When Good Intentions Become High-Value Targets: Rewiring Aid for Political Risk

Input

Changed

Aid can raise political violence by making public office a richer prize Design fixes—timing, transparency, smaller discretion, cash or in-kind by context—reduce that risk Gaza shows the stakes: build neutral, auditable rails and protect multi-year humanitarian budget

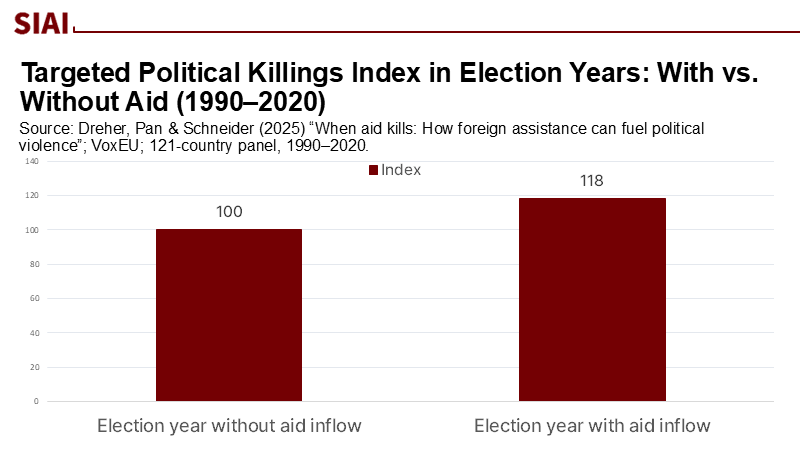

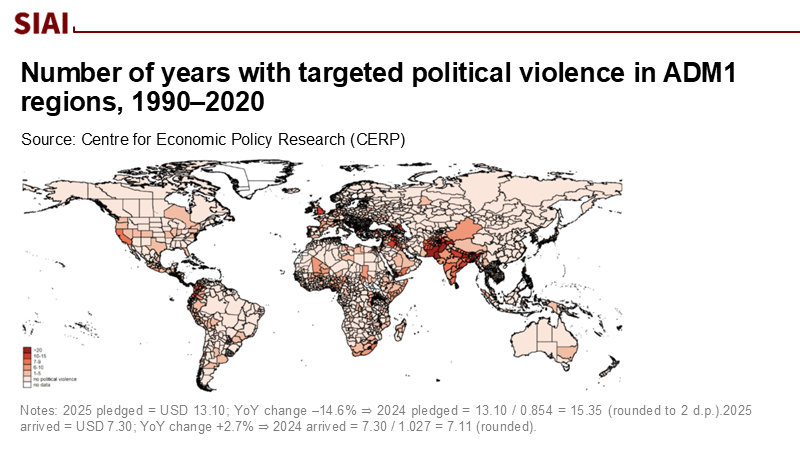

The most alarming figure in today’s aid discussion is not how much money donors send, but rather what happens to politics where that money goes. According to a recent study of 121 countries from 1990 to 2020, areas receiving foreign aid saw a 15 to 20% increase in targeted killings of politicians during the years that aid arrived. The risks are exceptionally high around election times and in places with weak governance. Aid can unintentionally increase the stakes for control over public office by turning budgets, contracts, and local projects into valuable prizes. This insight reframes the typical debate over whether aid “works.” If money serves as a political resource, the way we design, time, and channel it will either reduce those violent incentives or intensify them. Amid cuts—global official development assistance (ODA) fell in real terms in 2024 for the first time in six years—getting this design right is not just a moral issue but also a security concern. The urgency and significance of the decisions on aid design and timing cannot be overstated.

Aid as a Prize, Not Just a Lifeline

Familiar narratives often portray aid as a straightforward channel from generous donors to vulnerable families. However, the reality is more complex: aid is a powerful tool that can shift the balance of power. The VoxEU analysis suggests that when funds flow into fragile areas during election cycles, targeted attacks on politicians increase. This indicates that local actors view aid flows as a means of influencing job allocation, procurement, and patronage. The mechanism is precise: projects create revenue streams, making the offices that manage these streams more valuable. In areas with little oversight, violence can be a way to secure access. This doesn’t mean aid is harmful overall; rather, the political economy of aid delivery is crucial to outcomes. Policy must evolve to focus not just on counting schools or clinics but on understanding the incentives created by aid as it moves from donors to communities.

We must also consider the political economy on the donor side. In 2024, humanitarian aid decreased by about 9.6%, while ODA for refugee costs inside donor countries accounted for 13.1% of total DAC ODA (USD 27.8 billion). Budget cuts within donor agencies and reallocations to domestic needs shrink the flexible resources available where the risk of violence is highest. If donors redirected just three percentage points of ODA from in-country costs back to external operations, approximately USD 6.3 to 6.4 billion (3% of the 2024 ODA budget, around USD 212.1 billion) could go to frontline settings. This estimate multiplies 0.03 by the 2024 ODA total; figures from the OECD and independent trackers align closely. The exact total will vary with revisions, but the magnitude is relevant for policy.

