Modeling People, Not Mannequins: Teaching Economics to Capture Real Heterogeneity Without Abandoning Rigor

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

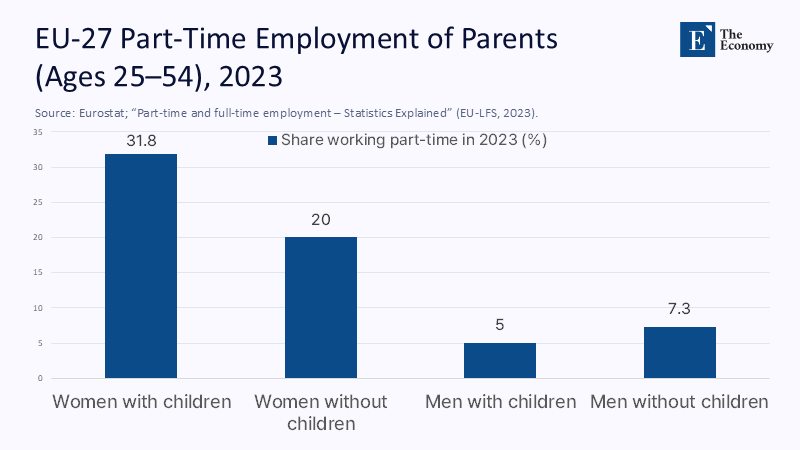

A statistic we cannot dodge: as recently as 2023, the median gender wage gap across the OECD was about 11.5%, meaning the median full-time woman earned roughly 88 cents for every male dollar; in the European Union, nearly one in three mothers aged 25–54 worked part-time compared with just one in twenty fathers; and in the United States, six in ten parents reported spending at least 20% of household income on child care. These three numbers describe a labor market in which the "average worker" is a fiction and the typical week is a moving target. They also explain why policies designed around a gender-neutral representative agent regularly misfire: they treat time, liquidity, and care constraints as noise instead of the signal. The upshot for economics education is immediate. We should keep the representative agent as a scaffold for clarity, but teach students—early and often—how, when, and why to replace it with a structured portfolio of types that captures the margins where behavior truly moves. Anything less is pedagogy that underfits reality.

From Identity to Structure: Reframing Heterogeneity in Economic Models

The current conversation too often treats naming identity categories as modeling. We should reframe the issue. The problem is not the representative agent per se, but the unexamined leap from an elegant benchmark to policy claims in economies where aggregation conditions are violated. When preferences admit Gorman aggregation or markets are complete, a composite agent can summarize the economy; when they do not, the composite must be a weighted portfolio that preserves the margins that move behavior—time availability, liquidity, and risk exposure. Recent advances make this operational: we now have tools to predict and decompose differences between representative-agent (RA) and heterogeneous-agent (HA) models, and separate domains where RA approximations are acceptably accurate from those where they flip signs. That is precisely how disciplined heterogeneity should enter the classroom and the policy memo: as a method with conditions, not a slogan with exclamation marks. Doing so keeps the base model for intuition while forcing transparency about which heterogeneities—gender, education, region, income—matter for the question at hand.

Why Now: Post-Pandemic Labor Markets Expose the Limits of Neutral Defaults

By mid-2024, the OECD unemployment rate hovered near 5%, a historically low figure; in most countries, women's employment rates advanced relative to pre-pandemic levels, yet the dispersion across countries stayed large. In Q4 2023, Finland's employment rate for women edged above men's by about half a percentage point, while gaps remained immense—above 25 percentage points—in Türkiye, with similarly wide differentials in Costa Rica and Mexico. These are not neutral backgrounds. They are institutional landscapes in which school-day length, parental leave design, local tax rules, and childcare subsidies either compress or widen the feasible set for households. A neutral RA worker cannot represent an economy where the binding constraint for a mother is a nursery place at 2 p.m., while for a father it is a marginal tax notch at 7 p.m. overtime. Instructors who still present labor supply as a single smooth function around a single agent risk teaching the right calculus on the wrong problem. The labor market's post-pandemic resilience made the structural fractures easier to see.

