is unconstitutional.

Axios. (2025, August 25). Trump eases tone on South Korea instability after meeting President Lee (news post and report).

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2025, April 11). Yoon’s impeachment and South Korea’s future.

Financial Times. (2025, September 8). Political instability jolts Japan.

International Monetary Fund. (2025, April). Global Financial Stability Report—Chapter 2: Geopolitical risks and asset prices.

International Monetary Fund. (2025, February 6). IMF Executive Board Concludes 2024 Article IV Consultation with the Republic of Korea (Press Release No. 25/30).

KED Global. (2025, February 17). S. Korea’s default risk dips below pre-martial law levels.

Korea JoongAng Daily. (2025, April 1 & April 4). Kospi rebounds with impeachment ruling announcement; Kospi seesaws during Constitutional Court’s verdict.

Korea.net (Government of the Republic of Korea). (2025, July 4). FDI arrivals to Korea rise 2.7% in H1 2025 (Press release).

Korea Times/Yonhap. (2025, July 3). FDI pledges to Korea down 14.6% in first half on trade, political uncertainties.

OECD. (2025, June 3). Economic Outlook 2025/1—Korea chapter.

Reuters. (2024, December 3–4). Investor reaction to South Korea’s political crisis (2025, January 2). South Korea to spur foreign inflows, consumer demand amid political crisis.

Reuters. (2025, July 25). Philippine Supreme Court voids impeachment complaint against VP Duterte; ABS-CBN News. (2025, August 6). Senate archives Sara Duterte impeachment case.

Tamase, Paolo S., and Athena Charanne Presto. Dribbling institutions and the Duterte impeachment. East Asia Forum, 6 September 2025.

Comment