A second design lesson involves modality. Recent reviews suggest that, where feasible, cash-based aid often provides quicker relief with less distortion and can help alleviate certain forms of violence by reducing immediate economic stress. These are not catch-all solutions: cash requires functioning markets, secure payment systems, and reliable verification. However, in locations where in-kind aid can be taxed, seized, or resold by armed groups, offering digital cash to verified recipients, along with protection services, can reduce the financial incentives for violent interference.

Designing Out the Violence

Since aid can increase the stakes of political control, the first rule is to keep timing non-political. Donors should avoid large disbursements in the months before national or local elections in fragile environments unless the support is life-saving and can be secured through neutral channels. The VoxEU study highlights that the risks of violence often coincide with elections. Adjusting the timing is a straightforward, usually no-cost measure. When crises necessitate spending during these periods, donors should employ methods that minimize capture, including direct cash transfers to individuals via audited e-payment systems, third-party monitoring with public dashboards, and contracts that automatically pause in the event of sudden changes in beneficiary lists.

Next, control should be removed from discretionary bottlenecks. When governors or district leaders can steer project funds to their supporters, targeted attacks become an investment. Donors should limit local discretionary procurement above small amounts and promote transparent, rules-based allocations linked to clear indicators—like poverty rates, displacement intensity, or school closure days—updated monthly. This emphasis on transparent, rules-based allocations is not just about reducing the risk of violence, but also about ensuring accountability and fairness in aid distribution. Publish allocations and delivery logs in accessible formats for independent journalists and civic groups. The goal is not to punish local actors, but to diminish the value of the office by reducing the financial rewards associated with it. This approach aligns with a broader lesson from development-conflict discussions: as the value of seizing aid decreases, so does the incentive for violence.

Third, expand cash where markets function and pair it with protection where they do not. A series of studies from 2024 to 2025 indicate benefits from multi-purpose cash and improved health and protection outcomes when cash is part of case management—especially for survivors of gender-based violence. The practical interpretation is this: when markets can supply food and water if households have purchasing power, cash is more effective than convoys passing through checkpoints. However, if markets fail or siege conditions restrict supplies, cash alone won’t suffice. In those cases, focus on negotiating humanitarian access, establishing safe corridors, and delivering services with real-time monitoring. Program design should be flexible: start with small-value digital cash and services, monitor prices and delivery issues, and adjust to in-kind provisions as necessary.

Fourth, protect humanitarian funds from the political cycles in donor countries. The 2024 data shows just how quickly external operations can be squeezed by domestic budgetary challenges. Implement multi-year humanitarian budgets with automatic stabilizers that activate when conflict-related displacement or acute malnutrition surpass agreed thresholds. Limit the share of ODA that can be allocated as in-country refugee costs during times of increased demand, with sunset clauses. These measures won’t eliminate politics but will safeguard life-saving budgets from reallocations that leave frontline agencies in a tough spot. The need for stability and continuity in aid funding is crucial for ensuring the effectiveness of humanitarian efforts, and this is a key concern for security analysts.

Gaza as an Extreme Stress Test

Gaza highlights many failures associated with politicized aid: total war, near-impossible access constraints, deep mistrust among parties, and claims that aid is being blocked or diverted. In early 2024, several major donors paused funding to UNRWA after allegations of staff involvement in Hamas’s October 7 attack; others resumed giving after conducting reviews. Meanwhile, humanitarian needs escalated, with repeated U.N. warnings of famine risk as aid deliveries lagged demand. In this context, claims of diversion became widespread. A July 2025 USAID analysis found no evidence of widespread theft of U.S.-funded aid by Hamas, based on over 150 incident reviews. Conversely, Israeli authorities claimed that up to 25% of supplies were seized or resold, citing intelligence. The disparity between these assessments is significant. The policy response should not favor one party instinctively; it should prepare for the worst-case scenario while measuring actual conditions. This means creating aid flows that are both difficult to capture and easy to audit in real-time, even as agencies work to gain access.

How does this look in practice? First, use neutral systems wherever possible: route assistance through digitized beneficiary registries validated by multiple sources, e-vouchers that can be redeemed at vetted merchants, and biometric checks conducted by independent operators with strong privacy safeguards. Second, increase transparency: create public, daily dashboards that report cleared trucks, tonnage delivered, unique beneficiaries paid, median redemption times, and prices of a standard food basket in key markets. Third, implement adaptive triggers: if prices spike or redemption rates drop in certain areas, the system should automatically adapt—such as increasing in-kind water or fuel supplies and reducing cash—until conditions stabilize. These are not just theoretical adjustments; versions of each have been successfully used in other complex emergencies and serve as adequate safeguards against political interference.

