Proposing an Education Agenda for Democratic Resilience: when Facts Don’t Move Votes

Input

Changed

Confidence follows identity more than facts Schools should teach election procedures and prebunk manipulation Local transparency and routine audits build resilience when results disappoint

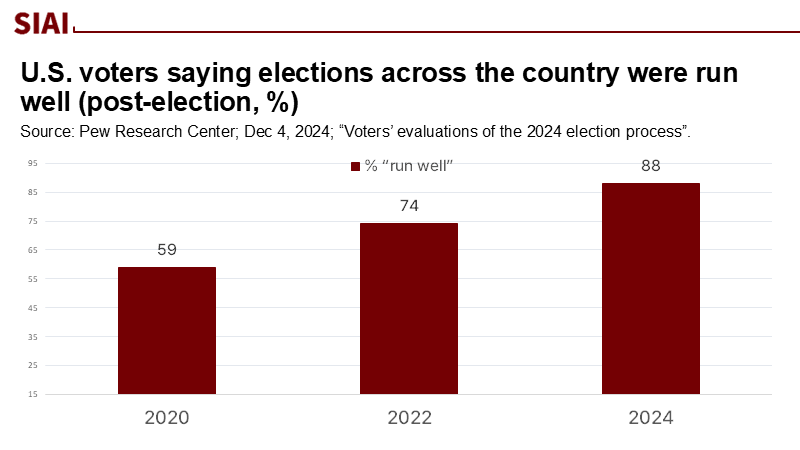

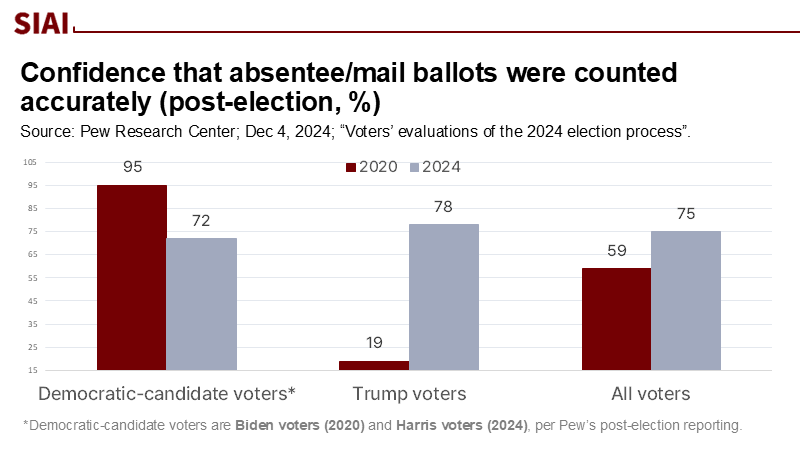

The most telling number from the last election cycle isn’t a turnout figure or a swing-state margin; it is seventy-two. This is the percentage of Trump voters in 2024 who feel confident that absentee and mail ballots were counted correctly. This is a significant increase from just 19% among the same group after 2020. The rules for processing mailed ballots didn’t change a lot. What changed was who won. This shift reveals an uncomfortable truth: for many citizens, confidence is more about identity and outcomes than it is about facts. If accurate information alone shaped beliefs, we would debate how to audit results, not whether counting happened at all. Instead, educators and election officials operate in a world where a clear victory can ease doubts overnight, while a loss can spark them. Narratives spread faster than corrections. Civic education, therefore, plays a crucial role in not only clarifying facts but also fostering civic resilience that persists even when people disagree with the outcome, empowering citizens to make informed decisions.

Across democracies, the pattern is similar. In the United States, Congress certified the 2024 presidential result without any objections, and the transition followed normal constitutional channels. This marked a shift after the chaos of 2021. In Brazil, however, prosecutors claim the outgoing president tried to hold onto power after losing, and the courts are currently weighing those actions. In South Korea, a constitutional crisis reached its peak with the removal of a president following a brief declaration of martial law, which led to a snap election. These events highlight not just “misinformation” but also the clash of partisan identity, institutional strength, and public trust. Education systems must work at that intersection, where identity can overshadow explanation, because that is where citizens learn the judgment skills they will bring to the voting booth.

