Tariffs, Talent, and the Stack We Teach: How U.S. Protectionism Is Rewiring Asian Education

Published

Modified

U.S. protectionism is splitting markets and learning tools into rival stacks China’s AI capex and ASEAN infrastructure create a pull toward its stack Answer with block-biliteracy, pooled compute, and portable standards to keep choice

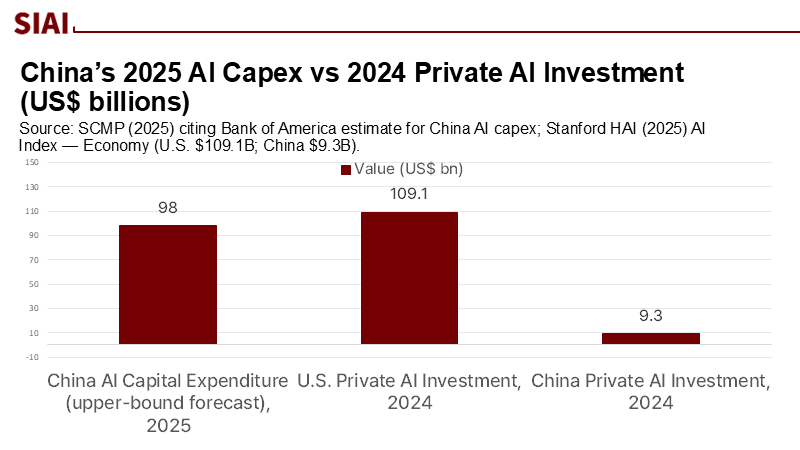

One number captures the urgency of the situation: 15%. This is the tariff level the United States now applies to European imports, and the effective floor many Asian exporters must plan around. The administration's actions, negotiations, and carveouts are shifting week to week, creating a sense of urgency. Prices are responding, plans are stalling, and universities are discovering that tariffs don’t just reprice goods; they segment ecosystems—chips, cloud credits, textbooks, even accreditation. In the same year, China is projected to pour as much as US$98 billion into AI capital spending, underwritten by a new state-backed US$8.2 billion fund. A hard tariff wall on one side; an industrial-policy engine on the other. In classrooms from Bangkok to Bandung, the choice no longer reads “which supplier,” but “which stack.” That is why the tariff story is, at root, an urgent education story.

From price shock to pipeline shock

The conventional take treats tariffs as macro noise that the education sector can ride out. That underestimates the impact of a durable 10–15% tariff regime on the micro-economy of learning. Executive actions in April and July introduced and then modified a “reciprocal” tariff framework, while parallel deals produced a flat 15% rate for EU goods—a signal that Washington is willing to normalize elevated duties, not simply threaten them. Court fights may prune the legal basis, but the policy thrust is plain enough for procurement officers to notice. When the price of imported lab equipment, developer workstations, or cloud credits rises and the legal basis wobbles, multi-year syllabi and infrastructure plans wobble with it. For ministries budgeting around five-year cycles, the result is not a transient price bump but an incentive to switch suppliers, platforms, and standards toward the stack they can reliably access.

The export-control environment compounds that incentive. In January 2025, the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security moved—then partially reversed course in May—toward an unprecedented control on closed-weight AI models and tighter rules on advanced computing items. Even with rescission of the “AI Diffusion” rule framework, much of the emphasis on controlling chips, large clusters, and specific model weights persists, and the mere signal of possible licensing in future rounds is enough to make universities think twice about relying on a single, foreign-hosted stack. The administrative churn is the point: standards and access are now policy variables. Education systems that plan for volatility will favor multi-homed compute, bilateral recognition of credentials, and courseware that ports across ecosystems.

If we reframe tariffs as a pipeline shock, the stakes sharpen. In the 1930s, block economies hoarded commodities; today, they hoard compute, standards, and trust in credentials. A 1–2 percentage-point price shock imposed on AI-relevant imports would be survivable in isolation. But layered atop export controls and procurement uncertainty, it nudges systems toward the nearest reliable platform. However, with proactive policy and procurement strategies, these shocks can be turned into opportunities. That is how trade policy becomes curriculum policy, and how we can shape a more hopeful future for education and AI infrastructure.

