A Narrow Channel: East Asia’s Pragmatic Pivot Under Tariff Shock

Input

Changed

Tariffs and chip controls are forcing a pragmatic Japan–Korea thaw Ishiba and Lee, both China-leaning, hedge via Beijing while keeping U.S. security ties Fragile and transactional, this shift will redirect trade, tech, and student flows in 2025

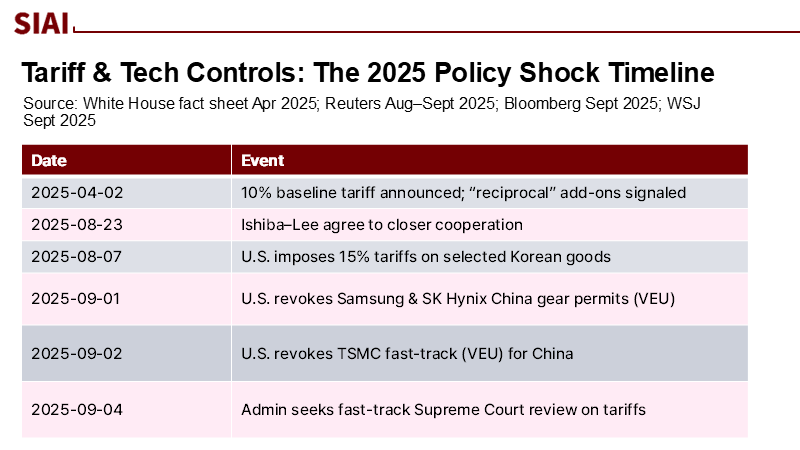

The key number in Northeast Asia this year is 10 percent—the import tax imposed by Washington in April, with potential reciprocal duties of up to 50 percent for countries with large deficits. This measure, currently facing legal scrutiny, has altered trade dynamics, exposing Tokyo and Seoul to tariff risks from their security ally and uncertainties regarding advanced chip exports. In this climate, Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba and South Korean President Lee Jae-myung are signaling a shift toward Beijing. This move would have been politically risky in the past. As the policy evolves, the 10 percent import tax serves as a bargaining tool, complicating the relationship between security and economics in the region and impacting educational and innovation systems.

The unlikely convergence

What makes the current thaw between Tokyo and Seoul distinctive is not the warmth but the logic behind it. In late August, the two leaders issued their first joint statement in 17 years, explicitly calling each other “partners” and pledging “future-oriented” cooperation. The symbolism was hard to miss: Lee made Tokyo his first major stop before Washington, and his Liberation Day remarks framed Japan as an indispensable neighbor. Ishiba, bruised by summer electoral setbacks and accusations at home that he is too soft on China, nonetheless took the bet that stabilizing ties with Seoul would reduce strategic isolation as Washington’s trade policy turned more transactional. The arithmetic favors coordination: if historical grievances can be bracketed, both countries can negotiate export-control carve-outs, align their tariff hedges, and avoid undercutting each other in U.S. talks. This is not ideological rapprochement; it is crisis management driven by the tariff meter and the fear of waiver revocations on the very technologies—lithography tools, specialty chemicals, and high-bandwidth memory—that anchor their growth strategies. The fragility is equally apparent. Ishiba’s standing is contested and may not endure, while Lee, despite an early mandate, will face domestic temptations to mobilize anti-Japan sentiment if growth wobbles. For now, the détente holds because the costs of failure—squeezed margins in the U.S. and operational drag in China—are higher than the political pain of compromise.

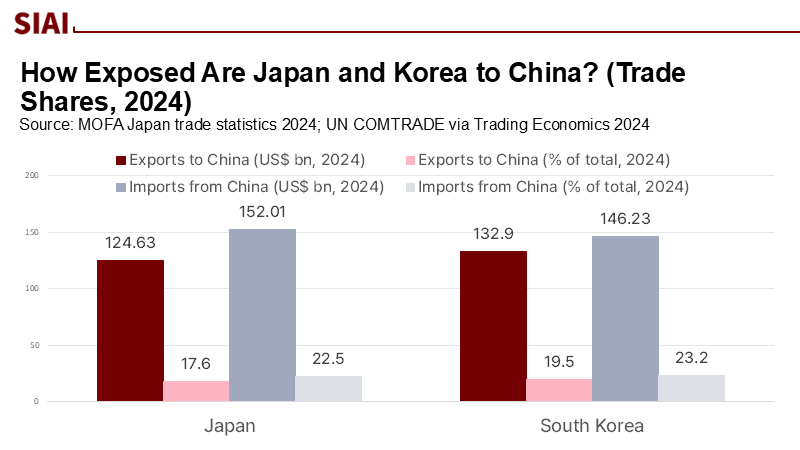

The more profound structural shift sits in the trade map. China remains a top partner for both economies. In 2024, it absorbed 17.6 percent of Japan’s exports and supplied 22.5 percent of its imports, while South Korea’s two-way trade with China hovered around $140 billion in imports and $125 billion in exports. When the United States universalizes tariffs—at least for the moment—Beijing gains leverage not by offering sudden concessions but simply by keeping market access stable. In that world, Tokyo and Seoul do not need to “tilt” toward China to hedge; they merely need to avoid needless shocks in the relationship. The revival of the China–Japan–Korea summit in 2024 was an early sign of this logic returning: leaders recommitted to people-to-people exchanges, science cooperation, and basic economic coordination, a floor under relations that can be activated when major-power policies become volatile. The near-term implication is sobriety: neither capital will abandon its U.S. alliance, but both will keep a second channel open to Beijing, if only to steady trade-sensitive sectors while tariff litigation plays out.

