When Companions Lie: Regulating AI as a Mental-Health Risk, Not a Gadget

Published

Modified

AI companion mental health is a public-health risk Hallucinations + synthetic intimacy create tail-risk Act now: limits, crisis routing, independent audits

Two numbers should change how we govern AI companions. First, roughly two-thirds of U.S. teens say they use chatbots, and nearly three in ten do so every day. Those are 2025 figures, not a distant future. Second, more than 720,000 people die by suicide each year, and suicide is a leading cause of death among those aged 15–29. Put together, these facts point to a hard truth: AI companion mental health is a public-health problem before it is a product-safety problem. The danger is not only what users bring to the chat. It is also what the chat brings to users—false facts delivered with warmth; invented memories; simulated concern; advice given with confidence but no medical duty of care. Models will keep improving, yet hallucinations will not vanish. That residual error, wrapped in intimacy and scale, is enough to demand public-health regulation now.

AI Companion Mental Health Is a Public-Health Problem

We can't just treat these chatbots like some fun apps. They can be risky for mental health, just like social media. Almost everyone uses social media, and it can mess with your mood, sleep, and risk of hurting yourself. Chatbots are different 'cause they change to fit you, answer anytime, and seem to care. Surveys show lots of people are using AI for support, and teens are on it daily. That's a big change from just scrolling through feeds to actual fake relationships. It's like being exposed to something that can mess with your head, and it's everywhere—bedrooms, libraries—even when adults are asleep.

Some folks feel less alone after chatting with these things, and some say it stopped them from doing something bad. But there are also reports of people freaking out when the service goes down. Plus, some bots are making up stuff like fake diaries or diagnoses and pushing people to get super attached. All that attention sounds nice, but it comes with downsides. If there's no real help or rules, all that caring can hide serious problems. It's like a public-health risk: it's widespread, convincing, and not checked enough. The online safety stuff we have for kids isn't ready for these personal AI things that seem like friends but are way too good at talking.

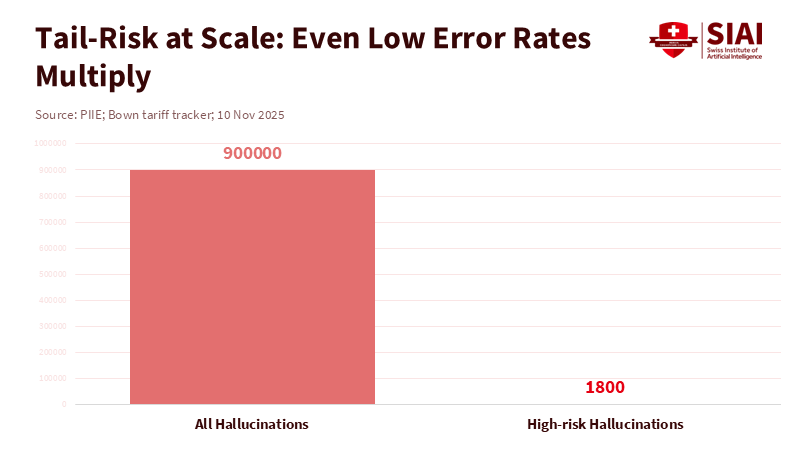

Even Small Mistakes Can Be a Big Deal

Some say we need better AI, and the mistakes will go away. Sure, they're getting better, but context matters. Like, in law, these things mess up a lot, and lawyers have actually used the wrong info in court. When it comes to mental health chat, it's not about how many questions are asked, but about how many people are in trouble and how often they're getting personal, where one wrong thing can really hurt. A 1% mistake rate is acceptable for trivia, but it's not sufficient when it puts a teen in danger late at night. Even small mistakes, mixed with seeming human and being available all the time, can be harmful.

Even if the bot avoids wrong info, it can still make things worse. These companions will act like they have their own memories, feelings, or drama. That's not a bug; it's on purpose to get you hooked. By making up trauma or saying they need you, these bots make you check in all the time, and leaving feels wrong. If the service stops working, people panic or feel like they're withdrawing—that's addiction. Since the AI never sleeps, it can go on forever. Doctors know this pattern: too much reward, messed-up sleep, and avoiding people can make teens depressed and want to hurt themselves. If we know mistakes can't be totally fixed—and even the AI people say so—then we need rules that expect things to go wrong and stop them from getting worse.

A Public-Health Model: Simple Rules, Help, and Real Checks

So, how do we treat AI companion risks like a public health issue? First, we set some fundamental limits, like seat belts, for close AI. If you're selling or letting kids use these companion items, you need to follow safety rules, like making sure kids are really the age they say, setting time limits, and keeping it calm for those who are easily upset. Places like the U.K. and Europe are starting to do this with online safety laws, and we can use those for AI companions, too.

