Two Tariffs, One Strategy Problem

Input

Changed

U.S. tariffs mix security aims with bargaining, causing confusion. Allies hedge by shifting trade and investment toward China and cheaper energy, blunting U.S. leverage Policy needs clear, separate goals.

If one number captures the confusion in the current U.S. trade strategy, it is 50. In late August, Washington raised tariffs on many Indian goods to as high as 50% to punish New Delhi for purchasing discounted Russian crude. This decision caused immediate financial repercussions: the rupee fell to a record low, and foreign investors withdrew about $11.7 billion from Indian markets this year. The U.S. trade strategy, which involves a combination of tariffs and negotiations, is designed to protect American industries and gain leverage in international trade. Meanwhile, India's energy situation hasn't changed much—discounted Russian oil continues to flow and might even increase again in September. This situation highlights the confusion of using tariffs as both a national-security tool and a bargaining chip: national security calls for consistency and coalition-building, while bargaining relies on shock value. Blending the two causes partners to hesitate, often strengthening ties with China, which Washington aims to limit.

The Logic Trap Behind "Two-Purpose" Tariffs

The United States established a broad tariff system in 2025. It includes a universal 10 percent baseline under national-emergency powers, additional 'reciprocal' surcharges, which are tariffs imposed in response to similar tariffs imposed by another country, and now a 50% rate on Indian imports tied to Russian oil. This system muddies the purpose. When tariffs are framed as national security, they seem permanent; when seen as leverage, they appear reversible. Partners cannot effectively plan factories, pipelines, or curricula around policies that switch between the two. Legal uncertainty adds to the issue, as court challenges concerning presidential tariff authority introduce more risk. In this uncertain environment, allies tend to lean toward self-insurance, expanding market options in China or the Global South to balance U.S. instability. This isn't a moral failing; it's responsible management.

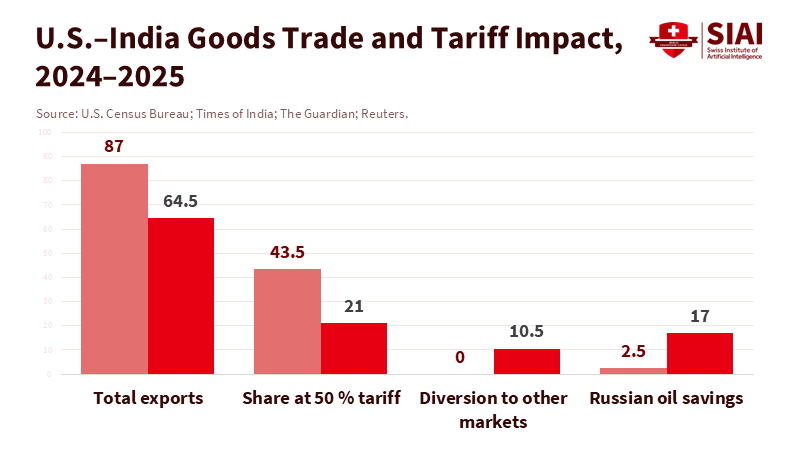

The Indian example illustrates these trade-offs. In 2024, the U.S. and India exchanged $129 billion in goods, with the U.S. facing a $45.8 billion deficit. A 50% tariff risks significantly reducing over a third of India's exports to its top market, particularly in textiles and light manufacturing, where profit margins are slim and alternatives are easy to find. Analysts in New Delhi warn that this could decrease India's GDP by 0.5 to 0.6 percentage points this fiscal year. Ratings agencies in India expect a 5 to 10% revenue drop for home textiles alone. However, this same tariff has made Russian oil cheaper for India, meaning the penalty intended to limit Moscow's war funding may unintentionally expand the market that supports it. Essentially, as a negotiation strategy, the tariff is bold; as a security measure, it has flaws.

A similar dual nature has emerged in technology controls. Washington has tightened approvals for advanced chip equipment to China and briefly revoked exemptions for Korean manufacturers, only to introduce annual licenses that allow for tighter oversight. Markets interpret this as uncertain—a "maybe yes, maybe no." For companies with multibillion-dollar factories in China and extensive suppliers in the region, these fluctuations are critical business concerns. The diplomatic request is that allied companies accept lower profits and greater risks for U.S. security. In return, they expect reliable access, funding, or protection from retaliation. Mixed signals lead to the opposite effect.

How Allies Rebalance When America Closes a Door

India's quick response demonstrates how rapidly global demand and investment can shift. After the 50% tariff, the rupee hit 88.44 per dollar as investors moved away from risk. Delhi combined quiet foreign exchange intervention with tax relief while continuing to import inexpensive Russian crude—official and media estimates suggest savings of about $2.5 billion to $17 billion since the onset of the Ukraine war. This range is significant: even with conservative estimates, the energy discount softens the tariff shock, and Russian shipping schedules are adapting to keep India as a key buyer. In other words, the policy meant to reduce India's Russian energy imports instead expands the strategic black market around it.

