Two Stars, One Fracture: Why Education Policy Must Plan for a Bi-Polar Global Economy

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

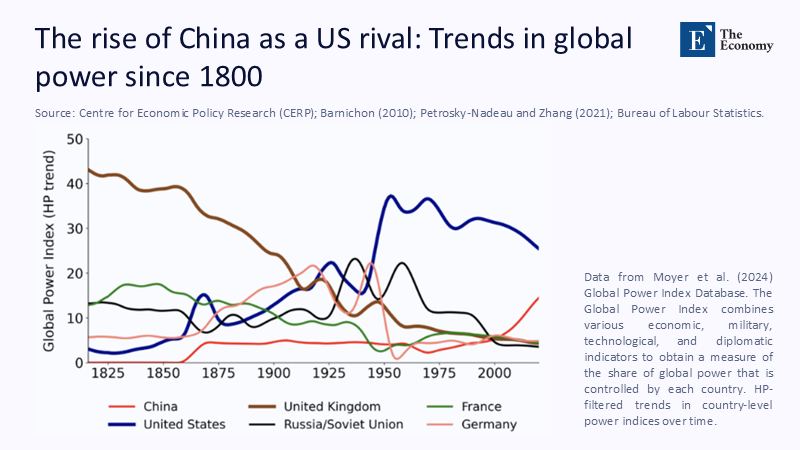

Since Russia invaded Ukraine, trade between countries in opposing geopolitical blocs has fallen about 12% relative to trade within blocs—and cross-bloc greenfield investment has dropped 20%—even as overall globalization, by crude measures, hasn’t collapsed. That’s the International Monetary Fund’s latest read of the wiring behind the world economy: flows are not dying; they are being rerouted along political lines. At the same time, the US tariff rate has been pushed to its highest level since 1934, averaging roughly 18% after this spring’s actions, and Washington’s net interest bill is on track to top $1 trillion within a year, narrowing its fiscal room to cushion the shocks that fragmentation creates. Put simply, the global “mesh” that once connected almost everyone to everyone is hardening into two rival “star” networks with Washington and Beijing as competing hubs. Education policy cannot afford to treat that as distant geopolitics. It is the operating system under our research partnerships, student flows, scientific supply chains, and institutional finances.

Reframing the Problem: From “Who Leads?” to “What Topology Wins?”

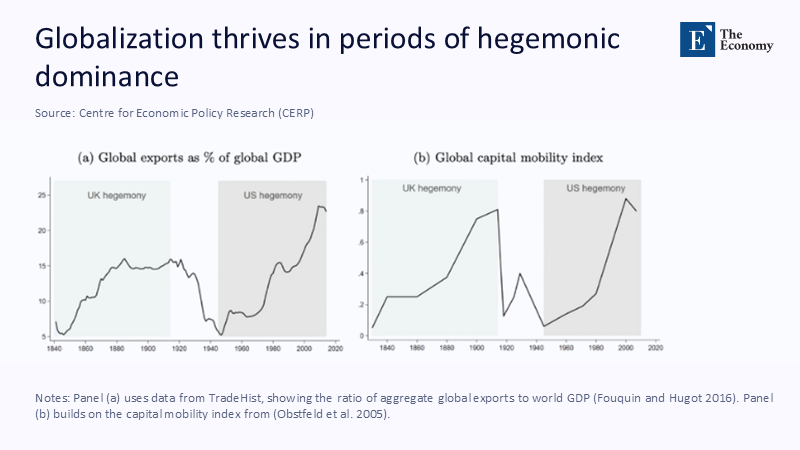

The conventional question is whether globalization “needs” a single hegemon to anchor rules and reduce frictions. The more urgent question now is topological: what happens when two hegemons each prefer to be the hub of a star network and see limited marginal gains from a direct link to the other hub? Classic network theory tells us that star designs concentrate control and streamline delivery, while fully mesh designs distribute connections but impose heavy overhead. In communications engineering, the star is efficient until the hub fails; in global political economy, two stars coexisting—each seeking alignment and compliance—generate recurrent stress as their peripheries are pruned and re-wired. That is the world education systems must plan for: not deglobalization, but re-polarized globalization. The evidence is visible in treaty patterns and policy alignment studies, which show integration surging under a dominant hub and fragmenting when hegemons diverge in standards or strategy. Historically, the last great swing to bipolarity ended only when one star collapsed; until then, the system created steady tension rather than stable efficiency. For schools, universities, and ministries, the relevant policy move is therefore not to pick a side reflexively, but to design for dual-hub interoperability.