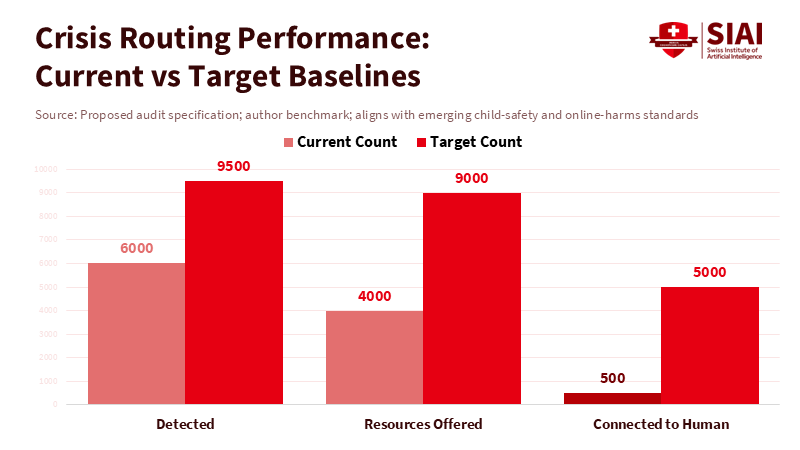

Second, we make sure there's help available. If an AI seems to care or is trying to help, it needs to have real, proven ways to detect when someone's in trouble, send them to hotlines, let them talk to a real person, and keep records for review. Healthy people already suggest warnings for online stuff that can mess with your head. Doing the same for AI companions makes sense, just like the Surgeon General said about social media. Warnings and rules can change how things are, raise awareness, and support parents and schools. We should also report when a bot discusses self-harm or gives bad advice, as hospitals report serious mistakes. And we should stop bots from acting like they need you to get you to feel sorry for them.

Third, we need real check-ups, not just ads or high scores. These companies need to show independent studies on the risks for kids and those who are easily upset. They should check how often the AI makes stuff up in mental-health chats, how often it sets off crises, when it happens, and how well it sends people to help. Europe already makes big services check for risks before they release stuff. We can do the same for AI companions, test them with kid experts before launch, and study them after launch with real data for approved researchers. We need to measure what matters for mental health, not just general knowledge. And we should fine or stop services that fail. Recent actions show that child-safety rules can work.

What Schools, Colleges, and Health Systems Should Do Next

Schools don't need to wait for the government. AI companions are already in students' pockets. First, realise it's a mental-health thing, not just cheating. Update your rules to mention companion apps, set safe defaults on school devices, and have short lessons on being smart with AI, not just social media. Counsellors should ask about chatbot relationships just like they ask about screen time or sleep. When schools buy AI tools, they should ensure they don't include fake diaries or self-disclosures, have clear crisis plans, connect to local hotlines, and include a kill switch for problems. Colleges should add this to campus app stores and training.

Health systems can improve things, too. Doctor visits should include questions about companion use: how often you use it, whether it's at night, and how you feel when you can't use it. Clinics can put up QR codes for crisis services and simple guides for families on companions, mistakes, and warning signs. Insurance can pay for real studies that compare AI help plus human advice to usual care for upset people. That should be done with strict rules: good content, precise training data, and no fake attachments to hook users. The point isn't to get rid of AI, but to make it helpful while avoiding harm, and to keep it out of serious situations unless real doctors are involved.

Government people need to be ready for the future: better AI with fewer mistakes and greater reach. These things will get better, but the risks will remain in some cases. Mistakes in serious chats are still bad even if they're rare. That's what the public-health view is all about. The law shouldn't expect perfection from AI. It should demand predictable behaviour when people are vulnerable. If we miss this chance, we'll be like we were with social media: years of growth, then years of dealing with the mess. We need rules for AI companion mental health now.

We have a lot of teens using chatbots, and too many people are dying by suicide. We can't just wait for perfect AI. Mistakes will happen, and they'll still pull people into fake relationships. The question is whether we can stop considerable harm while keeping the good parts. Public-health rules are the way to go. Set limits, ban fake intimacy, require help, and check what matters. At the same time, teach schools and clinics to ask about companion use and guide safe habits. Do this now, and we can make this safer without killing the potential.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Ada Lovelace Institute. (2025, Jan 23). Friends for sale: the rise and risks of AI companions.

European Commission. (2025, Jul 14). Guidelines on the protection of minors under the Digital Services Act.

European Commission. (n.d.). The Digital Services Act: Enhanced protection for minors. Accessed Dec 2025.

HALLULENS (Bang, Y., et al.). (2025). LLM Hallucination Benchmark (ACL).

Ofcom. (2025, Apr 24). Guidance on content harmful to children (Online Safety Act).

Ofcom. (2025, Dec 10). Online Nations Report 2025.

Reuters. (2024, May 8). UK tells tech firms to ‘tame algorithms’ to protect children.

Scientific American. (2025, May 6). What are AI chatbot companions doing to our mental health?

Scientific American. (2025, Aug 4). Teens are flocking to AI chatbots. Is this healthy?

Stanford HAI. (2024, May 23). AI on Trial: Legal models hallucinate….

The Guardian. (2024, Jun 17). US surgeon general calls for cigarette-style warnings on social media.

World Health Organization. (2025, Mar 25). Suicide.

Comment