Cheap Money, Dear Consequences: What Empires Teach Us About Education Budgets in a Weak-Dollar World

Input

Changed

U.S. interest costs now rival defense as policy courts a weaker dollar Education absorbs the shock via costlier bonds, pricier imports, and tighter endowments Use credit guarantees, tradables-indexed grants, Fed independence, and automatic income-based repayment

In 2024, the United States spent about $950 billion on net interest, surpassing national defense spending for the first time in modern history. This should prompt an urgent change in how we discuss fiscal choices and public priorities, especially regarding education. Since 2020, interest payments have nearly tripled and are expected to exceed $1 trillion this fiscal year. This rapid growth limits funding for teacher salaries, campus upkeep, research grants, and school construction projects that were delayed during the pandemic. When debt repayments take the largest share of revenue, everything else gets pushed aside. This concern isn't just theoretical; the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts that interest costs will keep hitting new highs through the 2030s. The math is harsh, especially since the dollar has dropped significantly this year as the Federal Reserve reduced rates under intense political pressure and trade tariffs drove up prices. The mix of high debt, cheap money policies, and a weaker currency can be seen in the histories of former great powers, and this lesson is especially relevant for education policy.

A familiar script, updated for 2025

This pattern is well understood. When large states take on too much debt at the end of a cycle, they often resort to financial repression: a strategy that involves lowering interest rates, weakening the currency, and hoping to reduce real debt burdens. Venice pioneered forced loans (the prestiti) and repeated debt consolidations (Monte Vecchio, then Monte Nuovo) to extend its obligations over time. Spain funded its imperial commitments through silver inflows until inflation and costly wars forced multiple payment suspensions in 1557, 1559, 1574, and 1596. While cheap money addressed immediate cash-flow issues, it diminished trust in the long run. Modern studies indicate that lenders continued to support Philip II because he had revenue and a reputation to protect; however, this model was fragile, with defaults being a regular occurrence rather than an exception. The key point is not that default is around the corner; it's that reliance on financial tricks increases as the political will for fiscal reform decreases, which in turn affects real economic choices, like funding for schools and universities.

The United States is the 2025 version of this story. The federal government has imposed new reciprocal tariffs—a 10% baseline on nearly all imports, with higher rates for certain trade partners—on a struggling economy already facing high structural deficits. These tariffs, which were initiated by Customs in early April, have sparked legal disputes over the administration's use of emergency powers. Despite the ongoing debates, this policy has already changed pricing and trade dynamics. Markets view the Fed's rate-cut rhetoric and institutional instability as indications that the dollar will remain dominant but increasingly challenged. The dollar's share of global reserves dropped to about 57.7% in Q1 2025, and the dollar has significantly lost value this year, with strategists predicting further pressure if rate cuts persist. None of this leads to an immediate crisis. However, it changes the funding environment for public and educational financing, where the costs of imports collide with a weaker currency and higher borrowing rates.

If we feel reassured by low inflation averages, we should look more closely. The headline CPI is hovering in the high 2s, but prices for tariff-sensitive goods are rising above the pre-2025 trend. Early academic assessments suggest a short-term price spike from this year's tariff package, particularly in areas like apparel and household goods—exactly what schools need for procurement and facilities. While central bankers debate whether tariffs are worsening inflation, a school district's budget officer can't question the price of imported lab equipment or computer carts. Historically, Venice's experiments demonstrate how administrative solutions can buy time, while Spain's reliance on silver reveals how shifts in relative prices can alter the winners and losers. In 2025, imported inputs are likely to increase costs, even if the overall CPI remains close to 3%. Educators work in a microeconomy where these cost increases matter, potentially impacting the resources available for students.

