When Algorithms Wobble: AI, Information Cascades, and the New Bank-Run Curriculum

Published

Modified

AI accelerates information cascades, turning rumors into rapid bank runs Stability now hinges on dampening synchronized behavior, not just capital buffers Build rumor-aware stress tests, fast disclosures, and drill-based curricula

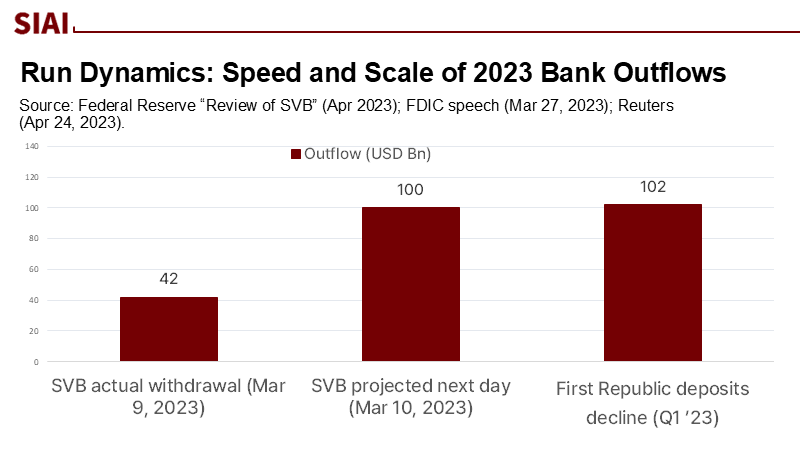

The systemic risk issue is not just a concern for supervisors and traders, but also for educators and administrators. This was starkly illustrated when forty-two billion dollars left a single U.S. bank in one trading day last year, with another $100 billion set to go the next morning. This is not a typo; it reflects the new speed of panic. In March 2023, depositors at Silicon Valley Bank withdrew a quarter of the bank's deposits within hours. Management expected more than half of the remaining balance would leave the following day. The bank failed before the line could finish forming. This episode reminded us that modern finance depends on coordination. When many people act together, even a well-built structure can fail. It also highlighted that social media and mobile banking have shortened the time between rumor and collapse. As generative AI speeds up how provocative claims are created, spread, and accepted, the coordination issue at the heart of financial stability becomes an information-systems problem. Educators and administrators play a crucial role in addressing this challenge.

We often use plumbing metaphors to explain systemic risk, such as liquidity pools, transmission channels, and circuit breakers. While those metaphors are helpful, they overlook the role of shared beliefs. When everyone sees the same information and reacts similarly, small shocks can amplify. The reason for action is not just balance-sheet math; it also involves real-time narrative dynamics. By 2025, those dynamics are managed through models—ranking, recommending, summarizing, and increasingly deciding. If the next crisis moves at the speed of content, then classrooms, newsrooms, compliance desks, and central bank dashboards are all part of the same early-warning system.

A well-known engineering story illustrates this concept. On the morning London opened its Millennium Bridge, it wobbled not because of poor construction but because people adjusted their steps in sync as the deck swayed. Each person's slight movement made it more likely the next person would adapt too. After reaching a certain point, the crowd and the bridge created a feedback loop. Engineers fixed the issue by adding dampers, not by retraining pedestrians. Finance has similar thresholds and feedback. While dampers exist—like deposit insurance, lender-of-last-resort, and stress tests—the crowd's rhythm has changed.

From Wobbly Bridges to Wobbly Balance Sheets

The bridge analogy highlights two truths about coordination. First, vulnerability can exist even when design standards are met. Second, thresholds are significant. With enough walkers, or similarly positioned investors, the system can tip into a different state. The Diamond-Dybvig theory formalized this in banking: multiple equilibria allow for a self-fulfilling run to happen even when fundamentals are solid. In the 2023 run episodes, the change was not just due to interest-rate risk on bank balance sheets; it was also a result of the density and speed of shared information that led depositors to the same conclusion simultaneously. This is why uninsured concentrations were so critical: at year-end 2022, about 88 to 94 percent of SVB's deposits exceeded the insurance limit, and those accounts could—and did—move together in large amounts.

Speed is now crucial. The Federal Reserve's review recorded more than $40 billion leaving on March 9 alone, with over $100 billion expected on March 10 if conditions did not change. This is much faster than traditional cases. First Republic then revealed over $100 billion in quarterly outflows, with an estimated $25 to $40 billion departing in single days during peak stress. Coordinated messaging among concentrated depositor networks clearly played a role. This is what the bridge taught us: small, rational individual actions, synchronized by feedback, create forces the structure wasn't built to withstand. Dampers must evolve as well.

AI Turns Rumors into Runs

Two developments since 2023 have strengthened the connection between rumor and withdrawal. The first is empirical: social media activity is associated with increased distress. A multi-author study using extensive Twitter (X) data shows that banks with higher pre-existing exposure on social media experienced larger losses during the run, even when controlling for uninsured deposits and unrealized bond losses. In hourly data, tweet volume about specific banks aligns with stock-price declines, indicating that attention itself amplifies vulnerability. The second is structural: AI changes how attention is produced. It reduces the cost of creating plausible claims at scale and increases the likelihood that many users will simultaneously see and act on the same narrative.

