From Parrots to Partners: A Policy Blueprint for AI-Literate Learning

Published

Modified

AI use is ubiquitous; current assessments reward fluency over thinking Grade process, add brief vivas, and require transparent AI-use disclosure Train teachers, ensure equity, and track outcomes to make AI a partner

Eighty-eight percent of university students report they now use generative AI to prepare assessed work, an increase from just over half a year ago. This significant shift in AI usage, while promising, also raises concerns. Nearly one in five students admits to pasting AI-generated text, whether edited or not, directly into their submissions. At the same time, new PISA results show that about one in five 15-year-olds across OECD countries struggle even with simpler creative-thinking tasks. This data highlights the need for a balanced approach to AI integration in education. The current trend reveals a growing disparity between the speed at which students can produce plausible text and the slower, more challenging task of generating ideas and making informed judgments. When we label chatbots as 'regurgitators,' we risk overlooking the real issue: a system that rewards fluent output over clear thinking, tempting students to outsource the work that learning should reinforce. The goal should not be to ban autocomplete; it should be to make cognitive effort noticeable again and valuable.

What We Get Wrong About "Regurgitation"

Calling large language models parrots lets institutions off the hook. Students respond to the incentives we create. For two decades, search engines have made copying easy; now language models make it quick to paraphrase and structure ideas. The issue isn't that students have suddenly become less honest. Many assessments still value smooth writing and recall more than the products of reasoning. Consider what educators report: a quarter of U.S. K-12 teachers believe AI does more harm than good, yet most lack clear guidance on how to use or monitor it. Teacher training is increasing but remains inconsistent. In fall 2024, fewer than half of U.S. districts had trained teachers on AI; by mid-2025, only about one in five teachers reported that their school had an AI policy. Confusion in the classroom translates into ambiguity for students. They will do what feels normal, quick, and safe.

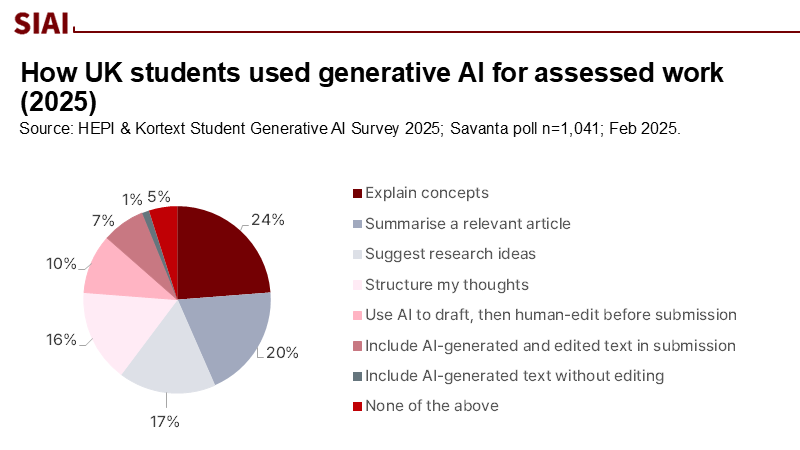

The common, fast, "safe" use case is for ideation and summarization, not careful drafting. UK survey data from early 2025 indicate that the most frequent uses by students are explaining concepts and summarizing articles; using AI at any stage of assessment has become the standard rather than the exception. Teen usage for schoolwork is on the rise, but is still far from universal, suggesting a spread pattern where early adopters set norms that others follow under pressure. If we tell students to "use it like Google for ideas, not as a ghostwriter," we must assess in a way that clearly shows the difference. Right now, many find it hard to see a practical distinction. As detection methods become uncertain—and many major vendors avoid issuing low AI "scores" to minimize false positives—monitoring output quality alone cannot ensure academic integrity. We need a better design at the beginning.

The deeper risk isn't just copying; it's cognitive offloading. Several recent studies and evaluations, ranging from classroom surveys to EEG-based laboratory work, suggest that regular reliance on chatbots diverts mental effort away from planning, retrieval, and evaluation processes where learning actually occurs. These findings are still early and not consistent across tasks, but the trend is clear: when we let models draft or make decisions, our own attention and self-reflection can weaken. This doesn't mean AI cannot be helpful; it means we need to create tasks where human input is necessary and valued.

The Evidence—And What It Actually Implies

If 88% of students now use generative tools at some stage of assessment and 18% paste AI-generated text, we need to grasp the patterns behind these numbers. The same UK survey shows that the main uses dominate, with a quarter of students drafting with AI before making revisions; far fewer copy unedited text. In short, "regurgitation" isn't the average behavior, but it is a visible trend—and it becomes tempting in courses that reward speed and surface fluency. A Guardian analysis of misconduct cases in the UK shows that confirmed AI-related cheating increased from 1.6 to 5.1 per 1,000 students year-over-year, while traditional plagiarism declines; universities admit that detection tools struggle, and more than a quarter still do not track AI violations separately. Relying solely on enforcement cannot fix what assessment design encourages. (Method note: the Guardian figure combines institutional returns and likely undercounts untracked cases, potentially understating the actual issue.)