China’s AI engine, ASEAN’s gravitational pull—and the Japan–Korea question

Against that policy weather, the supply landscape in Asia is rapidly diverging. China’s AI capital expenditure is forecast between ¥600–700 billion (US$84–98 billion) in 2025, and authorities have launched a 60 billion-yuan (US$8.2 billion) fund to feed the early-stage pipeline. The result is a dense mesh of cloud options, accelerator vendors, and model providers prepared to court universities with localized pricing in Southeast Asia. Crucially, much of this capacity arrives physically nearby: Chinese cloud providers are building and leasing facilities across ASEAN, putting low-latency, compliant infrastructure within reach of public universities and vocational institutes that cannot afford U.S. hyperscaler pricing at commercial rates. The gravitational pull is not ideological; it is logistical.

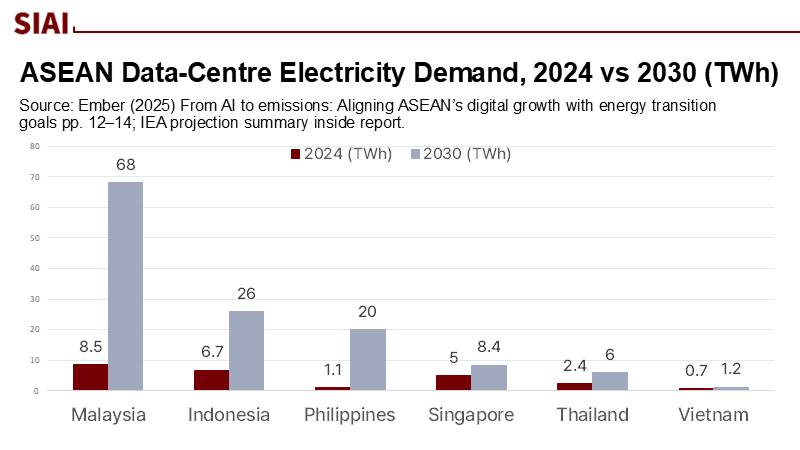

The infrastructure map supports that claim. Alibaba Cloud has opened a third data center in Malaysia and plans to open a second in the Philippines; Huawei Cloud and other Chinese providers are expanding across the region, even as they remain constrained in Western markets. On the demand side, ASEAN’s data-center electricity consumption is projected to nearly double by 2030, with Malaysia alone expected to surge from roughly 9 TWh in 2024 to about 68 TWh by decade’s end—a proxy for the compute that education and research could tap if access arrangements are negotiated early. The point is not that these facilities were built for universities, but that their presence expands the bargaining set for public procurement. Systems that move now can secure “education tiers,” a term referring to the levels of access and quality of services that can be obtained through early adoption of new technologies, while capacity is still being allocated.

Counterweights exist—and they matter. AWS has committed roughly US$9 billion to expand Singapore capacity by 2028, and Singapore-based GPU-as-a-service has begun offering H100-class clusters region-wide. That means ASEAN ministries are not condemned to single-vendor dependence; they can triangulate between the Chinese cloud in Malaysia/the Philippines, and an allied cloud in Singapore, weighting the mix by cost, latency, and export-control exposure. However, the real game-changer is bilateral recognition of credentials. This can significantly enhance cooperation and standardization, making the education-policy foundations for adoption more robust. On governance metrics, Oxford Insights places Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam in the region’s first tier of AI readiness; this is a signal—not a guarantee—that ministries can turn cloud capacity into curricular capacity if they move on teacher training and credential standards.

The Japan–Korea question should be read less as a capability deficit than as a pipeline constraint. Tokyo’s innovation-first AI Promotion Act gives universities a permissive legal frame for testbeds and industry partnerships; Seoul is pursuing scale, publicly targeting procurement of 10,000 high-performance GPUs to anchor a national AI center, while planning a substantial 2026 budget uplift oriented to AI-led growth. Aging demographics will result in tighter student cohorts and salary ladders. Still, in the near term, these systems can supply high-end practicums and faculty exchanges that ASEAN universities can plug into—especially if reciprocal recognition and cross-porting assignments are built into capstones.