Beijing as an insurance policy

Semiconductors are where tariff policy and export controls directly touch university labs and corporate roadmaps. The United States has tightened licensing requirements for advanced chipmaking equipment in China. In early September, it began revoking or re-examining waivers that previously allowed leading firms to service or supply fabs based in China. Korean memory makers and Japanese equipment suppliers, though not identically exposed, face similar uncertainties: a revoked waiver can disrupt a toolchain, delay an upgrade cycle, and force costly workarounds—even if final production targets sit outside China. The message to Tokyo and Seoul is straightforward: align closely with Washington’s controls and negotiate case-by-case relief, or absorb deeper friction in Chinese operations. Beijing’s counter-leverage is subtler: maintain “constructive and stable” ties (relations that are mutually beneficial and not disruptive) and, in return, expect continuity of market access and fewer administrative ambushes. The calculus for Ishiba and Lee is therefore transactional rather than sentimental. They do not need strategic alignment with China; they need enough predictability to keep revenue-generating facilities running while they bargain for tariff relief in Washington.

Tariff shock is already showing up in Korea’s monthly prints. August exports missed forecasts, with a sharp drop to the U.S. market after new duties on sectors like autos, machinery, and steel, even as semiconductor shipments strengthened. Japan’s exposure differs in composition but is similar in vulnerability: specialty chemicals and high-precision components feed global tech supply chains, and even minor, temporary duties can disrupt just-in-time production. The political outcome is paradoxical. A left-leaning government in Seoul, historically inclined to underscore colonial grievances or to lean toward Beijing on some issues, now pivots toward pragmatic cooperation with Tokyo—not because the past has been solved, but because tariffs and controls penalize disunity. In Tokyo, an LDP leader accused by rivals of being “soft” on China nonetheless courts Beijing, where it lowers economic risk, even as he tries to keep deterrence with Washington intact. That cross-pressure is novel, and it explains why both governments are likely to meet more with Chinese counterparts in the coming months. Each new meeting reduces misunderstanding, but it also increases Washington’s anxiety that economic hedging could mature into strategic ambiguity.

The question that worries alliance managers is whether this hedging could escalate into outright balancing—Tokyo and Seoul teaming more closely with Beijing to extract concessions from Washington. The historical analogy often cited in Seoul is blunt: in 1981, after a military takeover, South Korea’s leader extracted face-saving diplomatic treatment from Washington by threatening alternatives. Today’s theater is trade, not tanks, but the bargaining template is recognizable. The credible threat is not to leave the alliance; it is to deepen economic engagement and coordination with China just enough to make U.S. tariffs and controls costlier to sustain. The more leaders and ministers meet, the more the scenario acquires plausibility—even if formal alignments do not shift. Whether that becomes a durable strategy depends less on the personalities of Ishiba or Lee than on the durability of the U.S. tariff regime and the pace of waiver decisions on critical technology flows.

What this means for campuses and ministries

Education is not a spectator in this reordering; it is one of the primary conduits through which shocks are absorbed. The United States hosted 1,126,690 international students in 2023/24, including 277,398 from China and roughly 43,149 from South Korea. Any U.S. policy swing that chills even a tenth of China-origin enrollments will ricochet through grant funding, lab staffing, and course offerings on both sides of the Pacific. Japanese and Korean universities can partly absorb that shock by recruiting students deterred by U.S. visa uncertainty through targeted scholarships, English-medium master’s tracks, and dual-supervision PhDs—particularly in semiconductor engineering, data science, and materials. Ministries should adjust scholarship rules, visa categories, and campus housing permits to streamline these processes administratively. The design principle is simple: treat inbound students as components of the talent supply chain for strategic industries, and align selection with national R&D priorities. Done well, education policy becomes an industrial policy with a human face—one that does not trigger export-control alarms but still feeds the skills pipeline.

The rules of collaboration will also need to be updated. Export-control tightening will spill into university–industry labs where equipment, datasets, or software might cross the line into controlled categories. Legal teams should assume that license decisions may lag, and that regulations could change mid-grant. There are practical hedges available now: structure cross-border projects so that controlled activities have domestic redundancy; register lab inventories and code with a shared compliance database that flags export-controlled items; negotiate “safe harbor” clauses in industry contracts that allow milestone extensions when license delays occur. The revival of trilateral dialogues with China matters in this context not for symbolism. Still, for hygiene: clear understandings about data governance and research ethics in low-security domains—such as public health, climate modeling, and materials science—reduce the risk that a compliance scare shuts down a broad program. Universities, in other words, can be the ballast in a gusty policy sea.