What the New Data Say—and How We Scaled It

WTO tracking shows world merchandise trade fell 1.2% in 2023 but is projected to recover by 2.6–3.3% in 2024–2025, which may look reassuring until we notice that recovery is lopsided: the composition of flows is tilting inward toward like-minded partners. This shift requires us to be proactive in our planning. The IMF’s gravity-model estimate—a 12% relative decline in cross-bloc trade and 20% drop in cross-bloc FDI since 2022—implies a sizable realignment even if the global trade/GDP ratio stays flat. To translate this into magnitudes, start with the WTO’s estimate of roughly $32.2 trillion in international trade in 2024 (goods plus services). Assume—conservatively—that 30% of flows are cross-bloc; apply the IMF’s 12% relative decline; you’re looking at on the order of $1.2 trillion in trade redirected or foregone compared with a neutral baseline. This is a back-of-the-envelope meant to illuminate scale, not to certify loss: some of that $1.2 trillion detours through “connector” countries such as Mexico or Vietnam rather than vanishing. The key insight is that frictions are rising and routes are lengthening, especially in complex supply chains. We must plan for these changes and be prepared to adapt.

From Trade Maps to Campus Maps: Why This Matters for Education Now

Education systems are not spectators. They are prominent economic actors whose business models depend on cross-border flows of people, equipment, data, and money. OECD counts the number of international students in OECD countries above 4.6 million by 2022, with the highest mobility in STEM fields, where roughly 30% of students are international. If we take that 4.6 million and apply our conservative IMF-based cross-bloc friction estimate to just one-fifth of those flows—students who plausibly traverse bloc lines in STEM and advanced tech programs—the implied at-risk channel is nearly 920,000 students; a 12% friction-related hit would be roughly 110,000 fewer cross-bloc students, or a mandatory rerouting toward “friendly” destinations. Even if the global headcount keeps growing, the direction of mobility will tilt, altering tuition revenues, research staffing, and the talent composition of graduate cohorts. Layer onto that the export-control landscape: US rules on advanced computing and semiconductor manufacturing items were tightened in October 2023 and again in 2024–2025, with enforcement that now extends to AI model weights. Universities with joint labs, dual-use equipment, or industry-sponsored chip research face longer compliance cycles, more denied parties screening, and higher audit costs. In a two-star world, campus risk management becomes a front-line policy domain.

The Economics of “De-Risking” Are Not What They Seem

Proponents of sharp decoupling promise resilience. The modeling says: be careful. IMF simulations of large-scale reshoring show long-run global GDP losses of around 4.5%; friend-shoring scenarios still cut output by up to 1.8%. OECD work points to similar hazards: aggressive localization can suppress trade, raise prices, and not deliver meaningful resilience if it simply shifts risk without rebuilding missing inputs. BIS research adds a nuance that matters for labs and classrooms: rather than simplifying supply chains, fragmentation is lengthening them and rerouting them through third countries, adding choke points and latency without reducing strategic dependencies. In this environment, the “two stars” don’t cancel risk; they multiply it in different parts of the network. For education budgets, this is reflected in pricier imports of lab equipment, slower delivery of specialized components, and duplicated compliance costs across parallel standards. For students and scholars, it means visa volatility and sudden constraints on collaborations in sensitive domains. “De-risking” can easily become re-risking unless policy leans hard into interoperability rather than isolation.

Translating the Findings: What Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers Should Do

If the wiring diagram is shifting from a global mesh to two stars with connectors in between, the strategy must follow the physics of the network. For educators, that means designing curricula and research training that are standards-bilingual—teaching students how to navigate export controls, data localization rules, and documentation practices that now diverge across blocs, especially in AI, quantum, and biotech. For administrators, it means rebuilding international portfolios around connector geographies whose legal regimes allow collaboration with both hubs—think of Mexico, Vietnam, India, or the Gulf—while hardening internal review for projects that touch controlled technologies. For policymakers, it means prioritizing interoperability where national-security aims do not require walls: mutual recognition of degree programs and safety standards; transparent carve-outs for basic science and researcher mobility; visa policies that insulate students from tariff volleys. The fiscal context matters: with US net interest soon north of a trillion and tariff shocks rippling through the service sector, public buffers are thinner and volatility spreads faster. The lowest-cost way to buy resilience is to shorten the routes our most critical knowledge flows must travel, even as trade lanes grow longer.

Anticipating the Pushback—and Rebutting It

Three critiques usually surface. First, that fragmentation is modest and reversible. True, the IMF calls it early days, but the direction is unambiguous, and policy instruments—from tariffs to targeted tech controls—are still tightening. Commerce’s 2023–2025 rules, GAO’s implementation audit, and recent enforcement actions show more gates, not fewer. Second, that decouples disciplines and brings supply home. Yet the most careful modeling suggests substantial output losses with limited resilience gains because bottlenecks reappear in the very third countries that now intermediate flows. The US import shift from China toward Mexico and Southeast Asia did not sever the input trees whose roots still run through Chinese ecosystems; it re-mapped customs codes and extended the route. Third, that universities should “stick to teaching” and ignore geopolitics. But the empirical reality is that STEM mobility and cross-border research productivity are most exposed to politics, and the funding and equipment that power labs are moving through the same congested arteries as everything else. Serious education policy must therefore adopt a network engineer’s mindset: minimize single points of failure, build redundancy only where it yields true optionality, and resist costly duplications that add bureaucracy without buffering risk.