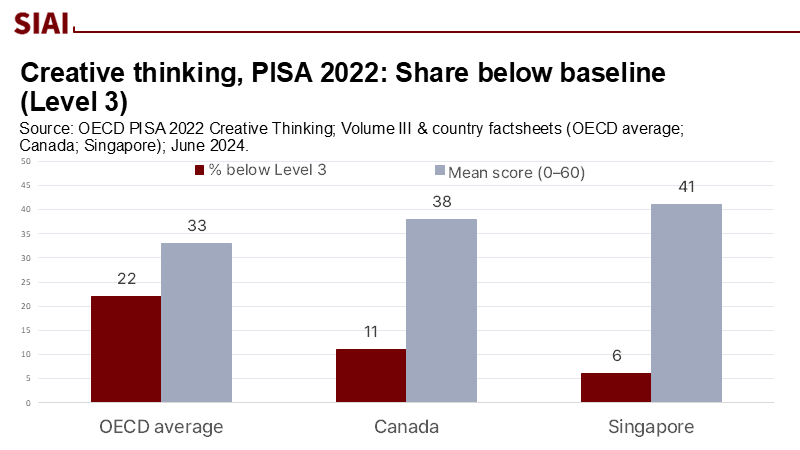

When we compare student abilities, we see the tension. In PISA 2022's first creative-thinking assessment, Singapore led with a mean score of 41/60; the OECD average was 33, and about one in five students couldn't complete simpler ideation tasks. Creative-thinking performance correlates with reading and math, but not as closely as those core areas relate to each other, suggesting that both practice and teaching—not just content knowledge—shape ideation skills. If AI speeds up production but our system does not clearly teach and evaluate creative thinking, students will continue to outsource the very steps we neglect.

What about the claim that AI is simply making us worse thinkers? Early findings are mixed and depend on context. Lab work from MIT Media Lab indicates reduced brain engagement and weaker recall in writing assisted by LLMs compared to "brain-only" conditions. Additionally, a synthesis notes that students offload higher-order thinking to bots in ways that can harm learning. Yet other studies, especially in structured settings, show improved performance when AI handles the routine workload, allowing students to focus their efforts on analysis. The key factor isn't the tool; it's the task and what earns credit. (Method note: many studies rely on small samples or self-reports; the best assumption is directional rather than definitive.)

Meanwhile, educators and systems are evolving, though unevenly. Duke University's pilot program offers secure campus access to generative tools, enabling the testing of learning effects and policies on a larger scale. Stanford's AI Index chapter on education notes an increasing interest among teachers in AI instruction, even as many do not feel prepared to teach it. Surveys through 2025 indicate that teachers using AI save time, and a growing, albeit still minority, share of schools have clear policies in place. In short, the necessary professional framework is developing, but slowly and with gaps. Students experience this gap as a result of mixed messages.

We should also be realistic about detection methods. Turnitin's August 2025 update specifically withholds percentage scores below 20% to reduce false positives, acknowledging that distinguishing between model-written and human-written text can be challenging at low levels. Academic integrity cannot depend on a moving target. Instead of searching for "AI DNA" after the fact, we can create assignments so that genuine thinking leaves evidence while it happens.

A Blueprint for Cognitive Integrity

If the ideal scenario is to use AI like a search tool—an idea partner rather than a ghostwriter—we need policies that make human input visible and valuable. The first step is to grade for process. Require a compact "thinking portfolio" for major assignments: a log of prompts used, a brief explanation of how the tool influenced the plan, the outline or sketch created before drafting, and a quick reflection on what changed after receiving feedback. This does not need to be burdensome: two screenshots, 150 words of rationale, and an outline snapshot would suffice. Give explicit credit for this work—perhaps 30–40% of the grade—so that the best way to succeed is to engage in thinking and demonstrate it. When possible, conclude with a brief viva or defense in class or online: five minutes, with two questions about choices and trade-offs. If a student cannot explain their claim in their own words, the problem lies in learning, not the software. (Method note: for a 12-week course with 60 students, two five-minute defenses per student add roughly 10 staff hours; rotating small panels can help manage this workload.)

The second step is to reframe tasks so that using ungrounded text is insufficient. Swap purely expository prompts with "situated" problems that require local data, classroom materials, or course-specific case notes that models will not know. Ask for two alternative solutions with an analysis of downsides; require one source that contradicts the student's argument and a brief explanation of why it was dismissed. Link claims to evidence from the course content, not just to generic literature. These adjustments force students to think within context, rather than just producing fluent prose.