Why Facts Alone Keep Failing

Last year was labeled the first primary “AI election.” Many feared an overwhelming amount of synthetic falsehoods would mislead voters. That risk is real and growing, but post-election accounts suggest the impact was mixed. A few high-profile deepfakes caught attention, while much of the persuasion relied on older tactics—rumors, selective framing, out-of-context videos, and repetition. This doesn’t mean we can let our guard down. Even with limited deepfake numbers, this technology enhances the “liar’s dividend.” It allows bad actors to dismiss genuine evidence as fake and casts doubt on any inconvenient information. However, schools play a crucial role in reducing the impact of such misinformation. By educating students about manipulation tactics and how trustworthy information is produced and verified in their own communities, schools can instill a sense of reassurance and confidence in the next generation.

On the evidence side, short, clear explanations of how ballots are verified and counted can help reduce misunderstandings, according to experiments. “Prebunking” videos—brief lessons that illustrate manipulation tactics like scapegoating or false dilemmas—also show small but lasting gains in recognizing misleading content in tests with millions of views. However, lab success doesn’t always translate to the chaos of real campaigns. The effectiveness of these efforts depends on timing, the credibility of messengers, and whether the messages relate to local procedures that people can observe. Therefore, educational interventions must be designed with these factors in mind: early, repeated, and grounded in local practice, not abstract civic principles.

Trust patterns support this idea. Before South Korea’s 2025 crisis, public trust in national institutions was lower than in local ones. In the United States, confidence in election administration rose after 2024, but mainly because the winning coalition felt reassured. These changes remind us that the amount of information matters, but so do identity and institutional context. Education may not change who wins elections. However, it can make the mechanics of elections familiar, visible, and reliably predictable, making them less susceptible to revision by the loudest voices online the day after the election. This underscores the need for a firm commitment from schools and policymakers to implement these strategies, as their roles are crucial in shaping the future of democratic stability.

From “Debunk” to “Design”: Introducing a New Playbook for Schools

First, transition from teaching civics as content to civic practice. Every upper-secondary class should complete an “election integrity lab” related to their local area. Students would track the chain of custody for test ballots, observe logic and accuracy testing on machines, talk to poll workers about provisional votes, and write clear public explanations about each step. The goal is not propaganda; it is to promote familiarity. Research in election administration shows that simple, procedural messages from trusted officials—like what audits are, when they happen, and how discrepancies are addressed—can help reduce the spread of rumors. When students help create and share these messages, they internalize the process and become credible local sources for families who may not have the time to read a white paper.

Second, institutionalize prebunking. Schools can provide three brief “micro-lessons” each term—one on manipulation tactics in political ads, one on understanding how a viral rumor spreads, and one on the liar’s dividend. The evidence shows modest yet meaningful promise: randomized trials demonstrate small to medium effects in recognizing manipulation that last for weeks, and broader analyses of media literacy interventions reveal reductions in the willingness to share false information. Method note: if we assume a conservative effect size of 0.15–0.20 standard deviations in manipulation recognition from short prebunking lessons, a group of 400 students could see about 30–40 more students shift from “at risk” to “resistant” categories on validated recognition scales. This isn’t a magical solution, but in a close race, it could mean fewer households spreading the next viral falsehood.

Third, evaluate what we teach. Replace quizzes on constitutional trivia with scenario-based assessments under time pressure. Students must assess a hypothetical viral claim about their county’s ballot curing process using official documents and, if necessary, a phone call to the elections office. Rubrics would score sourcing, reasoning, and communication. Teacher professional development should change accordingly; even a one-day training can alter classroom practices if it is practical and tied to usable materials. Pair this with district-level “integrity dashboards” that compile student explainers, link to local audits, and feature prebunk clips recorded with election staff. Since these dashboards are local, they can be revisited every election cycle without needing extensive rewrites, serving as a reliable resource when new rumors arise.

Finally, teach students to think about proportionality. The World Economic Forum labeled AI-driven misinformation as a top short-term global risk, and that warning is valid. However, several year-end reviews argued that AI’s direct impact on election outcomes was less dire than feared, while polarization and attention dynamics were the main drivers of distortion. Students should learn to differentiate between the headline risks (notable deepfakes) and everyday risks (false framing, rumor recycling), as the countermeasures differ. The first requires technical understanding and knowledge of platform policies; the second requires habits of verification, patience, and an awareness of how institutions create trustworthy information.