South Korea's semiconductor situation is no less telling. SK Hynix is estimated to produce 30 to 40% of its memory chips in China, and Samsung makes about a third of its NAND chips there. When exemptions end or oversight becomes tighter, these companies can shift sales more quickly than they can adjust their manufacturing. In 2024, Samsung's exports to China jumped to around ₩64.9 trillion (about $44.8 billion), surpassing exports to the U.S. If U.S. incentives fluctuate and compliance rules vary from quarter to quarter, the easiest route is to ensure the revenue from China while waiting for Washington to make its next move. The idea that tariffs or sporadic approvals alone will pull manufacturing out of China overlooks existing costs and overestimates the stability of policy.

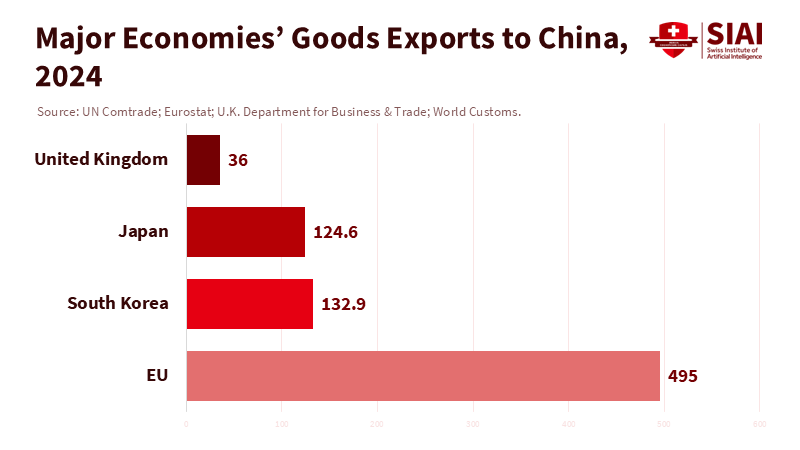

Europe finds itself on the same tightrope. The EU reported a goods-trade deficit with China of about €304 to €306 billion in 2024, despite efforts to "de-risk." The relationship is too significant to ignore, leading to a tariff tit-for-tat: Brussels is targeting Chinese electric vehicles while Beijing retaliates with duties on EU pork that reach as high as 62.4%. The UK, meanwhile, emphasizes engagement—China remains its third-largest trading partner, and the new trade secretary has revived talks to remove about £1 billion in barriers. For European universities, automakers, and agribusiness, the message is clear: any action that limits U.S. access without a coordinated allied strategy will be countered by stronger commercial ties with China.

The United Kingdom's data highlights this point. UK exports to China hit £28.8 billion in the year leading up to Q1 2025, even as London tightened restrictions on Chinese investments in sensitive areas. Japan's exports to China were about $125 billion in 2024, while South Korea's were roughly $133 billion. These figures fluctuate with the economic cycle, but the constant factor is exposure. When the U.S. measures blend security and leverage, partners diversify towards the market, seeing the fastest growth and the deepest manufacturing base. That market is rarely the United States.

A simple estimate illustrates how substitutions weaken leverage. Assume Indian goods worth $87 billion were shipped to the U.S. in 2024, with half facing the new 50% tariff. If the pass-through to U.S. prices is 70% and the import demand elasticity is -1.5, U.S. buyers will reduce orders of those affected goods by around 52%. This suggests about $22 to $23 billion in lost sales for India in the U.S. If India redirects half of that to other markets at a 10% to 15% discount, the revenue loss shrinks to $10 to $12 billion—painful but manageable and likely offset over time by cheaper energy costs. The leverage weakens unless allied demand acts in unison.

What a Coherent Playbook Would Look Like

A clear strategy distinguishes tools based on objectives and timelines. If the goal is national security—preventing adversaries from accessing certain areas—export controls and targeted tariffs should be rule-based, legislated when possible, and designed with allied offsets. For example, if Samsung and SK hynix lose market flexibility in China, Washington and its partners should establish multi-year, statutory incentives for diversification to reliable hubs, while keeping predictable, annual carve-outs for legacy operations in China that don't upset the military balance. If the aim is negotiation—gaining market access or aligning views on Russia—tariff tools should have set timelines, be transparent, and have precise expiration dates unless coalition goals are met. Mixing these approaches encourages partners to hedge; clarity establishes supply-chain and capital-expenditure planning across the alliance.

Policy design must also consider domestic costs that can reduce political support. Independent analyses suggest the tariff system acts like a broad tax on U.S. households—around $1,300 for each household this year—while creating compliance risks for small exporters. This doesn't mean tariffs are always inappropriate; it does imply they should have a narrow scope, include transparent exemptions for allies that meet verified security standards, and have pre-announced review periods. When implemented correctly, tariffs can lead to a rules-based outcome rather than becoming an ongoing operating procedure.

