Hold the Ladder, Don’t Pull the Rung: Why Income-Secure Schooling—Not Wage Quotas—Will Break the Immigrant Poverty Trap

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Urgent Action Needed: One in four non-EU youths across the EU are early leavers from education and training, compared to just 8% of nationals. This significant gap, which has a far greater impact on long-term earnings than debates over 'wage discrimination', is a pressing issue that demands immediate attention. The best contemporary employer–employee evidence shows that by the second generation, once young people make it through school and into comparable jobs, adjusted wage gaps essentially vanish. The remaining gap is primarily an age and experience deficit, not a pay penalty for their background. The uncomfortable truth is that we are losing potential nurses, coders, and millwrights before they finish upper-secondary, often because families hovering just above the poverty line need every adolescent hour to pay rent or remit support. If we want a larger, better-trained workforce, the most efficient “labour-market policy” is not at the factory gate; it’s a guarantee that schooling time is income-secure for low-income immigrant households. The measure of our seriousness is whether we finance that time.

Reframing the Problem: From Pay Penalties to Time Poverty

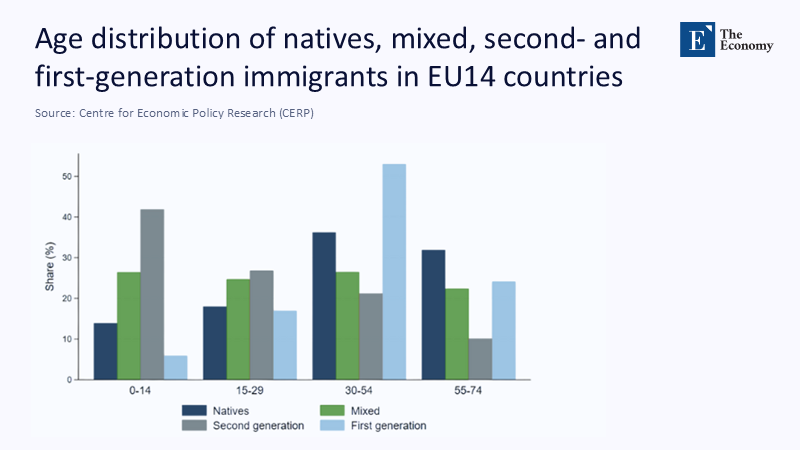

We have spent years arguing over whether second-generation workers are paid less because of their background. A better reading of the freshest cross-European data is simpler and, in policy terms, more radical: the binding constraint is time—time to master the language of instruction, to complete upper-secondary, to accumulate early work experience that compounds. Recent Europe-wide assessments show second-generation employment rates lagging natives (with cross-country variation), pointing to entry and progression frictions rather than systematic pay cuts within similar jobs. Complementary analyses of intergenerational mobility across 15 destination countries report the same pattern: significant first-generation income gaps that shrink markedly in the second generation—yet not uniformly nor automatically.

These findings demand a significant policy turn. If families just above the poverty line depend on teen earnings, educational persistence competes with household cash flow. Classic anti-discrimination toolkits—audits and sanctions—remain necessary for fair hiring, but they won’t solve a liquidity problem inside the household. What will: guaranteed income support that protects study time, paired with school-to-work bridges that let adolescents earn without exiting education.