Accountability Without Collapse

The experiences of three countries since 2022 highlight both the dangers of misinformation and the value of constitutional safeguards. In the United States, the 2024 result was certified without any challenges, marking a clear shift from the chaos of 2021. Surveys conducted after the election showed increased trust in the processes behind it, especially among the winners. In Brazil, prosecutors claim the losing incumbent explored extreme measures to disrupt the transition, and the courts are currently considering those actions. Meanwhile, in South Korea, a last-minute declaration of martial law failed, resulting in impeachment and a court-ordered removal. These events are not identical, but collectively, they illustrate an essential civics lesson: democratic institutions can bend without breaking when oversight is honest and transparent, and when consequences for anti-democratic behavior are enforced. This is a lesson schools can teach using primary documents, not slogans.

What does this mean for classrooms and districts? Treat accountability cases as case studies rather than morality plays. Students can explore how prosecutors secure evidence trails, how courts evaluate emergency powers, and how election agencies communicate during times of crisis. Districts should also conduct nonpartisan “civic readiness drills” each fall of a national election year: one homeroom period devoted to finding official information, reporting intimidation or misinformation to the proper authority, and understanding what audits reveal—and what they do not. These drills should be as routine as fire drills and free from partisan influence. Because the procedures do not change much each year, the same drill package can be reused, improved, and localized.

Skeptics may argue that media literacy is soft power in a complex world, and that polarization—not education—fuels belief. There is some truth to this. The 72% figure among 2024 Republican voters illustrates how identity can influence perceptions of the same process. But fatalism overlooks two critical realities. First, transparent and timely processes for messages from local officials can decrease the spread of rumors in the field. Second, lessons designed to prevent manipulation can improve recognition across political views in large-scale trials. Education won’t make campaigns gentle or social media feeds quieter. However, it can enhance the overall skills of the next electorate so that fewer people are caught off guard by the tactics used against them. This is a practical goal that administrators can plan for and policymakers can fund.

A final point concerns what we ask students to notice. In 2024, many expected AI to dominate the election narrative. Post-election reviews present a more complex picture: AI-generated content was present and sometimes misleading, but partisan cues and incentives for attention did most of the heavy lifting. This is strangely encouraging. We can teach students to identify familiar rhetorical tactics, verify claims against public records, and appreciate routine institutional work—such as canvassing, audits, and certification—that doesn’t grab headlines but holds the system together. Democracies are maintained not by viral clarity but by thousands of small, repeated acts of competence. Schools can model these actions regularly, on a termly basis.

Return to that number—seventy-two. It didn’t rise because clever fact-checks finally gained traction; it grew because a coalition succeeded. That is the starting point for education. The aim isn’t to force agreement or “fix” polarization through authority. It is to ensure that in the next tough period, more citizens understand how ballots are secured, where audits take place, and how to recognize manipulation when it’s happening. Incorporate election integrity labs into upper-secondary curricula. Prebunk early and briefly, each term. Assess under time constraints. Equip teachers with the tools to guide students through real procedures in their own counties. Fund local dashboards so that when rumors arise, communities can access trustworthy explanations already created by their schools. If we take these steps now, the next time identity threatens to overshadow evidence, more voters will know how to pause, check the process, and support the result—even when their side loses.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2024, November 6). Trump wins the White House in political comeback.

AP News. (2025, January 6). Congress certifies Trump’s 2024 win, without the Jan. 6 mob violence of four years ago.

Brennan Center for Justice. (2024, January 23). Deepfakes, elections, and shrinking the liar’s dividend.

Cambridge University & Jigsaw. (2022). Social media experiment reveals potential to “inoculate” against misinformation.

Edelman. (2025). 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report.

Financial Times. (2025, September 2). Jair Bolsonaro’s trial nears close as U.S.–Brazil relations plummet.

Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center. (2024, December 4). The apocalypse that wasn’t: AI was everywhere in 2024’s elections—but deepfakes and misinformation were only part of the picture.

MIT Election Data & Science Lab. (2024, February 28). Combatting misinformation and building trust in elections (Trusted Info).

OECD. (2024). OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions—Korea country note.

OPB/NPR. (2022, October 22). Why false claims about Brazil’s election are spreading in far-right U.S. circles.

Pew Research Center. (2024, October 24). Views of 2024 election administration and confidence in vote counts.

Pew Research Center. (2024, December 6). Striking findings from 2024.

Reuters. (2025, April 5). South Korea’s Yoon removed from office over martial law; election looms.

Roozenbeek, J., et al. (2022). Psychological inoculation improves resilience against misinformation at scale. Science Advances.

WIRED. (2024, December 2024). The year of the AI election wasn’t quite what everyone expected.

Comment