Third, normalize disclosure with a simple classification. "AI-A" means ideation and outlining; "AI-B" refers to sentence-level editing or translation; "AI-C" indicates draft generation with human revision; "AI-X" means prohibited use. Students should state the highest level they used and provide minimal supporting materials. This treats AI like a calculator with memory: allowed in specific ways, with work shown, and banned where the skill being tested would be obscured. It also provides instructors with a common language, enabling departments to compare patterns across courses. (Method note: adoption is most effective when the classification fits on one rubric line, and the LMS provides a one-click disclosure form.)

Fourth, build teacher capacity quickly. Training at the district and campus levels increased in 2024, but it still leaves many educators learning on their own. Prioritize professional development on two aspects: designing tasks for visible thinking and providing feedback on process materials. Time saved by AI for routine preparation—which recent U.S. surveys estimate at around 1–6 hours weekly for active users—should be reinvested into richer prompts, oral evaluations, and targeted coaching. Teacher time is the most limited resource; policies must protect how it is used.

Fifth, address equity directly. Student interviews in the UK reveal concerns that premium models offer an advantage and that inconsistent policies across classes are perceived as unfair. Offer a baseline, institutionally supported tool with privacy safeguards; teach all students how to evaluate outputs; and ensure that those who choose not to use AI are not penalized by tasks that inherently favor rapid bot-assisted work. Gaps in creative thinking based on socioeconomic status indicate that we should prioritize practice that mitigates literacy bottlenecks—through visual expression, structured ideation frameworks, and peer review—so every student can develop the skills AI might distract them from.

Finally, measure what matters. Track the percentage of courses that evaluate process; the share employing short defenses; the distribution of student AI disclosures; and changes in results on assessments that cannot be faked by fluent text alone. Expect initial variation. Anticipate some resistance. But we make the human aspects of learning clear and valuable. In that case, the pressure to outsource will decline automatically in areas where we still need supervision—like professional licensure exams, clinical decisions, or original research—limit or prohibit generative use and explain the reasoning. The aim is not uniformity but clarity matched to the proper skills being assessed.

None of this requires waiting for standards bodies to take action. Universities can begin this semester; school systems can test it in upper-secondary courses right away. Institutions are already implementing this, with secure campus AI portals being tested in the U.S. and OECD member countries, which provide practical guidance on classroom use. Our policies should reflect this practicality: no panic or hype, just careful design.

The initial figure—eighty-eight percent—will only increase. We can continue to portray the technology as a parrot and hope to catch the worst offenders afterward, or we can adjust what earns grades so that the safest and quickest path is to think. The creative-thinking results remind us that many students need practice in generating and refining ideas, not just improving sentences. If we grade for process, hold small oral defenses, and normalize disclosure, we transform AI into the help it should be: a quick way to overcome obstacles, not a ghostwriter lurking in the shadows. This approach aligns incentives with learning honestly. It respects students by asking for their judgment and voice. It values teachers by compensating them in time for deeper feedback. And it reassures the public by ensuring that when a transcript indicates "competent," it means the student actually completed the work as required. The tools will continue to improve. Our policies can, too, if we design for visible thinking and view AI as a partner we guide, rather than a parrot we fear.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2025, September 6). Duke University pilot project examining pros and cons of using artificial intelligence in college.

Gallup & Walton Family Foundation. (2025, June 25). The AI dividend: New survey shows AI is helping teachers reclaim valuable time.

Guardian. (2025, June 15). Revealed: Thousands of UK university students caught cheating using AI.

HEPI & Kortext. (2025, February). Student Generative AI Survey 2025.

Hechinger Report. (2025, May 19). University students offload critical thinking, other hard work to AI.

MIT Media Lab. (2025, June 10). Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt from LLM-Assisted Writing.

OECD. (2023, December 13). OECD Digital Education Outlook 2023: Emerging governance of generative AI in education.

OECD. (2024, June 18). New PISA results on creative thinking: Can students think outside the box? (PISA in Focus No. 125).

OECD. (2024, November 25). Education Policy Outlook 2024.

Pew Research Center. (2024, May 15). A quarter of U.S. teachers say AI tools do more harm than good in K-12 education.

Pew Research Center. (2025, January 15). About a quarter of U.S. teens have used ChatGPT for schoolwork—double the share in 2023.

RAND Corporation. (2025, April 8). More districts are training teachers on artificial intelligence.

Stanford HAI. (2025). The 2025 AI Index Report—Chapter 7: Education.

Turnitin. (2025, August 28). AI writing detection in the new, enhanced Similarity Report.

Comment