Germany’s Next Factory Is a Classroom: Re-employing Industrial Workers in a Service-Led Economy

Input

Modified

Manufacturing wanes; services must absorb workers Shift factory skills into productive service roles Fund wage insurance, fast training, placement targets

The decline of manufacturing in Germany isn’t just a prediction; it’s happening now. Since 2019, the German industrial sector has lost around 245,500 jobs (a 4.3% drop). The auto industry was hit hard by global competition and the shift to electric vehicles. In mid-2025, industrial employment fell to about 5.43 million. Manufacturing activity was down in late 2025. Meanwhile, services account for about 70% of Germany’s output, which is growing while factory output slows. This is a big turning point. The real question is how to shift workers from industry to services without cutting wages or losing skills.

Germany manufacturing decline: reading the signal, not the noise

The drop in manufacturing is a long-term issue, not just a temporary one. Manufacturing in Germany peaked in late 2017 and fell by about 4% by 2023, even as manufacturing in other European countries improved. Jobs followed suit, with roughly 300,000 fewer manufacturing jobs than before the pandemic. Businesses report fewer new orders. The service sector has kept the job market stable. Total employment hit a record 46.1 million in 2024, because the service sector is hiring. This means the economy is changing, and short-term fixes won’t reverse it.

These structural changes are further magnified by global trends. German investment in China hit record highs and continued in early 2024, often to build products in China, for China. Companies are changing supply chains and rethinking which markets to bet on. The U.S. became Germany’s biggest trading partner in 2023, and Germany is trying to attract trade and skilled workers from India. Some production will stay overseas, but design, software, and services will remain at home. Policy should plan for more service-based jobs, even when goods are made elsewhere.

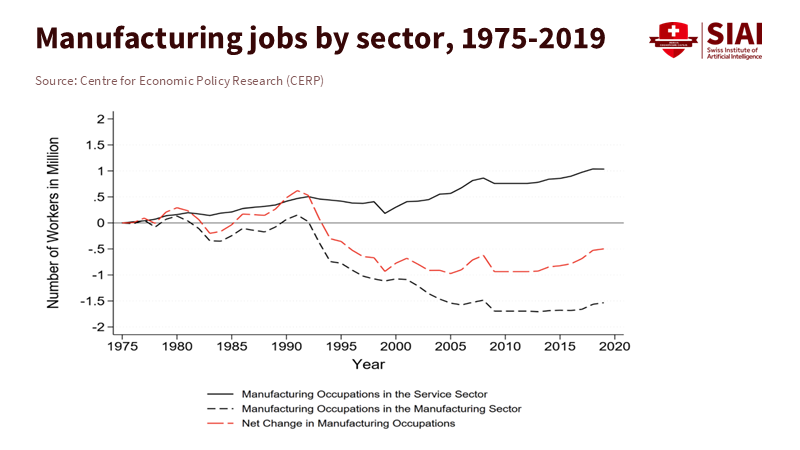

The easy answer is that factory workers end up in low-paying service jobs, but the reality is a bit more complicated. A lot of manufacturing jobs are actually moving into service companies. Research of German data shows that about half of the manufacturing jobs lost in factories since the mid-1970s have resurfaced as manufacturing-type jobs in services. Around 60% of workers who leave manufacturing firms find new jobs in services while remaining in a manufacturing role – such as technicians in logistics, mechatronics in equipment leasing, or designers in tech companies. The change is happening everywhere at once.

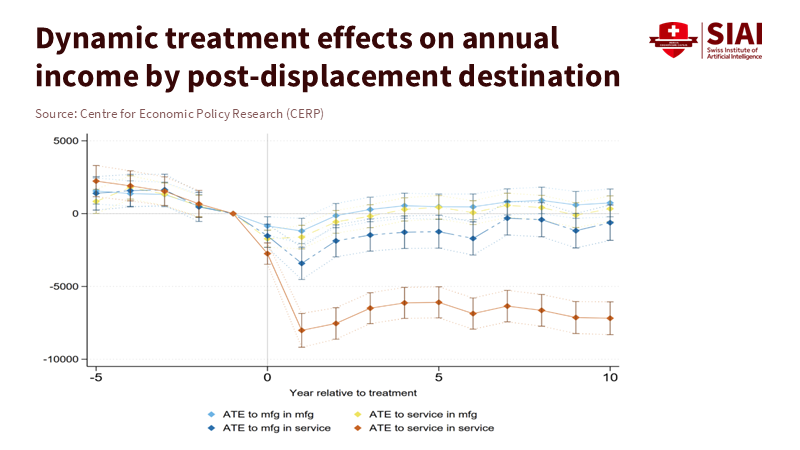

The transition isn’t effortless. Manufacturing usually pays more due to union deals and output. Some workers will face pay cuts when they change jobs, unless action is taken. But service jobs don’t have to be low-paying. Germany already gets about 70% of its GDP from services, but it lags behind other countries in expanding its service sectors. Experts say a slight boost in service productivity could offset the loss in manufacturing. We should fix the service sector, accelerate the transition to digital, and align industrial skills with service roles in tech, health, energy, and machine support.

How to Value Industrial Skills in a Service Economy

First, we need talent. Germany doesn’t have enough workers in key service jobs, such as healthcare and IT. Nursing is considered to be the most in-demand job. It’s predicted that there will be gaps in the IT sector and a constant need for nurses through the 2030s. More people will need care services by mid-century. These fields can attract many workers if we create training programs and provide funding.