The education transmission: rates, prices, and endowments in the new cycle

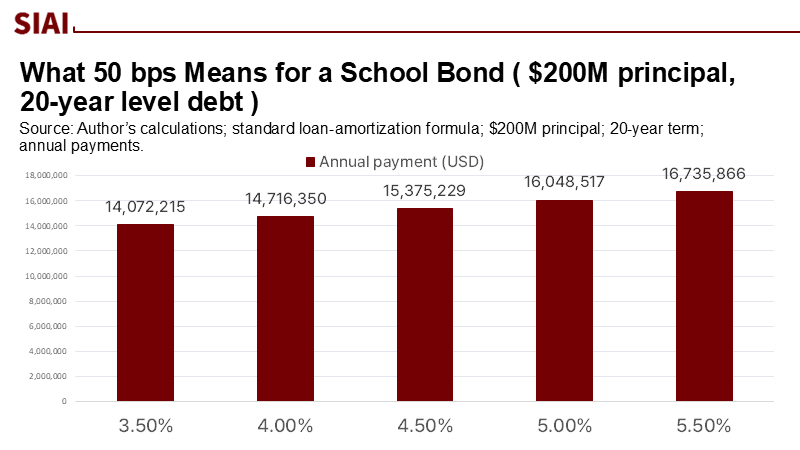

The borrowing channel is the most pressing issue. Municipal yields rose to multi-year highs in 2024 before easing, and long-term muni rates have climbed about 50 basis points more than comparable Treasuries this year. This steep increase has made capital investments more expensive just as federal pandemic aid is winding down. Districts have rushed to the bond market to cover deferred maintenance and safety upgrades; by June, school district borrowing was up over a third from the same time last year, nearing $45 billion. A rough calculation shows that a 50-basis-point rise on a new $200 million, 20-year school bond adds about $1 million in annual interest expenses. This often results in longer construction timelines or limits on technology upgrades. Universities are also seeing wider spreads, even for prestigious borrowers, with some top issuers paying significantly more than before the pandemic to obtain ten-year loans. The era of "free" capital is gone; the challenge has shifted from deciding whether to issue bonds to the strategic planning of what to cut to make it happen.

The price channel also plays a significant role. A weaker dollar and new tariffs impact education budgets through the cost of imported goods and materials, including microscopes, networking equipment, CNC machines for vocational programs, HVAC components for campus renovations, and even paper and uniforms. Early evidence indicates that prices for essential goods affected by tariffs are running nearly 2% above the pre-2025 trend, with considerable variation across categories. The Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates that overall inflation remains below peak pandemic levels. However, for procurement officers, the relevant figure is the delivered cost of specific items, not the CPI average. Suppose a district's $4 million lab renewal package has a 30% share of imports, and import prices increase by 5% in dollar terms. In that case, the project's price rises by about $60,000 before installation costs—a sum large enough to delay ordering critical spectrometers or defer an ADA compliance upgrade. Small percentage increases can become substantial budget issues when multiplied across 13,000 districts and 3,900 degree-granting institutions.

Households feel the financing channel directly. Federal student loan rates for undergraduates are determined each year by Treasury auction results; for 2025–26, the subsidized and unsubsidized rate is set at 6.39%, slightly lower than last year but still much higher than in the pre-2022 era. On a standard ten-year repayment for an average $27,000 undergraduate debt, that rate translates to a monthly payment in the low $300s. A 100-basis-point change can alter the monthly fee by about $12 to $15 through simple amortization, which is significant for families on tight budgets. The broader point is not just the exact amounts; it's that the overall economic situation influences the cost of attending college and repayment patterns, impacting enrollment for price-sensitive students. Ignoring this connection could be a grave mistake.

Endowments add complexity. The 2024 NACUBO-Commonfund study reported an average return of +11.2%—a welcome relief following the FY 2022 drop and lackluster FY 2023 results. However, the market structure is evolving. The "Swensen model," which favored private markets, is now facing squeezed profit margins and liquidity challenges. Between 2023 and 2024, average endowments lagged behind a simple stock-bond mix by about two percentage points in some analyses. Some funds are even considering selling private-equity shares at discounts. Despite strong FY 2024 returns stabilizing payout rates, a weak dollar, and slow private-market exits could renew tensions between funding current operations and maintaining purchasing power—especially if Congress increases taxes on endowment income. For institutions reliant on tuition, this financial pressure is immediate: rising borrowing costs, increasing prices for imported goods, and more unpredictable endowment withdrawals. At the same time, student demographics indicate flat enrollment growth over the next five years.

Policy that learns from history—before the bill falls due

If Venice and Spain provide warnings, they also offer solutions. Venice's forced-loan system was an early, albeit undemocratic, form of credit support; modern alternatives exist that are both fair and targeted. Recent U.S. studies indicate that state credit enhancement programs reduce borrowing costs for school districts by approximately 6% compared to non-enhanced debt, thereby helping to close the capital spending gap between wealthier and poorer neighborhoods. This is the most effective lever we have to counter macroeconomic trends affecting K-12 infrastructure, without relying on interest rate cuts or favorable currency shifts. This policy is budget-friendly and scalable: we can expand state-level guarantee programs where they are not currently in place, standardize them where they are, and connect them to maintenance backlogs and safety upgrades, rather than focusing solely on stadiums and luxury features. The historical comparison only matters to the extent that it prompts us to adopt proven methods that distinguish local school investments from national financial conditions.

Next, we should connect parts of federal and state education procurement to import-price realities rather than relying on CPI averages. When the dollar weakens and tariffs increase the costs of tradable goods, purchasing offices need flexibility to maintain program quality. A two-year, formula-driven "tradables top-up" could automatically adjust grant limits for research equipment, CTE tools, and special-education technology based on a trade-weighted import-price index, effectively phasing out when pressures diminish. This isn't an open-ended budget increase; it's a safety measure to ensure quality in items most affected by currency and tariff fluctuations. We already have a precedent for targeted stabilization—consider FEMA's post-hurricane cost-index adjustments—indicating that the necessary systems are in place.