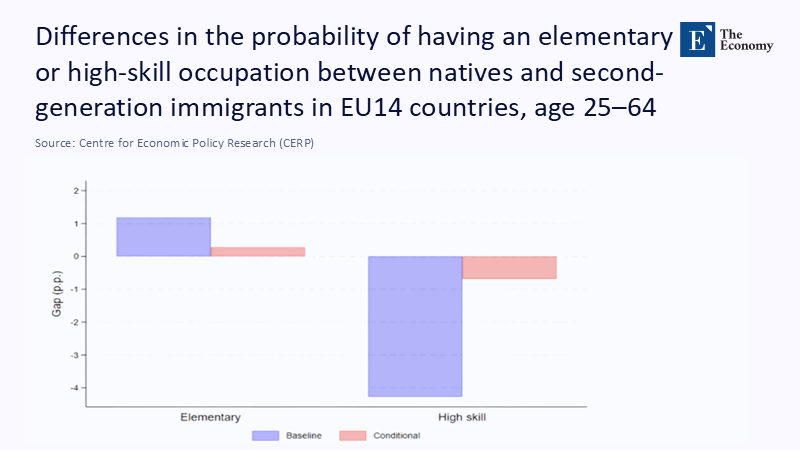

What the Newest Wage Evidence Says

A granular Belgian employer–employee study—1.3 million observations across 1999–2016—offers a rare, rigorous look at wage setting inside firms. After controlling for age, tenure, education, contract type, occupation, and firm fixed effects, it finds a 2.7% adjusted wage gap for first-generation workers from developing countries, but no adjusted wage gap for their second-generation peers. The authors go further with reweighted recentered-influence-function (RIF-OB) decompositions. This sensitivity strategy traces wage differences along the distribution—not just at the mean—and separates composition effects (who works where) from wage-structure effects (how similar workers are paid). For second-generation workers, those decompositions show that overall gaps are almost entirely explained by being younger and having less tenure, not by a residual pay penalty.

Critically, the robustness checks matter: the results withstand alternative sector controls when firm dummies cannot be included in quantile decompositions, with bootstrap errors reported to gauge the quality of counterfactual identification and specification. In plain terms: when we hold job and workplace constant and probe the distribution with modern tools, the second generation’s wage story is about experience accumulation, not discrimination in pay. That is the fulcrum for policy.

The Bottleneck We Refuse to Fund: Early Exits and Under-employment

If wage parity emerges conditional on finishing school and entering comparable jobs, what keeps too many second-generation youths from reaching that point? Start with the education pipeline. In 2024, early leaving rates among non-nationals were nearly three times those of nationals in the EU. Language gaps, of course, matter; OECD tracking highlights the need for systematic language assessment and targeted support. But a second, often ignored barrier is the household cash constraint. At the margin, families just above the social-assistance line rely on teen earnings for basic needs, especially where part-time service jobs are abundant and part-time rates are highest among non-EU citizens.

The labour market backdrop has been relatively favourable—EU-wide employment near 76% and slack falling through late-2024—yet the benefits accrue unevenly without targeted supports. And where education is attained, we still waste skills: 39% of employed non-EU degree-holders were over-qualified in 2022, a significant productivity loss that slows experience-wage compounding for immigrant households as a whole. The through-line is clear: without income-secure schooling and transition programs that pay, the second generation continues to arrive late to the wage ladder.

Implications for Classrooms, Campuses, and HR Offices

Educators see the trade-offs first. Attendance dips clustered around payday. Students juggle care duties and late shifts. Language proficiency stagnates when schooling stops. OECD’s Education at a Glance 2024 synthesis is decisive on the macro point: equity and quality travel together—systems that protect access for disadvantaged students also deliver stronger overall outcomes for schools, which translates to front-loaded language support, extended-day tutoring, and credit-bearing work-based learning that pays enough to displace low-skill jobs, which otherwise cannibalize homework time.

For administrators and HR leaders, the wage evidence suggests a pivot from “closing pay gaps” in the abstract to accelerating tenure and task progression in practice. Structured early progression ladders, paid micro-internships during upper-secondary, and a bias toward recognizing prior learning can compress the early-career experience gap that the Belgian study shows explains so much of the wage difference for the second generation. In short: speed up the first two rungs of the ladder, and parity follows almost mechanically.

Addressing the Obvious Critiques

“Isn’t discrimination still pervasive?” In hiring, yes: audit studies continue to find callback penalties by name and origin. But once inside firms and controlling for job and workplace, the second generation’s pay looks strikingly like natives’ pay; the Belgian decompositions show no statistically significant wage-structure effect for second-generation men and women across the distribution. “Averages hide outliers.” True. The same study notes heterogeneity by origin: adjusted results cluster around parity for second-generation workers from several regions, with small positives or zeros, while first-generation gaps persist—consistent with human-capital transferability challenges and sectoral sorting. “What about gender?” A separate, durable gender pay gap remains (about 7–8% adjusted in the same data), reminding us that integration and gender equity are distinct, intersecting agendas that both require policy muscle.