What educators should do now: biliteracy, pooled computing, portable standards

The most valuable graduate over the next five years will not be a single-stack specialist but a “block-biliterate” engineer, teacher, or technician who can move fluently between the U.S./allied and Chinese stacks. That is not a rhetorical flourish; it is a curriculum blueprint. Start with the first-year “AI math labs” that teach probability, optimization, and numerical linear algebra alongside GPU programming. Add an intermediate year built around model-lifecycle assignments—data provenance, fine-tuning, safety evaluation—executed twice: once on a U.S./allied platform (CUDA/PyTorch, OpenAI-compatible APIs) and once on a Chinese/open alternative (Ascend/CANN, local API suites). In parallel, embed a shared safety card and documentation standard so that capstones travel. Singapore’s PISA record is instructive here: 41% of students hit the top tiers in mathematics; systems that choose high expectations and aligned supports can absorb technical content at pace. The takeaway is not to imitate Singapore, but to match its clarity on outcomes.

Compute is the binding constraint, so buy it like a region. ASEAN should pool demand for an education-only GPU bank that reserves capacity in Singapore (for allied-stack workloads) and in Malaysia/the Philippines (for Chinese-stack workloads), with a modest sovereign cluster in at least two mainland states for redundancy. The goal is not self-sufficiency; it is predictable access to mixed stacks at education prices. A three-year pooled reservation of a few thousand high-end accelerators—sourced across vendors—would support course-level quotas and research fellowships, with 15–20% capacity carved out for cross-border project teams and teacher-training colleges. The market context is favorable: capacity is being added quickly, and providers on both sides are seeking anchor tenants. If ministries commit early, they can secure telemetry and transparency clauses for model and data handling, and most importantly, price certainty for students.

Standards preserve mobility when politics does not. A narrow standards spine—dataset documentation, reproducibility checklists, incident reporting, and minimal safety tests—should be written once and made stack-agnostic, then embedded into procurement and accreditation. The BIS’s brief foray into controlling “model weights” underscored how quickly access rules can change, and how suddenly a project can become non-portable; ASEAN standards should assume volatility by design. Concretely, capstone projects should be graded on cross-portability: the same model must run on both stacks, with an identical artifacts bundle (weights if permissible, prompts, data sheets) escrowed locally with audit trails. Ministries need not invent all of this in-house; they can draw on existing research reproducibility norms and adapt them to undergraduate and TVET contexts.

The common critiques can be answered. “Isn’t this code for dependence on China?” Not if procurement is deliberately multi-homed and academic outputs must be cross-portable. “Won’t U.S. tariffs fade in court?” Perhaps—but today’s policy environment is already reshaping behavior, and even an adverse ruling in Washington won’t repeal the logic of export-control cycles or the sunk investments ASEAN states are making in nearby data centers. “Can Japan and Korea really anchor regional training if their cohorts shrink?” Yes, if ASEAN leverages them for advanced practicums and faculty exchanges rather than volume teaching. The deeper objection—that building biliteracy cedes ideological ground—misreads the purpose. The aim is not to normalize either stack; it is to teach students to translate between them, and thereby keep options open for the decade ahead.

Turning the agenda into procurement lines. Set three visible deadlines. First, publish a 12-course spine for block-biliteracy by mid-2026, with sample labs released under open licenses and an explicit mapping to TVET certificates and bachelor’s degrees. Second, negotiate an ASEAN Education Compute Facility that reserves capacity across at least three jurisdictions and two vendor families, with telemetry and queueing rules published up front. Third, issue micro-credential standards for “portable capstones” and agree on reciprocal recognition among willing ASEAN, Japanese, and Korean universities. The data-center boom is not a distant prospect; on most forecasts, ASEAN’s sector will double by 2030, and Malaysia’s power demand alone is slated for multi-fold growth. Education can contribute to that growth—but only if it moves while capacity is being allocated.

Where the money meets the model, the U.S. still leads in private AI investment by an order of magnitude; in 2024, U.S. private AI funding was roughly US$109 billion, nearly twelve times China’s US$9.3 billion. That gap indicates where cutting-edge tools will continue to emerge. But capital expenditure is a different variable: Beijing’s ¥600–700 billion AI capex this year pays for the hard things—compute, fabs, power, parks—that make access cheaper next door. For ministries, the lesson is to arbitrage the difference: teach on both stacks, research where you can secure credits and GPUs at scale, and align teacher training to the standards that travel regardless of geopolitics. If tariffs are the tax on indecision, then biliteracy is the hedge against it.