Third, we should intentionally protect monetary institutions from short-term political influences. Markets are already showing doubt about the Federal Reserve's independence, and this skepticism affects the risk premium that borrowers in the education sector must pay. Expectations of rate cuts have helped to reduce the dollar's value by nearly 10% this year; this may lighten some debt service burdens in the short term, but it complicates procurement and suggests a vulnerability that raises costs elsewhere. In simpler terms, every challenge to central bank independence eventually appears in a school board budget. Congress may not be able to create confidence, but it can avoid undermining it.

Fourth, we should carefully balance operating and capital funding. In 2025, school districts are issuing bonds at the highest rate since before the pandemic as federal support dwindles. There's a temptation to direct capital expenses toward visible projects while neglecting operations. This strategy becomes risky when capital goods reliant on imports become pricier and when long-term debt locks in an unsustainable cost structure. A better approach is straightforward: pair capital funding with maintenance budgets; require accounting for costs throughout a project's lifecycle; and limit annual debt service to a percentage of local revenue to avoid the slow crowding out that repeatedly harmed Spain's Habsburg court. History reminds us what happens when we ignore cash-flow constraints.

Ultimately, we must prioritize students and families in discussions about financing. We have come to accept interest rate changes on federal student loans as if they were inevitable. They are not. They are policy decisions—decisions now influenced by a macroeconomic stance that accepts currency depreciation to manage public debt. If we follow this approach, we should also ensure automatic income-based repayment enrollment at the start of loans, provide portable emergency forbearance that does not capitalize interest, and offer clearer disclosures of total repayment costs under likely interest rate scenarios. A weaker dollar and more expensive debt create hardships for first-generation students balancing work, family, and school. The student who delays or gives up on earning a degree because of rising rates is not just a statistic; she represents our workforce problem in five years.

America spending more to manage old debt than on defense serves as both an indictment and a guide. We are not destined to repeat Venice's financial improvisations or Spain's defaults; we do not need to accept that a weaker dollar and falling rates will squeeze classrooms. We can implement modern versions of effective strategies: state credit enhancements to reduce school borrowing costs, import-price adjustments to maintain program quality, institutional safeguards to protect monetary policy, and student-oriented repayment options that mitigate interest rate volatility. Suppose Washington's macroeconomic strategy aims to reduce real debt burdens by tolerating a weaker currency and low nominal rates. In that case, education policy at the state level should work in opposition to this: to strengthen financial positions, expedite decision-making, and safeguard student learning resources from unstable market conditions. History warns us not that empires always collapse, but that financial obligations eventually come due. The call to action is simple: pay today—intelligently—so classrooms do not pay tomorrow.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Boston Fed. (2025). The impact of tariffs on inflation (Current Policy Perspectives).

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025). Consumer Price Index Summary (July 2025).

CBO. (2025a). The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035.

CBO. (2024b). Monthly Budget Review: September 2024.

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. (2024). Interest costs have nearly tripled since 2020.

Council on Foreign Relations. (2024). For the first time, the U.S. is spending more on debt interest than defense.

Drelichman, M., & Voth, H.-J. (2014). Lending to the Borrower from Hell. Princeton University Press. (Overview at UBC, 2014).

IMF. (2025). COFER: Currency composition of official foreign exchange reserves (Q1 2025 revision).

InvestmentNews. (2025). With Covid cash gone, public schools swarm muni bond market.

NACUBO–Commonfund. (2025). 2024 Study of Endowments: Key highlights.

Reuters. (2025a). U.S. customs begins collecting 10% baseline tariff (April 5, 2025).

Reuters. (2025b). What’s in Trump’s reciprocal tariff regime (April 3, 2025).

Reuters. (2025c). Dollar cedes ground in global reserves; dollar weakens in 2025.

Reuters. (2025d). Fed rate cuts and doubts over independence to keep dollar under pressure (Sept. 3, 2025).

StudentAid.gov (U.S. Dept. of Education). (2025). Interest rates for new Direct Loans, 2025–26.

St. Louis Fed (FRED). (2025). Nominal Broad U.S. Dollar Index (monthly).

Yale Budget Lab. (2025a). Where we stand: Fiscal and distributional effects of all U.S. tariffs enacted in 2025 (through April).

Yale Budget Lab. (2025b). Short-run effects of the 2025 tariffs so far.

Yang, L.-K. (2024/2023). School District Borrowing and Capital Spending. Education Finance and Policy; Brookings working paper version.

Historical context (Venice/Spain): Fratianni, M. (2006). Did Genoa and Venice kick a financial revolution? OeNB Working Paper 112.

Lane, F. C. (1966/1977). Money and banking in medieval and Renaissance Venice (with C. M. Cipolla). Overview excerpts via University of Chicago Press.

Comment