Evidence with Edges: What the Numbers Say—and What We Estimate

The contemporaneous facts are clear. Across the OECD, the median gender wage gap was about 11.5% in 2023. A multiple-country meta-analysis pooling more than 2,000 estimates finds a robust "motherhood penalty" in wages—modest on average per child but sizable in the short run around births and persistent without supportive policy. Within the EU in 2023, 31.8% of employed mothers aged 25–54 worked part-time versus 5.0% of fathers, and Germany remains striking, with roughly half of employed women working part-time compared to about one in eight men. If we take a conservative back-of-the-envelope approach—combine a 12% wage gap with a 0.5 probability of part-time for mothers in high-cost childcare settings and assume part-time hours reduce earnings by one-third—we estimate a lifetime earnings shortfall for median mothers of roughly 20–25% relative to comparable fathers, before compounding. That estimate is transparent and adjustable: change the childcare subsidy or the probability of part-time, and the wedge moves mechanically. Notably, the ILO shows that including informal work widens gaps further in lower-income settings—another reminder that the representative agent cannot carry the policy load alone.

Implications for Educators: A Curriculum That Teaches Disciplined Diversity

Economics classrooms should treat heterogeneity as a design problem, not a declaration. In intermediate micro, begin with an RA benchmark and then perturb it along four margins likeliest to break aggregation: time (household production and caregiving shocks), liquidity (hand-to-mouth behavior and credit limits), risk (idiosyncratic shocks with incomplete insurance), and institutions (tax and transfer kinks). Require students to calibrate each perturbation with disaggregated data—sex, education, income quintile, region—so they see which heterogeneities move the comparative statics. In macro, pair an RA model with a HANK-style environment and have students compute impulse responses to a childcare subsidy, a payroll-tax notch, and a school-day extension; grade them on the clarity of the mapping between data moments and modeled margins. Close the loop with communication training: students should defend when an RA summary is sufficient, when a two-type split (e.g., caregivers vs. non-caregivers) is necessary, and when only a richer portfolio of types will do. This is how we teach rigor without losing reality.

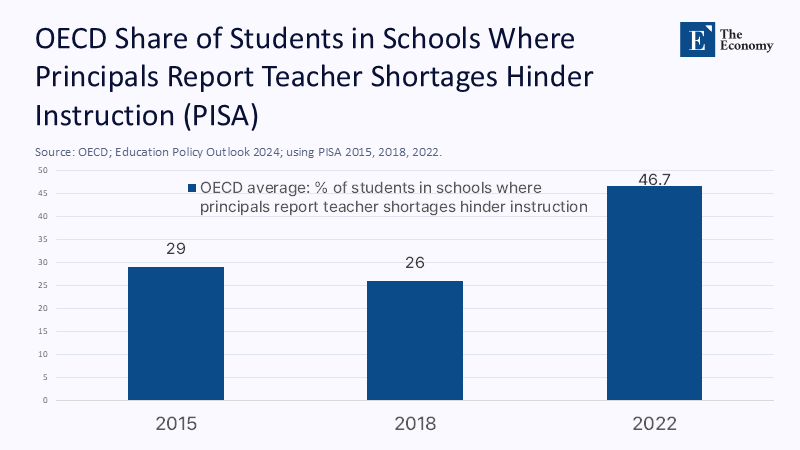

Implications for Administrators: Designing Institutions Around Lifecycle Spikes

Schools and universities are labor markets with predictable, gendered spikes in time demand—pregnancy, infant care, elder care—that collide with rigid timetables. Globally, women make up about two-thirds of primary teachers and a majority at secondary levels. Yet, leadership remains disproportionately male, and systems face mounting teacher shortages projected to reach 44 million worldwide by 2030. Meanwhile, the share of students in OECD systems whose principals report teacher shortages rose from roughly 29% to nearly 47% between 2015 and 2022. These facts argue for administrative reforms that treat time as capital: schedule governance meetings inside core hours; align staff development with school-day coverage; extend or stagger nursery and after-school hours; and design parental-leave backfilling that does not penalize career trajectories. Where the teaching corps is heavily female but leadership is not, mentorship and transparent promotion criteria should be coupled with schedule redesign, not offered as substitutes for it. Administrators don't need a new ideology to act; they need a timetable that acknowledges heterogeneity in the constraint set.