Another key issue is donor confidence. UNRWA’s crisis demonstrated how rapidly a single allegation can freeze essential funding. In 2023, the U.S. and EU covered about three-quarters of UNRWA’s core budget; when they halt funding, services collapse. The solution lies in diversifying channels and building redundancy into systems that reach schools, clinics, and shelter support. If an agency encounters a temporary pause, pre-authorized back-up channels with other U.N. bodies or vetted NGOs can maintain minimum services using escrowed funds managed by an independent fiduciary agent. This is not bureaucratic excess; it serves as a political risk hedge that shields humanitarian functions from reputational damage while investigations unfold.

Gaza also reveals the limits of relying solely on cash. Cash has clear advantages when goods are available; however, when borders are closed or supplies are destroyed, only physical delivery works. This requires a step-by-step approach: secure corridors and fuel for logistics first, followed by cash and vouchers, with service contracts for trauma care and education operating simultaneously. Data should guide these decisions. Suppose daily U.N. or third-party monitors report that truck deliveries have fallen below planned volumes for a week. In that case, pre-established protocols should reallocate resources to non-monetizable items—such as water purification and medical oxygen—until access improves. This rules-based approach to humanitarian assistance reduces opportunities for political interference and diminishes the value of aid as a prize to compete over.

The Gaza situation should not overshadow broader priorities. The same design principles—timing disbursements away from election periods, minimizing local discretion, publishing detailed, easily accessible logs, scaling cash with protections where possible, and securing multi-year funding—apply across fragile states from the Sahel to parts of Southeast Asia. The global context is tightening: donors have reduced their spending in 2024, humanitarian budgets have decreased, and the share of ODA spent internally within donor countries remains historically high. Yet, the need for effective aid continues to grow. This is when thoughtful design and governance are most crucial.

We began with a striking statistic: a 15 to 20% rise in targeted killings of politicians during years when aid arrives in fragile contexts. If that is the risk, the answer is not to withdraw support. Instead, we should treat aid like any powerful tool that can cause harm if mismanaged: implement safeguards around how and when it operates—time-significant transfers outside of election cycles, when possible. Remove discretion from bottlenecks and publish detailed records from approval to delivery. Utilize cash when markets function and apply protections as needed; rely on in-kind support when they do not. Shield humanitarian budgets from the political pressures in donor capitals. In complex situations like Gaza, design delivery systems that anticipate conflicts while still saving lives. By doing so, aid can become less of a target worth fighting over and more of the lifeline we intend. The choice is not between generosity and realism. It is about integrating the two so that life-saving funds do not also endanger those elected to serve their communities.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

ABC News. (2025, July 26). USAID analysis finds no evidence of widespread aid diversion by Hamas in Gaza.

AidData. (2024). Aiding War: Foreign Aid and the Intensity of Violent Armed Conflict.

American Jewish Committee (AJC). (2024). Humanitarian Aid in Gaza: What’s Really Happening.

CFR (Council on Foreign Relations). (2024). The UN’s Palestinian Aid Controversy: What’s at Stake.

CONCORD. (2024). AidWatch 2024: In-donor refugee costs in EU ODA.

CSIS. (2025). Experts React: Starvation in Gaza.

Dreher, A., Pan, J., & Schneider, C. (2025, Sept. 6). When aid kills: How foreign assistance can fuel political violence. VoxEU.

Eurodad. (2025). Preliminary Aid 2024: Aid crisis—new data sounds alarm.

Focus 2030. (2025). Historic drop in Official Development Assistance in 2024.

J-PAL. (2025). The Evidence Effect: Evidence for action in conflict and crisis.

Lancet (Cavalcanti et al.). (2025). Evaluating the impact of two decades of USAID interventions.

OECD. (2025, Apr. 16). Official development assistance: 2024 figures and press release.

OECD. (2025, Apr. 16). Preliminary ODA levels in 2024 (DCD(2025)6).

Our World in Data. (2025). Foreign aid can be a large share of income during crises.

Reuters. (2025, July 25). USAID analysis found no evidence of massive Hamas theft; Israeli military alleges up to 25%.

UNHCR. (2024). Cash-Based Interventions 2023 Overview.

UNRWA. (2024–2025). Donor charts and funding trends.

VoxDev. (2025). Can public policy prevent conflict and violence?

World Bank. (2025). Results and Performance of the World Bank Group 2024; FCV Strategy 2020–2025.

Comment