K–12 and vocational systems will feel the reordering as firms accelerate friend-shoring. If tariffs persist into 2026, companies will demand technicians and mid-career retraining at higher volumes. Korea’s semiconductor schools and Japan’s polytechnics should plan accelerated cohorts with embedded English and compliance modules, preparing graduates for a world in which export rules and data localization are part of the job. Ministries can seed this initiative with modular micro-credentials co-designed by firms and universities, which can be stacked into degrees. The metric of success is not only graduate placement but time-to-clearance for working on controlled equipment—a new bottleneck in the talent pipeline that is visible today in delayed fab upgrades when licensing slows. The public narrative should be frank: the tariff shock is a tax on complacency, and the only durable rebate is capacity.

The counterargument is that very little here is truly new: economic interdependence has long nudged Tokyo and Seoul toward pragmatic coordination whenever Washington’s attention wandered. There is some truth in that observation, and the 2024 revival of the trilateral summit underscored a broader desire to stabilize relations. Two features do distinguish today’s landscape, however. First, tariff policy has been universalized—at least in design—pulling friends and competitors into the same emergency framework. That raises the cost of misalignment even among allies, and explains why Japan and South Korea are less tolerant of bilateral friction than in previous cycles. Second, the chip-controls regime has crept from blocklists into operational chokepoints: waiver revocations now directly affect factory toolchains, and firms must adapt in weeks, not quarters. Together, these features give Beijing leverage without demanding overt concessions; the mere promise of smooth market access becomes a tradable commodity. That is why it is plausible, as critics worry, that Tokyo and Seoul will meet more with Beijing—not to abandon Washington, but to price in a second source of stability when U.S. policy is volatile. The United States may not like the optics, but the alternative is supply-chain whiplash that harms everyone.

One critique is that security always trumps economics in Northeast Asia and that Washington’s alliance architecture can readily discipline tariff blowback. The rejoinder is empirical: August’s Korean export data already reflect tariff-induced strain in sectors outside semiconductors, and Japanese firms are signaling contingency planning for specialty inputs if licensing remains tight. Another critique is that Ishiba’s tenure is too frail to matter. That misreads the mechanism: the policy signal to Beijing and Seoul is not personal; it is structural. Even if leadership changes in Tokyo, the incentives created by a universal tariff and contested export-control waivers will remain until the courts or Congress rewrite the rules. The default policy for U.S. allies is therefore hedging: locking in the alliance for security and opening a second channel for economic stability. For educators and administrators, this means building redundancy in student pipelines, co-funding trilateral research in low-security domains, and training a generation that is fluent in both export law and experimental methods.

The 10% number will not by itself decide East Asia’s future. However, it has already forced previously avoidable choices: whether to absorb economic pain to signal loyalty or to seek stability through a cautious, technocratic approach to Beijing. Japan and South Korea appear to be choosing a third path—hold the U.S. alliance, lower the temperature with China, and cooperate to manage risk. That formula is uncomfortable for ideologues but pragmatic for economies built on precision manufacturing and knowledge flows. For universities and ministries, the call to action is clear. Build parallel on-ramps for talent when U.S. policy is uncertain; hard-wire compliance into research design; treat exchange programs not as amenities but as components of industrial strategy. If the courts pare back emergency tariff authority this autumn, the immediate pressure may ease. Yet the lesson will remain: when trade is weaponized, education and innovation are collateral—and, paradoxically, the best defenses. The way to navigate the narrow channel is not by choosing a side but by investing in the systems that keep learning, research, and supply chains moving when politics lurch.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bloomberg. (2025, Sept. 2 & 4). U.S. pulls TSMC’s waiver for China shipments of chip supplies; Trump axing ‘Biden-era’ waivers in China rattles chipmakers.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Aug. 31). Ishiba’s China policy increasingly contested after electoral setback.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Sept. 1). Japan–South Korea diplomatic breakthrough remains fragile despite promises.

IIE (Institute of International Education). (2024, Nov. 18). United States hosts more than 1.1 million international students at higher education institutions, reaching all-time high.

Japan MOFA. (2024). China’s share of Japan’s total exports and imports (2024) [PDF].

Japan MOFA. (2024, May 27 & 2025, Aug. 23). Joint Declaration of the Ninth ROK-Japan-China Trilateral Summit; Japan–ROK Summit Meeting (Tokyo).

Korea Herald. (2025, Aug. 24). Lee, Ishiba vow future-oriented ties in 1st joint statement in 17 years.

Reuters. (2025, Aug. 23). Japan’s Ishiba, South Korea’s Lee agree closer cooperation before Lee meets Trump.

Reuters. (2025, Sept. 1). South Korea August exports miss forecast as U.S. tariffs weigh.

SCOTUSblog. (2025, Sept. 4). Trump administration urges Supreme Court to take up tariffs case.

Trading Economics (UN COMTRADE). (2025). Japan exports to China (2024); South Korea imports from China (2024).

Washington Post. (2025, Sept. 4). Trump officials ask Supreme Court to quickly allow sweeping tariffs.

Wall Street Journal. (2025, Sept. 4). Trump Administration seeks swift Supreme Court review on tariffs.

Comment