For educators and system leaders, the implications are clear. Universities preparing future trade lawyers, engineers, and supply-chain leaders should view the tariff-control mix as a current case study in institutional design—how to create rule-credibility amid uncertainty. Business schools can teach procurement simulations that involve a 10% universal tariff and a fluctuating 25-50% surcharge, prompting suppliers to re-optimize their strategies, revise budgets, and adjust inventory levels in response to geopolitical factors. Technical institutes can now offer micro-credentials in export compliance and chip-tool safety to small and medium-sized enterprises navigating the new licensing landscape. International offices should assess the risks associated with China-related partnerships and develop dual-track programs that remain viable under both "security-first" and "leverage-first" U.S. policies. In a situation where signals change, resilience comes from having options.

Administrators should also prepare for disruptions in student mobility and research related to trade conflicts. The friction between the EU and China over electric vehicles and agricultural products shows how quickly industry tensions can affect visas, funding, and data-sharing. Contingency plans with partners in India, Korea, and Southeast Asia can maintain exchange channels even during a U.S.-China standoff. For vocational programs, align capstone projects with the diversification strategies that companies are actually pursuing—such as Mexico for vehicles, Southeast Asia for electronics, and India for pharmaceuticals and IT—so graduates meet the needs within the risk frameworks businesses currently use. This same approach can help workforce agencies retrain employees in sectors most affected by retaliatory tariffs.

Critics may argue that the bluntness of tariffs is intentional—that surprise is the goal. However, surprise diminishes quickly. India's response shows that the easiest way to counteract a loss in U.S. margins is by turning to cheaper Russian oil and greater discounts from other buyers. Korea's experience suggests that when approvals appear transactional, firms tend to rely on revenue from China while reducing investments elsewhere. Europe's statistics confirm that, despite verbal commitments to de-risk, the structural deficit with China persists, and retaliatory measures can exacerbate it. A leverage-focused approach can't yield secure outcomes if partners reasonably seek alternatives. A security-first perspective cannot provide leverage if partners see no stable pathway towards shared regulations. The skilled approach is to choose clearly—and then design transparently.

The 50% tariff on India was presented as a strategy for exerting pressure, but it actually served as a price indicator. It communicated to partners that the United States would shift between punishments and demands, encouraging markets to mitigate U.S. instability by exploring non-U.S. options—particularly those in China. If the aim is to limit Beijing's strategic space while increasing pressure on Moscow, this approach backfires. A more effective strategy is doctrinal minimalism: clearly distinguish between security controls and bargaining tariffs; legislate the former and set expiration dates for the latter; establish compensation frameworks for allied businesses that are expected to bear increased risks; and provide a clear timeline that markets can interpret. Coalition strength relies on credible rules paired with economic reality. Right now, the rules appear improvised, and the market is leading the way. Change the signal—once and clearly—and the numbers will start to move in the right direction.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Deccan Herald. (2025, Aug. 28). Benefit from Russian oil imports exaggerated; India's actual gain at just $2.5 billion.

European Commission (Eurostat). (2025, Mar. 4). Slight decline in imports and exports from China in 2024 (EU goods deficit ≈ €304.5 billion).

J.P. Morgan Research. (2025, Aug. 11). U.S. Tariffs: What's the Impact?

KED Global. (2025, Sept. 9). U.S. likely to grant Samsung, SK hynix conditional approval (annualized China gear approvals).

Reuters. (2025, Sept. 11). India rupee sinks to record low; U.S. tariffs keep outlook fragile.

Reuters. (2025, Sept. 1). Shares in Samsung, SK hynix drop after U.S. makes it harder to produce chips in China.

Reuters. (2025, Sept. 9–11). EU–China trade developments; UK engagement with China (EU pork duties; UK JETCO revival).

The Guardian. (2025, Aug. 27). Trump imposes 50% tariff on India over Russian oil purchases; Explainer: How hard will the 50% tariff hit?

Tax Foundation. (2025). The economic impact of the Trump tariffs (≈ $1,300 per U.S. household).

Times of India. (2025, Sept. 3). The 50% misfire: How Trump made Russian oil cheaper for India—and Putin a winner.

TrendForce / Yonhap. (2025, Mar. 13). Samsung & SK hynix post strong 2024 China sales; Samsung exports to China ≈ ₩64.9 trn.

UK Department for Business & Trade. (2025, Aug. 1). China—UK Trade and Investment Factsheet (UK exports to China ≈ £28.8 bn, Q2 2024–Q1 2025).

U.S. Census Bureau / USTR. (2024–2025). U.S.–India goods trade: totals and balance.

White House. (2025, Apr. 2). Fact Sheet: President Trump declares national emergency; 10% baseline tariff on all imports.

World Customs / TradingEconomics (UN Comtrade mirror). (2025). Japan and Korea exports to China (2024): Japan ≈ $124.6 bn; Korea ≈ $132.9 bn.

Comment