What Breaks the Star? Scenarios and Early Warning Lights

Two-hub systems end either when one hub weakens or when the benefits of a direct hub-to-hub link rise enough to justify a bridge. Today, neither looks imminent. Fiscal pressures in the US—increasing net interest and the risk that higher yields “crowd out” public investment—limit slack for generous buffer policies. China, for its part, is pushing indigenous platforms while absorbing sanctions and controls that nudge it to build parallel standards. That leaves the connectors as pivotal. If they can arbitrage standards—hosting joint labs that comply with both sets of rules, manufacturing specialized components with verifiable provenance, enabling encrypted data enclaves usable by both blocs—then the effective “distance” between hubs shrinks without a formal détente. Watch for metrics like the share of announced FDI projects within versus across blocs; watch service-trade growth in digitally delivered education; watch whether student visas in STEM become politically insulated. If those lines move toward openness, tension eases. If not, the stars drift further apart, and the cost of duplication climbs, especially for capital-intensive research.

The Shortest Path Is the One We Build

The clearest signal in today’s data is not that globalization is ending, but that it is re-sorting. Cross-bloc trade and investment are down 12% and 20% relative to within-bloc flows, respectively, while total volumes limp along. That pattern—two stars pulling their peripheries tight—will keep producing friction until either a bridge is laid between the hubs or one hub fails. Education cannot wait on either outcome. The practical task is to shorten the path for knowledge, talent, and ideas within this fractured map: standards-bilingual curricula, connector-country partnerships, interoperable compliance, and carved-out channels for basic science and student mobility. National security will—and should—constrain some links. But absent a deliberate plan to keep the essential arteries open, we will pay more to learn less, train fewer innovators, and discover more slowly. The call to action is simple: treat the world economy as the network it has become, and start engineering for reliability. If we build the shortest paths where we can, the stars matter less, and learning travels faster.

The original article was authored by Fernando Broner, a Research Professor at Barcelona School of Economics, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Why globalisation needs a leader: Hegemons, alignment, and trade," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Aiyar, S., et al. (2024). Geoeconomic Fragmentation and “Connector” Countries (MPRA paper). University of Munich.

Baker McKenzie. (2024, Dec. 6). US Department of Commerce significantly expands controls targeting indigenous production of advanced semiconductors in China.

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). (2024). A theory of economic coercion and fragmentation (BIS Working Paper No. 1224).

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). (2025). Qiu, H., Xia, D., & Yetman, J., The role of geopolitics in international trade (BIS Working Paper No. 1249).

Bipartisan Policy Center. (2025, Feb. 4). Visualizing CBO’s Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025.

Business Insider. (2024, Feb.). Mexico surpasses China as top US trading partner.

CEPR VoxEU. (2025, Aug. 2). Broner, F., Martín, A., Meyer, J., & Trebesch, C., Why globalisation needs a leader: Hegemons, alignment, and trade.

CEPR VoxEU. (2025, Aug. 1). Hayakawa, K., & Ito, K., The ripple beyond borders: Indirect effects of US export controls on Japanese firms.

Census Bureau (US). (2025, June). Top trading partners – Year-to-date total trade.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). (2025, Jan. 17). The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035.

CloudMyLab. (2025, July 22). Star Network Topology Explained: Advantages and Use Cases.

Federal Register (US). (2023, Oct. 25). Export Controls on Semiconductor Manufacturing Items.

GAO (US). (2024, Dec. 2). Commerce implemented advanced semiconductor rules but faces challenges (GAO-25-107386).

IMF. (2024, Apr.). Gopinath, G., Gourinchas, P-O., Presbitero, A. F., & Topalova, P., Changing Global Linkages: A New Cold War? (WP/24/76).

IMF. (2024, Jun. 21). Cerdeiro, D., Kamali, P., Kothari, S., & Muir, D., The Price of De-Risking—Reshoring, Friend-Shoring, and Fragmentation.

IMF. (2024, May 7). Gopinath, G., Geopolitics and its impact on global trade and the dollar (speech).

NetSecCloud. (2024, Oct. 23). Star vs. Mesh: Choosing the Right Network Topology for Your Business.

OECD. (2024, Sept.). Education at a Glance 2024.

OECD. (2024, Nov.). Promoting resilience and preparedness in supply chains (Trade Policy Paper No. 286).

OECD. (2024, Apr. 23). Offshoring, reshoring and the evolving geography of jobs.

OECD. (2025, Mar. 12). What are the key trends in international student mobility? (Education Indicators in Focus #88).

Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). (2024, Sept. 26). De-risking charts the path to decoupling.

Reuters. (2025, Aug. 5). US trade gap skids to 2-year low; tariffs exert pressure on service sector.

US Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. (2024–2025). Monthly Treasury Statement (various).

US Department of Commerce, USTR. (2025). Mexico—United States Trade Representative: Country facts (2024 totals).

WTO. (2024, Apr.). Global Trade Outlook and Statistics — April 2024.

WTO. (2024, Oct. 10). Global goods trade on track for gradual recovery despite headwinds (Updated forecast).

WTO. (2024, Dec. 13). Merchandise trade continues to expand in Q3 2024 (news release).

World Trade Organization (WTO). (2024). World Trade Statistics 2024.

Comment