Implications for schools below the university tier. The split will reach secondary schools via content filters, cloud-delivered tutoring, and the identities of the firms that underwrite assessments and teacher PD. We should maintain universal and straightforward guardrails: privacy-preserving analytics, dataset provenance in plain language, and a relentless emphasis on statistical thinking over rote “prompting.” In systems that can afford it, a small, ring-fenced share of pooled compute should be dedicated to teacher colleges and vocational institutes; the payoff is immediate, as industry utilizes the graduates these institutions produce. When procurement officers ask whether such ring-fences are realistic in an era of energy-hungry data centers, point to the region’s expansion numbers and the rise of GPU-as-a-service: capacity is growing, and governments retain leverage if they buy together and publish usage telemetry.

What matters now is that the temptation is to wait for the litigation cycle to conclude and for export-control guidance to be finalized. However, higher education does not operate on quarterly horizons; it operates on cohort horizons. A student who starts a diploma in 2026 will graduate into a world of stacked toolchains and political contingencies. The systems that act now—designing biliterate curricula, buying pooled compute, and locking in portable standards—will ship graduates who can work anywhere, with anyone, on anything that meets baseline safety and documentation. The systems that delay will inherit syllabi tied to whichever vendor offered a quick discount in 2024–2025, and will spend the next decade unpicking those decisions. The policy north star is not autarky; it is freedom to choose, class by class and project by project. That is what sovereign education looks like in a blocked world.

We began with two numbers: a tariff floor and a capex surge. The first is already rewriting procurement spreadsheets and cross-border contracts; the second is already reshaping where ASEAN’s compute sits and who can afford to rent it. Treat the combination as an opportunity, not a trap. Ministries should commit—before this academic year ends—to a biliterate spine that forces students to ship on both stacks; to a regional GPU bank that buys time, literally, for classrooms; and to a minimalist standards passport that keeps work portable no matter how court rulings or export rules swing. The U.S. investment engine will keep throwing off new tools; China’s industrial machine will keep laying concrete and cables; and ASEAN’s data-center curve will keep racing upward. If educators act now, they can transform tariff noise into a valuable human capital signal. The right graduates—fluent in both dialects of AI, trained on shared standards, comfortable switching stacks—will insulate schools from politics by making their students indispensable to both sides. That is how public education converts a trade shock into a decade of strategic advantage.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Alibaba Cloud. (2025, July 1–3). Third Malaysia data center; second in the Philippines (October plan). Reuters; DataCenterDynamics; Economic Times.

Bureau of Industry and Security (U.S.). (2025, Jan.–Feb.). Interim Final Rule on advanced computing ICs and AI model weights; associated summaries and client alerts. Sidley; Covington; KPMG; Freshfields;

Ember. (2025, May 27). From AI to emissions: Aligning ASEAN’s digital growth with decarbonisation (report and web chapter).

Future of Privacy Forum & IAPP. (2025, Jun.–Jul.). Japan’s AI Promotion Act: Innovation-first governance.

Oxford Insights. (2024–2025). Government AI Readiness Index 2024 (report and ASEAN brief).

OECD. (2023–2024). PISA 2022: Country notes—Singapore; Volume I.

Reuters. (2025, July 2). Alibaba Cloud expands in Malaysia and the Philippines.; (2025, Jun. 18). Malaysia data-center power demand outlook.; (2025, Aug. 21–29). South Korea budgets for AI-led growth.

Reuters / Fortune / Tech in Asia. (2025, Feb. 16–18). South Korea aims to secure 10,000 GPUs for a national AI center.

Singtel. (2024). GPU-as-a-Service initiatives (H100 clusters) and Nscale partnership.; WSJ coverage.

South China Morning Post; TechWireAsia; Tech in Asia. (2025, June–July). China’s AI capex forecast at US$84–98 billion; launch of 60 billion-yuan AI fund.

Stanford HAI. (2025). AI Index 2025: Private investment by country (U.S. $109.1B vs China $9.3B in 2024). (PDF and Economy chapter).

U.S. Executive Office. (2025, Jul. 31). Further Modifying the Reciprocal Tariff Rates (Executive Order 14257 background).

Washington Post & Wall Street Journal. (2025, Sept. 4). Administration seeks Supreme Court relief to sustain global tariffs.

Wire services (Reuters). (2025, Sept. 3). EU official confirms 15% U.S. tariff rate context and flows under new deal.

Comment