When Fame Becomes a Terms-of-Service: Why Schools Should Treat Fan Economies as a Safety Risk, Not a Sideshow

Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

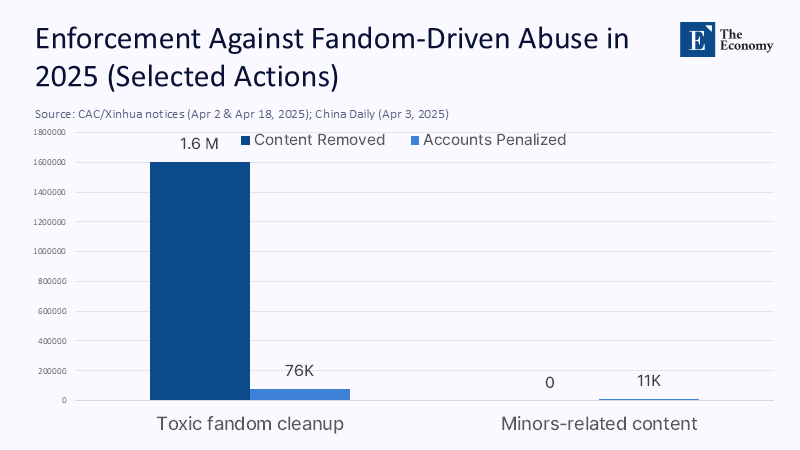

The most critical number in online culture right now is not a follower count; it’s 1.108 billion—China’s internet users as of December 2024—with 99.3% using social networks and 96.6% consuming online video, including short-form clips that supercharge parasocial intimacy. The scale of this issue turns whispers into weather, and weather into storms. In 2025 crackdowns, authorities said they penalized roughly 76,000 fandom-related accounts and permanently shut 3,767—an industrial quantity of rumor and mobilization masquerading as “community.” Meanwhile, deepfake abuse is no longer fringe: images of a world-famous singer spread to tens of millions of views within hours in January 2024, and threat-intelligence firms report a steep rise in malicious synthetic media. Put plainly: when attention is coin of the realm, unregulated fan economies mint mobs. Gender shapes who pays the highest price, but the root cause is structural—platform incentives, permissive “self-media” rules until recently, and management practices that monetize obsession. Educators can ignore this only if they believe students live offline. They don’t. Not anymore.

From Gendered Harm to Structural Hazard

The public question—“If you are famous, must you endure rumors, malicious attacks, and even being drafted into fan-fiction marriages?”—too often gets answered as if fame were informed consent. It isn’t. The deeper policy problem is a market design that rewards collective fixation and weaponizes intimacy. Fan cultures have always had extremes, but today’s hyper-scaled infrastructures turn a handful of “leaders” and gossip accounts into command-and-control systems: call-and-response brigades, rumor amplification, and coordinated boycotts. China’s regulators began dismantling the scaffolding in 2021, banning celebrity popularity rankings and curbing inducements for youth to buy votes in talent shows. Those measures were not merely moral hygiene; they were attempts to defuse structural hazards created by platforms and agencies that cultivate parasocial dependence. Structural hazard refers to the systemic risks and dangers that are inherent in the design and operation of a system or market. We should acknowledge gendered asymmetries—women, and feminized personas, often face sexualized abuse—but the fuse is the fanatic marketplace and the algorithms that feed it. That is the policy pivot: target the machinery, not just the manners.

What the Numbers Say—and What They Don’t

Start with reach. By December 2024, live-streaming users numbered about 833 million in China, and short-video users about 1.04 billion. Social networking? More than 1.1 billion. These are not audiences; they’re ecosystems in which parasocial bonds are formed hourly. Enforcement data show why scale matters: a 2025 campaign reported more than 1.6 million pieces of non-compliant fandom content removed and 3,767 accounts shut, while another notice cited roughly 76,000 accounts penalized across related actions. Add minors’ safety: In April 2025, authorities said over 11,000 accounts were punished for harmful content related to minors. And factor in synthetic media: a 2024 industry report flagged the rapid growth of malicious deepfakes; the Taylor Swift episode demonstrated how quickly non-consensual images can metastasize—over 45 million views before removal in one high-profile case. Even if platform data are imperfect and sometimes politicized, the direction is clear. A reasonable estimate, triangulating official user counts and enforcement posts, is that tens of millions of users routinely encounter rumor-driven campaigns yearly, with a smaller, far riskier subset involved in organized harassment. The precise denominator is uncertain, but the risk surface is not.