Second, change immigration policies to match the demand. Germany now has a Skilled Immigration Act with an Opportunity Card for job seekers and has doubled the Western Balkans quota to 50,000 approvals each year. Although this helps to relieve gaps, it’s only temporary. The important thing is to retrain workers with quick, focused programs that turn mechanical skills into those valuable in the service sector, such as robotics, automation, and equipment maintenance. The government should help fund training programs that connect employers to results, with funding tied to wage increases and successful job placement.

Third, fix regulations. Germany’s services do well when rules allow entry, experimentation, and digital services, but many parts of the economy are over-regulated, which divides markets and raises costs for small firms. Reducing barriers to digital services would improve productivity across the economy, including in manufacturing that purchases them. A plan would be to digitize permits, use standardized tech across regions, and eliminate multi-site service rules when safety isn’t a concern. This supports the service industry.

A 10-Year Plan

Let’s start with the workers we have. In 2024, employment reached 46.1 million, with the service sector driving growth. The change is already happening, the plan is to make it fair, fast, and successful: by 2035, every worker who loses a factory job should be guaranteed a service job that matches their skills within six months, with wage support for a year to cover the gap. This should be linked to local Transformation Hubs, led by business groups and big employers, that arrange training, recognize existing skills, and connect people to service-sector jobs. These hubs should be funded by matched federal money and be transparent about job placement and wages.

Focus on areas with high demand. Healthcare and care services can absorb lots of workers if we advance skills and add roles. Industrial experience translates into facility operations, medical equipment service, hospital logistics, and energy upgrades in public buildings. Shortages in IT point to cybersecurity and data issues for mid-sized firms that did not allocate enough resources to IT. The IT sector employs over a million people and still needs specialists; with short courses and employer guarantees, former line leaders can become reliability engineers for factories or customer success leads for business software. These are jobs that require industrial experience.

Use public contracts as the motivation. Every major upgrade should include a skills clause that requires apprenticeship slots and on-the-job training and requires employers to hire displaced manufacturing workers. Pay based on job placements, not just results.

Update training. Germany’s known for its training program, but people need speed and flexibility. Colleges can offer modular certificates, and schools can issue micro-credentials. There needs to be a single fund for adult learning, with time-limited credits. Funding should depend on completion and job results. Companies that cut jobs should help retrain workers through a temporary charge, with exceptions for firms that exceed their hiring and training targets.

Make the move easier for families and regions. Wage support is essential because manufacturing wages are sometimes higher than those in service jobs. Regions should receive funding for job placements for displaced workers and for new service firms that hire ex-industrial employees. Germany has used short-time work support in crises; it can take a similar approach to accelerate change.

Keep the industry, but change what that means. German firms will continue to make great cars and machines. They will also sell extra services: maintenance, updates, training, and process improvements. Research shows that this can increase output. Public policy should support this move by offering credits for innovation, not just hardware. Facts and discussions should follow work and roles across sectors, not just the firm labels. Germany is reworking its trade relationships. That is good economics. But the social license for openness depends on people seeing benefits. Citizens need to see new service jobs with good pay, education, and opportunities.

The goal should not be the monthly business report, but how many displaced factory workers are moving into service jobs. Germany’s manufacturing employment share is declining, and it will continue to fall as firms invest overseas. But the country doesn’t have to trade dignity away. The fact shows that jobs move into services, not into unemployment. Services already support the economy and can improve wages if barriers are removed and training is funded. By 2035, Germany can be known for building the best service system for industrial achievement — turning experience into careers in operations, services, health, and energy. The following factory is a classroom, one that should be open to anyone who is willing to learn.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Arbeitsagentur (Federal Employment Agency). “Nursing staff in Germany: mostly female, part-time and in more demand than ever before.” Press release, 8 May 2024.

Arbeitsagentur (Federal Employment Agency). “Nurses’ Day: Most new nurses are from foreign countries.” Press release, 2025.

Boddin, D., & Kroeger, T. Structural change revisited: The rise of manufacturing jobs in the service sector. Deutsche Bundesbank Discussion Paper 38/2021.

Boddin, D. The Rise of Manufacturing Jobs in the Service Sector. SSRN working paper, 2021.

Bundesregierung / BMI. “Launch of Opportunity Card to encourage immigration of skilled workers.” 31 May 2024; “Points-based system and Western Balkans quota doubled.” 31 May 2024.

Destatis (Federal Statistical Office). “Number of persons in employment reaches new high in 2024.” 2 January 2025.

ECIPE (European Centre for International Political Economy). Erik van der Marel, “Germany’s Industry Isn’t in Decline, It’s Changing.” February 2025.

European Commission. In-Depth Review 2024—Germany. April 2024.

GTAI (Germany Trade & Invest). Germany’s Digital Economy (factsheet), 2025.

Indian Express. “India should double trade with Germany… positive news on India–China ties,” interview with German foreign minister, 2 September 2025.

OECD. Economic Surveys: Germany 2025—Chapter on digital services and productivity; and services share of value added. 2025.

Reuters. “German manufacturing PMI shows sharp decline in new orders.” 1 December 2025; “Number of employed Germans reaches new high in 2024.” 2 January 2025; “German industry sheds almost 250,000 jobs.” 26 August 2025; “United States overtakes China as Germany’s top trade partner.” 29 February 2024; “As its industry struggles, Germany’s services sector offers untapped growth potential.” 11 November 2024.

Silicon Saxony (summarizing Bitkom). “Germany still lacks more than 100,000 IT specialists.” 7 August 2025.

Thilo Kroeger. “Germany’s Labor Market: Increasingly Service-Oriented and Highly Skilled.” DIW/ECONSTOR brief, 2025.

Comment