Caution is warranted in interpreting the figures. We now have early signs on the deposit side, not just prices. A UK study, reported in February 2025, indicated that AI-generated fake content about a bank's health notably increased respondents' intentions to transfer funds to the bank. The researchers estimated that, in some cases, a £10 social ad spend could influence up to £1 million in deposits. These figures, however, depend on context and design. Suppose a small budget can create a widely shared clip that trends for an hour. In that case, a local bank with a concentrated corporate clientele may face large synchronized outflows, forcing emergency liquidity measures. A simple calculation illustrates this: for a mid-size bank with $12 billion in deposits and 50 percent uninsured, a 2 percent shift among uninsured accounts equals $120 million. This is enough to trigger negative headlines, collateral haircuts, and more withdrawals. The narrative can drive causal connections.

Supervisors have taken notice. The BIS's 2024 Annual Economic Report warns that AI can both improve and threaten financial stability—enhancing monitoring while raising the risk that multiple actors take similar actions or act on shared model errors. The Financial Stability Board's 2024 assessment also highlights the concentration in standard AI tools and data, new channels for misinformation, and the need to improve supervisory capabilities. In the UK, the Bank of England has discussed the inclusion of AI risks in its annual stress tests and emphasized the need for governance that accounts for interactions among models. The trend is clear. We are transitioning from unique risks to system-level similarity risks—what engineers refer to as modes of vibration.

A reasonable critique counters that digitalization alone does not cause deposit volatility in regular times. The ECB's recent paper finds that mobile app availability and regular online use don't raise outflow volatility across the euro area by themselves; social media amplification mainly matters in specific stress events. This nuance is crucial. It shows that the risk is not "technology" itself, but rather technology interacting with shared exposure (uninsured deposits), unclear news, and time-compressed coordination. In other words, the bridge does not wobble every day. It sways when many pedestrians adjust together near a threshold—and when there are no dampers to manage the sway.

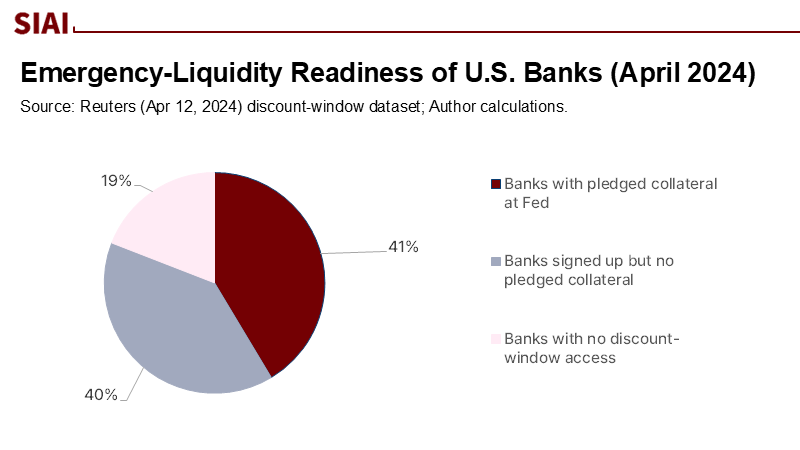

What We Teach Now Determines What Fails Next

If the coordination problem has shifted into the information landscape, the education agenda needs to adjust. Finance and public policy courses should include "information-cascade drills" alongside liquidity-coverage math. In practical terms, schools and training programs can run live simulations where students act as depositors, treasury teams, risk officers, journalists, and supervisors reacting to a sudden (synthetic) AI-generated rumor about a regional bank. The exercise should incorporate time-stamped social posts, changing search results, and models showing core funding loss linked to rumor intensity. It should also require decision-makers to rehearse emergency liquidity mechanics: positioning collateral, daylight overdraft use, and access to discount windows. One concerning data point: a year after SVB's collapse, less than half of U.S. banks and credit unions had established the legal authority to borrow from the Federal Reserve's discount window during emergencies—indicating a readiness gap now under consideration for reform. If graduates cannot execute these steps under pressure, their employers will struggle when every minute counts.

For supervisors and central banks, the lesson is to add dampers to the information system, not just the balance sheet. The policy discussions already reflect this direction. SUERF authors have suggested that authorities build expertise in AI, establish "AI-to-AI links" to allow supervisory tools to analyze and react to model-driven activity in real-time, and create "triggered facilities" that activate when monitoring signals exceed certain thresholds. The FSB recommends closing data gaps on firms' AI usage, tracking concentration in models and providers, and considering misinformation risks in stability frameworks. Specifically, stress tests should integrate rumor-shock modules that combine deposit flight patterns with content-spreading dynamics. Communication protocols should require banks to publish rapid and verifiable dashboards—detailing liquidity coverage, collateral held at central banks, and deposit mix—alongside pre-approved messaging that can go out within minutes, not hours. These are dampers to counteract the narrative swings that now drive withdrawals.