Method Notes: Where hard counts are absent, conservative lower bounds are applied. For example, with 96.6% of 1.108 billion users watching online video and 75.2% using live streaming, these are treated as distinct but overlapping risk zones for parasocial escalation. Narrative reports from state-affiliated outlets such as Global Times or China Daily are read as evidence of enforcement activity rather than as prevalence estimates. Deepfake risk is assessed by triangulating public incident metrics (view counts and time-to-removal) with independent industry studies instead of platform self-reporting. The approach prioritizes parsimony: establish a plausible floor of exposure while avoiding inflation of the problem.

Implications for Classrooms and Campuses

For an education sector that increasingly depends on streaming lectures, influencer partnerships, student creators, and school-run channels, fan economies are a safety issue, not a “culture” elective. The 2024 Regulations on the Protection of Minors in Cyberspace require schools and families to guide children toward rational, safe internet use; that’s not a poster on a hallway wall—it implies a codified duty of care. Practically, this means three shifts. First, digital-citizenship curricula must add parasocial literacy: what fan leaders do, how rumor cascades form, why “shipping” someone into a fake relationship is not harmless fun but a reputational hazard. Second, reporting mechanisms need to match the tempo of online harms; hours matter, not weeks. Third, policy must anticipate cross-border spillover. Korea’s anti-stalking law, strengthened in 2021, shows the value of criminalizing obsessive pursuit that has long plagued idol industries; its continued enforcement into 2024–2025 offers a model for schools hosting touring artists or collaborating with K-pop programs. Attention creates revenue for institutions, but it also creates targets; administrators should plan accordingly. Your role in this cannot be overstated. You have the power to make a difference, to protect your students, and to shape the future of digital education.

Reforming Platform Incentives Without Smothering Culture

It’s possible to curb abuse without strangling fandom. Three regulatory levers already exist and should be braided together. The first is algorithmic accountability: since March 2022, China’s algorithmic recommendation rules require transparency and guardrails for manipulative feeds; schools and cultural agencies should insist their vendors meet or exceed those standards, especially for campus apps and livestream platforms. The second is source authentication for synthetic media: deep-synthesis provisions effective January 2023 require labeling and other controls; procurement contracts should enforce them, with penalties when vendors fail to detect spoofed or sexualized fakes. The third is discretionary penalties calibrated to harm: new CAC penalty standards rolling out in 2025 establish tiers; institutions can mirror that logic in campus codes—escalating from content removal to bans and referrals to law enforcement. Crucially, these are structural fixes. By reducing inducements (ranking lists, pay-to-vote schemes), dampening “rage-bait” distribution, and making identity costs real for orchestrated harassment, we reshape the environment that fuels mobbing. This is a call to action, a roadmap for change, and a beacon of hope for a safer digital future.

Answering the Counterarguments

Three critiques recur. First, “Celebrities profit from attention; rough talk is the price of fame.” That assumes all attention is equal. It isn’t. The law already distinguishes criticism from targeted harassment and defamation; China’s 2023 guidance on cyberviolence clarifies that robust critique is not criminal, but coordinated insults, doxxing, or sexualized fabrications can be. Education policy should follow that line: protect debate, penalize organized abuse. Second, “Crackdowns chill speech.” They can, which is why safeguards matter: transparent appeal rights, independent audits of takedowns, and anti-retaliation protections for whistleblowers. Algorithm rules and deep-synthesis labeling requirements offer procedural hooks for that due process. Third, “This is just a gender fight.” No—gender shapes how harm is delivered (sexualized threats and fake intimacy are disproportionately aimed at women and feminized personas). Still, the spark is structural: parasocial markets premised on always-on emotional labor. If we focus only on etiquette or individual resilience, we will continue to misdiagnose a market failure as a manners problem.