Implications for Policymakers: Target Design Beats Identity-Only Design

Identity-aware policy is necessary; margin-targeted policy is effective. Mandating disclosure of gender pay gaps—now required in just over half of OECD countries—raises transparency and can shift norms, but it is blunt on the constraints that suppress hours. Childcare affordability, by contrast, acts directly on the time-income trade-off. When net childcare costs approach one-fifth of disposable income, as they do for many families, female labor supply becomes highly elastic at the intensive margin; reducing that wedge shifts hours more than rhetoric ever will. Transparent childcare subsidies and tax credit phase-ins, aligned with school-day length, should be modeled as shocks to the time budget as well as to disposable income. Similarly, policies that move part-time penalties—such as prorating benefits and smoothing cliff effects—alter the feasible set for parents in measurable ways. If we teach future policymakers to write down these margins, we will see fewer laws that declare equity and more that deliver it.

Anticipating the Critiques—and Answering Them on the Merits

One familiar critique says the representative agent is "made of sand," and adding heterogeneity merely builds a taller dune. A better reading of the literature is humbler and more useful. We now have formal diagnostics that decompose where RA and HA predictions differ, allowing us to show when aggregation errors are small enough to ignore and when they overturn signs. We also know, from modern aggregation results, when heterogeneity in beliefs can be summarized without loss and when it cannot. Empirically, labor markets with large caregiving shocks, indivisible hours, and incomplete insurance are precisely where RA approximations fail and where modeling structured types earns its keep. None of this requires abandoning the base model; it involves training students to respect its domain of validity. The payoff is two-fold: sharper optimistic predictions and more credible normative analysis, especially for education and family policy, where time constraints and institutional schedules are first-order.

Keep the Base, Sharpen the Lens

Please return to the three numbers we began with: a double-digit wage gap, part-time rates for mothers that dwarf those for fathers, and childcare costs that consume a fifth or more of family budgets. Together they reveal a simple truth: what looks like a neutral labor market is, in fact, a tightly coupled system of time, cash, and institutional rules. The representative agent still has a place, as a scaffold that clarifies mechanisms and a benchmark for counterfactuals. But our teaching and policy must train practitioners to swap it out whenever aggregation fails, and to do so with disciplined, data-anchored heterogeneity across the margins that matter most. Economics education should be the workshop where this muscle is built. If we keep the base and sharpen the lens, we can design curricula and policies that stop pretending people are mannequins and start treating them as they live—constrained, adaptive, and diverse in systematic ways.

The original article was authored by Navika Mehta, the Strategic Communications and Research Dissemination Lead at the International Economic Association's Women in Leadership in Economics Initiative (IEA-WE). The English version of the article, titled "Gender-neutral economics can no longer be the default," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Ahn, S., Kaplan, G., Moll, B., Winberry, T., & Wolf, C. (2021). Predicting and decomposing why representative agent and heterogeneous agent models differ. *Journal of Economic Dynamics

Bank of America Institute. (2024). High childcare costs threaten women's progress

Eurostat. (2024). Part-time and full-time employment—Statistics explained

International Labour Organization. (2024–2025). Global Wage Report 20

Le Monde. (2024, September 2). Why women's working hours in Germany are still hindering the country's growth

OECD. (2023). Gender equality at work

OECD. (2024). Employment Outlook

OECD. (2024). Education Policy Outlook

OECD. (2024). Society at a Glance 2024: Emplo

OECD Data. (n.d.). Net childcare

UNESCO GEM/Teacher Task Force. (2024). Global Report on Teachers

UNESCO. (2025). Education: Report calls for more women at the top

Zimper, A. (2023). Belief aggregation for representative agent models.

Comment