One Price, Two Cycles: Why the "Natural" Interest Rate Splits in Practice

Input

Changed

Business and financial cycles require different neutral interest rates East Asian data show the gaps are often large Policy must balance growth needs with financial stability

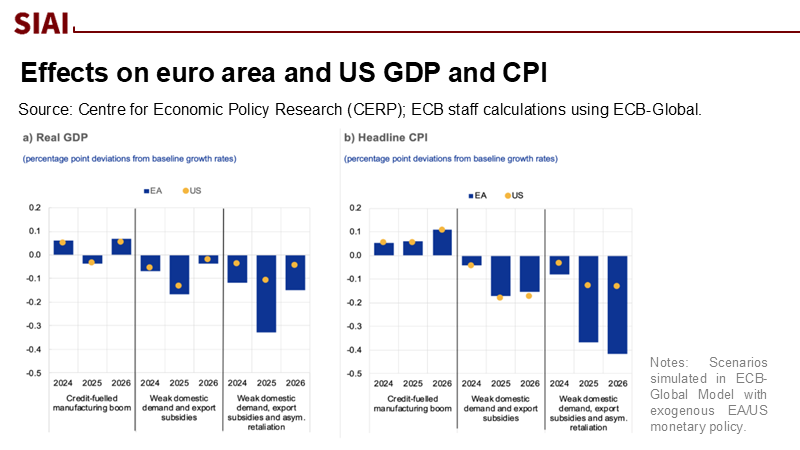

The most crucial number in monetary policy is not found in any printed material. It is the "natural" real interest rate that keeps the economy stable. However, the reality is far more complex and intellectually stimulating. There are at least two relevant rates at play in real time. Business cycles run typically between 2 and 5 years, while financial cycles, influenced by credit and property prices, span 10 to 20 years. This intricate interplay of cycles means that when central banks focus on stability based on the business cycle, they can easily disrupt the longer financial cycle, and vice versa. Recent evidence from East Asia shows that these two neutral rates do not always align, as policy that appears neutral for growth may seem too loose or too tight for financial stability, depending on our perspective. Treating money as a single "price" across markets is a neat theory that collapses under the weight of differing timeframes. This leads to a structural policy trade-off that cannot be ignored.

The illusion of a single price of money

Textbooks often portray a single real interest rate that balances interconnected markets. This is what we refer to as the 'illusion of a single price of money'. In reality, the neutral rate stabilizing output and inflation at business-cycle frequencies can differ from the rate addressing financial imbalances. New estimates for China, Japan, Korea, and the United States, using a frequency-domain approach, highlight this difference sharply: from 1996 to 2023, the stance implied by a business-cycle natural real interest rate (r*) often varies from that of a financial-cycle r*, with the United States being a partial exception. The method, which involves band spectrum regression with wide uncertainty bands, enables us to interpret the same data through two different lenses, sometimes flipping the perspective. What seems 'too loose' for the financial cycle can appear 'about right' for growth. This is not mere measurement error; it reflects the reality of two separate propagation mechanisms, namely the impact of interest rates on economic development and the influence of interest rates on financial stability.

The analytical basis for this distinction has been developing for a decade. The dynamics of credit and property prices move more slowly and in larger waves than GDP changes. Research from the European Central Bank showed how credit and housing cycles differ in length and turning points from output cycles. This means that stabilizing one can cause the other to misalign. Further studies have measured variations across countries in financial-cycle lengths, emphasizing why a single, static r* is a poor guide for open economies with deep mortgage markets. If monetary policy is set to the "average" cycle, it ultimately suits neither.

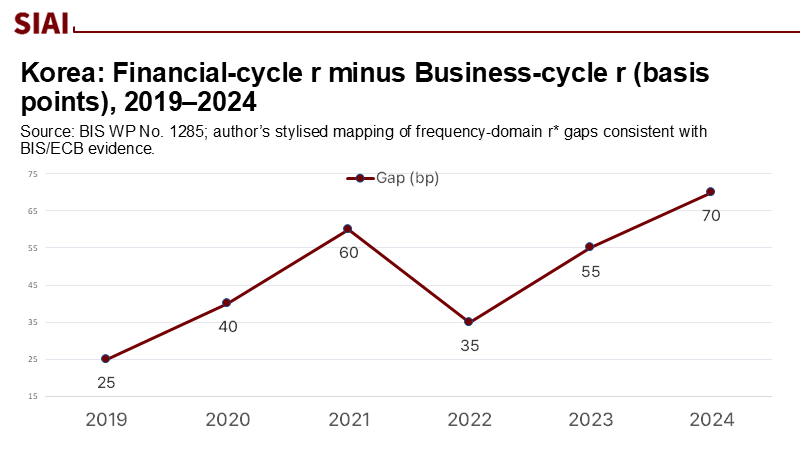

A policy rule that overlooks the longer cycle is not neutral; it is shortsighted. In the context of monetary policy, 'neutral' refers to a stance that neither stimulates nor restrains economic activity. Evidence from East Asia suggests that when assessing stance based on business-cycle r, monetary policy appears to be looser in Korea and the United States, but tighter in China and Japan. However, switching to the financial-cycle r changes that perspective and increases the range of uncertainty. The takeaway is not that the natural real interest rate is impossible to know; it is frequency-dependent and influenced by the current state. This underscores the need for clear dual-horizon assessments rather than relying on one unobservable figure. In other words, 'neutral' should be defined according to the specific objective and the timeframe in which risks accumulate. Clear communication of these assessments is crucial to ensure that all stakeholders understand the rationale behind the policy decisions.