What Education Leaders Should Do Next

The policy posture should be neither laissez-faire nor moral panic. It should be design-first. For educators, that means adopting “parasocial-risk” audits for every official channel; stress-testing response times for rumor spikes; and offering staff and students clear playbooks for when they become subjects of mass attention, consensual or otherwise. For administrators, it means upgrading partnerships with platforms: requiring proactive detection of doxxing, brigading, and deepfakes, and making service levels enforceable. For policymakers, it means aligning minors’ protection rules with algorithm and deep-synthesis regimes—closing gaps that allow “self-media” operations to profit from sexualized rumor and fake relationships while claiming the mantle of community. The K-pop experience is instructive: only when the anti-stalking law caught up with venue reality did agencies begin to change how they manage fan logistics. China’s fan-culture rectification—banning rankings, penalizing inducement schemes—shows structural levers exist. Blend those lessons, and schools can keep the expressive good of fandom while draining its most toxic incentives.

Accountability Needs Architecture, Not Outrage

The opening statistic—1.108 billion people online, nearly all on social networks—tells us why this matters for education now. Rumor, fan-fiction pairings, malicious attacks, and synthetic porn are not edge cases; they are foreseeable byproducts of a market that trades in intimacy at scale. Gendered harms are real and demand attention, but if we stop there, we win awareness campaigns and lose policy. The fix is architectural: remove ranking and inducement mechanics that turn devotion into debt, require algorithmic and deep-synthesis transparency, and build fast, fair redress systems that schools can use at the speed of a trending tag. We don’t need a culture war to protect privacy and dignity. We need to treat fan economies like any other high-risk infrastructure: design for safety, monitor the load, and shut down bad actors before the bridge collapses. Fame is not consent. It never was. Policy should finally behave as if that’s true.

The original article was authored by Jiannan Luo, who holds a PhD from the School of Government and International Affairs at Durham University. The English version, titled "The gendered cost of China’s online accountability," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Allen & Gledhill. (2023). China seeks to regulate deep synthesis services and technology. Retrieved August 2025.

Cambridge University Press. (2025). Digital Fandoms and the 227 Incident: A Case of “Cancel Culture” with Chinese Characteristics. The China Quarterly. Retrieved August 2025.

China Daily (Hong Kong). (2025, April 2). Crackdown on ‘fandom’ intensified. Retrieved August 2025.

China Law Translate. (2023, September 27). Cyberviolence Regulations (explainer and translations). Retrieved August 2025.

CNNIC (China Internet Network Information Center). (2025, May). The 55th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development. Retrieved August 2025.

Freedom House. (2024). Freedom on the Net 2024: China. Retrieved August 2025.

Guardian, The. (2024, January 31). Inside the Taylor Swift deepfake scandal. Retrieved August 2025.

Haynes and Boone. (2023, Dec.). China Releases Regulation on the Protection of Children in Cyberspace. Retrieved August 2025.

JD Supra / Dacheng. (2025, July 22). China Monthly Data Protection Update: CAC Penalty Discretion Standards. Retrieved August 2025.

Library of Congress. (2023, April 25). China: Provisions on Deep Synthesis Technology Enter into Effect. Retrieved August 2025.

National Law Review. (2025, May 1). China launches “special campaign” to clear and rectify abuse of AI. Retrieved August 2025.

Reuters. (2021, August 6). Weibo pulls celebrity ranking list after state media criticism. Retrieved August 2025.

Sensity AI. (2024). The State of Deepfakes 2024. Retrieved August 2025.

South China Morning Post. (2021, August 30). NetEase joins Weibo and Tencent in removing celebrity ranking lists. Retrieved August 2025.

Wired. (2021, October 26). China targets extreme internet fandoms in a new crackdown. Retrieved August 2025.

Xinhua. (2025, April 18). Over 11,000 online accounts punished for illegal, harmful content related to minors. Retrieved August 2025.

Comment