Finally, EU-wide surveillance confirms that employment gaps for the second generation persist in some countries—again pointing to entry frictions and education-to-work transitions rather than within-job pay penalties. That’s why an “income-secure schooling” strategy complements, rather than replaces, anti-discrimination enforcement and employer DEI work.

What Government Can Do When Every Adolescent Hour Pays a Bill

The policy lever is not complicated; it is politically hard because it moves money. First, guarantee income-secure schooling for low-income immigrant households just above the benefit threshold: a means-tested learning income for 15–19-year-olds tied to full-time enrollment and attendance, calibrated to replace typical part-time wages in retail or hospitality. Second, fund credit-bearing, paid work-based learning in shortage fields so families don’t have to choose between earnings and school—a design consistent with high employment. In these low slack conditions, employers struggle to staff apprenticeships. Third, embed language acceleration as a default entitlement in lower-secondary, paired with short, paid micro-internships that match emerging language proficiency with real tasks; OECD guidance remains clear on the payoff to early language support. Fourth, attack brain waste head-on to improve household income expectations: recognize foreign credentials faster and subsidize bridge training; the over-qualification rate among non-EU graduates shows the scale of the prize. Finally, focus on predictable pinch points for second-generation women—childcare for younger siblings and scheduling flexibility—to narrow the gendered exposure to part-time roles that Eurostat shows are disproportionately borne by non-EU households. In a tight labour market, these are not social programs alone; they are workforce investments.

Financing Time: The Missing Ingredient in Integration

Across Europe in 2024–2025, the data tell a coherent story. Labour markets are relatively strong. Employers are hiring. And when second-generation young people complete their education and enter comparable jobs, their pay looks like pay for everyone else. The problem is upstream: too many leave school early because their families cannot afford the luxury of adolescent study time, and those who stay too often step into under-skilled roles that slow tenure and wage growth. (Eurostat and OECD evidence; Belgian decompositions on age/tenure.

If we want to absorb the second generation’s talent—on its merits and at scale—stop obsessing over abstract wage gaps and pay for the time that turns language acquisition into credentials and credentials into tenure. Do that with a learning income, paid pathways, and language-first supports that make school the dominant “job” of adolescence for low-income immigrant households. Everything else—fair-hiring enforcement, credential recognition, early progression ladders—follows. This is not charity; it is the cheapest way to create the skilled, tax-paying workforce we say we need. The ladder is already sturdy. Our task is to hold the rung long enough for the second generation to climb.

The original article was authored by Tommaso Frattini and Gabriele Cugini. The English version of the article, titled "The labour market disparities of second-generation immigrants," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Abramitzky, R., Boustan, L., Jácome, E., & Pérez, S. (2021). Intergenerational mobility of immigrants in the United States over two centuries. American Economic Review, 111(2), 580–608.

CaixaBank Research. (2025). A changing European labour market: the role of immigration and non-EU workers. (Research Focus, June).

CEPR VoxEU. (2025). Intergenerational mobility of immigrants in 15 destination countries. (Column, April).

Frattini, T., & Cugini, G. (2025). The labour market disparities of second-generation immigrants. CEPR VoxEU, July 30.

Migration Policy Institute. (2024). How Immigrants and Their U.S.-Born Children Fit into the Future Labor Market. (Report, March).

OECD. (2024). Education at a Glance 2024: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2024–2025). Students from migrant backgrounds (topic hub) and Review education policies: Migrant background.

Pineda-Hernández, K., Rycx, F., & Volral, M. (2022). Moving up the Social Ladder? Wages of First- and Second-Generation Immigrants from Developing Countries. IZA Discussion Paper No. 15770. (See also 2024 journal version in Journal of Economic Inequality.)

Eurostat. (2023). Migration 2023 – Overqualification of migrants (interactive publication).

Eurostat. (2024). Migrant integration statistics – socio-economic situation of young people (Statistics Explained).

Eurostat. (2024–2025). Migrant integration statistics – labour market indicators; employment conditions; part-time news release (July 23, 2025).

Comment