The private sector also has its tasks. Treasury and communications teams should work together on early-warning signals from public feeds. This includes tracking unusually fast correlations between negative terms and the bank's name, spikes in short-horizon retweet networks, and sudden changes in search-query patterns. The evidence from Cookson et al. indicates that such attention measures contain information on an hourly basis during crises. Institutions must also learn how to respond to issues of content authenticity. While stronger provenance signals will help until watermarking and cryptographic verification become standard, it is critical to train staff to debunk quickly with relevant information. A brief method note can guide decisions: estimate your bank's one-hour runoff elasticity to a 1-sigma spike in social media attention based on past incidents; establish a "go-public" trigger that balances the risks of triggering panic against the benefits of preventing it. When that trigger activates, release easy-to-check metrics—such as available central bank capacity, cash on hand, and ratios of insured to uninsured deposits—along with links to third-party validation when possible.

Policymakers should anticipate objections. Someone might argue that rumor-aware stress tests are speculative. Another concern is that "AI-to-AI" supervisory tools may lead to excessive monitoring or moral hazards. A third might fear that this approach could stifle free speech. The correct response is not to suppress content; it is to build resilience against cascades. The ECB's findings support this: technology is not destiny. We can lower thresholds by diversifying deposit bases, capping correlated exposures, and proactively committing to transparent emergency liquidity access. We can add dampers by speeding up supervisory communications and practicing them publicly. We can also slow the most hazardous feedback loops, for example, by considering time-limited withdrawal controls on large, fast corporate transfers when a bank has high liquidity coverage at the central bank, paired with real-time disclosures and strict safeguards. Think of this as temporary control for a swaying bridge while the dampers take effect, not a permanent obstacle.

Educators have a crucial role in this redesign. The next generation of risk managers and policy analysts should be skilled in both cash-flow math and attention dynamics. A capstone course may require students to create a simple rumor-to-run model using publicly available data. They would estimate its parameters from past events (such as tweet volume, search trends, and price gaps) and then propose a communications and liquidity strategy, which would be tested in a timed simulation. The goal is not to produce a perfect forecast; it is to enable disciplined action under uncertainty. If schools offer this training, agencies will seek out graduates, and banks will adopt it. The result is a system that views information friction as a key component of financial plumbing rather than an afterthought added to press releases.

Return to that 24-hour window in March 2023: $42 billion out, and another $100 billion lined up. The noteworthy point is not just the amounts; it is the coordination. AI will not alter the human inclination to act in unison, but it will make synchronized actions easier to initiate, faster to spread, and more challenging to reverse. That is why the next generation of dampers cannot rely solely on capital and collateral. They must also include rapid, credible disclosures; rumor-aware stress design; and hands-on experience with information shocks—in classrooms, drills, and at the very desks where decisions will be made. If we recognize that the system now sways when narratives align, our goal is to lower the threshold of wobble and accelerate the dampers. We need to develop a curriculum that identifies cascading risks as key concerns and invest in supervisory tools that directly engage with models. We should welcome criticism, promote transparency, and practice through challenging situations. If we do this, the next time the crowd starts to move, the bridge will steady faster, and the line at the virtual teller will be shorter.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2024). Annual Economic Report 2024: Artificial intelligence and the economy—implications for central banks (Ch. III).

Bank of England (2024, June). Financial Stability Report.

Cookson, J. A., Fox, C., Gil-Bazo, J., Imbet, J. F., & Schiller, C. (2023). Social Media as a Bank Run Catalyst. FDIC Working Paper.

Diamond, D. W., & Dybvig, P. (1983). Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity. Journal of Political Economy, 91(3), 401–419. (Classic foundation).

European Central Bank (2025). Wildmann, N. Mind https://www.ecb.europa.eu.

Financial Stability Board (2024). The Financial Stability Implications of Artificial Intelligence. https://www.fsb.org.

Federal Reserve Board, Office of Inspector General (2023). Material Loss Review of Silicon Valley Bank.

Federal Reserve (2023, April). Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank.

FDIC (2023, Mar. 27). Recent Bank Failures and the Federal Regulatory Response (speech).

Reuters (2023, Apr. 24). First Republic Bank deposits tumble more than $100 billion.

Reuters (2025, Feb. 14). AI-generated content raises risks of more bank runs, UK study shows.

Strogatz, S. H., Abrams, D. M., McRobie, A., Eckhardt, B., & Ott, E. (2005). Crowd synchrony on the Millennium Bridge. Nature, 438, 43–44. (See news/summary coverage).

SUERF (2025, May 15). Danielsson, J. How central banks can meet the financial stability challenges arising from artificial intelligence.

The Structural Engineer (2001). Dallard, P., et al. The London Millennium Footbridge (description of synchronous lateral excitation).

Comment