Policy trade-offs under different real interest rates: lessons from East Asia

Consider a specific dilemma: rising housing prices occurring alongside sluggish growth. International forecasters have reduced Korea's growth outlook for 2025 to about 1%, citing tariff challenges, weak investment, and political uncertainty. Yet, housing prices in Seoul have increased year-on-year, even as many regions face declines, signaling localized demand despite broader economic stagnation. If the central bank cuts rates to align with the business-cycle real interest rate and stimulate activity, it risks fueling property price increases in the capital. Conversely, if it tightens to address the financial cycle, it may stifle an already fragile recovery. This divergence is not just a theoretical issue; it is a real-world challenge that underscores the pressing nature of the problem. This is a clear example of the policy trade-offs that can occur under different real interest rates, and it underscores the need for a more nuanced approach to monetary policy.

Japan illustrates a contrasting scenario over a more extended period. After years of extremely low rates and balance-sheet measures, cautious normalization began in 2024. Business-cycle indicators suggested marginal growth—close to zero—while some asset markets remained sensitive to global liquidity and exchange-rate fluctuations. Estimates of real interest rate in the frequency domain imply that Japan's stance appears tighter when viewed through the lens of the financial cycle rather than the business cycle. This highlights how even minor policy adjustments can significantly impact leverage dynamics, even if short-term output gaps are small. The lesson is clear: the same policy rate can affect the economy through two different channels in varying ways.

How should this influence decision-making? A practical approach is to tie short rates mainly to the business-cycle of expected inflation, where their effect on demand and inflation is most apparent, while employing macroprudential tools for the financial cycle. In Korea, this means combining rate relief with stricter loan-to-value and debt-service rules in overheated areas, along with measures to boost housing supply. This nuanced approach, which aligns with the authorities' actions as prices in Seoul have diverged from the national trend, emphasizes the importance of your role in shaping policy. It minimizes the risk of applying one blunt instrument for two different purposes and transitions "trade-off" into "policy mix." It's a recognition of the complexity of the issue and the need for a multifaceted solution.

From diagnosis to design: implementing a two-neutral approach

Operationally, a dual-neutral framework requires two dashboards. The first focuses on traditional cyclical indicators, including output gaps, wage growth, service inflation, and short-term inflation expectations. These guide the relationship between policy rates and the business cycle, as well as the natural real interest rate (r*). The second dashboard tracks slower-moving financial cycle indicators, including credit-to-GDP gaps, loan growth across segments, term premia, bank lending standards, and mortgage debt service ratios. These indicators correlate with the financial cycle r. The United States has strong financial condition indices that combine rates, spreads, equity valuations, and the dollar. A similar index, adjusted for local conditions, could effectively support the second dashboard in other economies. The goal is not to directly "target" the index but to assess whether the stance that is neutral for growth is inadvertently too loose for leverage.

Next is instrumentation. Macroprudential policy naturally aligns with financial-cycle r: this includes dynamic caps on loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios, countercyclical capital buffers, sectoral risk weights, and borrower-focused tools. Research from the BIS emphasizes how standard financial-condition measures coincide with—and occasionally amplify—policy cycles. This underscores the need for predefined macroprudential rules that tighten when credit and property cycles exceed set thresholds, even if the short rate is reduced to match the business-cycle r. Precise sequencing helps: first announce macroprudential tightening, then implement rate relief, showing that the two neutrals are being managed in unison rather than in opposition.

Ultimately, prioritize transparency and education. Publish both ranges for neutral rates along with uncertainty bands, and clarify which objective is most pressing. In a wage-price surge, the business-cycle of the natural real interest rate (r*) is the guiding factor; during a credit boom with stable inflation, the financial-cycle nominal interest rate is the limiting factor. Where precise numbers are lacking, provide explicit visual representations. For example, if near-term estimates place business-cycle r* at 0.5% real and financial-cycle r* at 1.5% real—a gap of 100 basis points—practical adjustments might involve a 50-basis-point cut in the policy rate (moving toward the business-cycle neutral) along with a corresponding tightening in borrower-based macroprudential measures (like lowering LTV ceilings in heated areas), calibrated using stress-testing. The key point here is straightforward: translate macroprudential adjustments into expected changes in credit growth and debt-service ratios, and connect those to shifts in default probabilities during downturns. The goal is not precision but discipline.

The straightforward idea of a single "price of money" served us well when financial cycles were less significant. In today's economy, long-term cycles are just as crucial. Viewing the neutral rate as frequency-dependent does not complicate policy; it clarifies it. We need to stop questioning whether policy is above or below r* and start asking which r* we are considering—the one stabilizing demand over the next two to five years or the one controlling the ten-to-twenty-year leverage cycle. Evidence from East Asia indicates that these pathways often diverge significantly. Ignoring this complexity can lead to weaker growth now or sharper financial adjustments later. A two-neutral framework, with macroprudential policy sharing the responsibility, represents a clear improvement. We need to define our objectives, disclose the ranges, and sequence our tools. Neutrality is not just a number; it is a choice that depends on the timeframe. The sooner we acknowledge this, the fewer avoidable errors we will make.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Ajello, A. et al. (2023). "A New Index to Measure U.S. Financial Conditions." FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Bank for International Settlements (2025). Annual Report 2025: Financial conditions in a changing global financial system (Ch. II). BIS.

Global Property Guide (2025). "South Korea—Price history."

OECD (2025). Economic Outlook, Volume 2025 Issue 1: Korea. OECD.

Rünstler, G. (2016). "How distinct are financial cycles from business cycles?" ECB Research Bulletin.

Schüler, Y. S. (2020). "Financial cycles: Characterisation and real-time measurement." Journal of International Money and Finance.

Siklos, P. L., Xia, D., & Chen, H. (2025). "R* in East Asia: business, financial cycles, and spillovers." BIS Working Paper No. 1285.

Swiss Embassy (SECO) (2025). Economic Report 2025: Japan. Government of Switzerland.