China's iron ore strategy has become a key battleground in the U.S.-China resource conflict

Input

Modified

China centralizes iron ore power Simandou adds leverage and options Train procurement to protect budgets

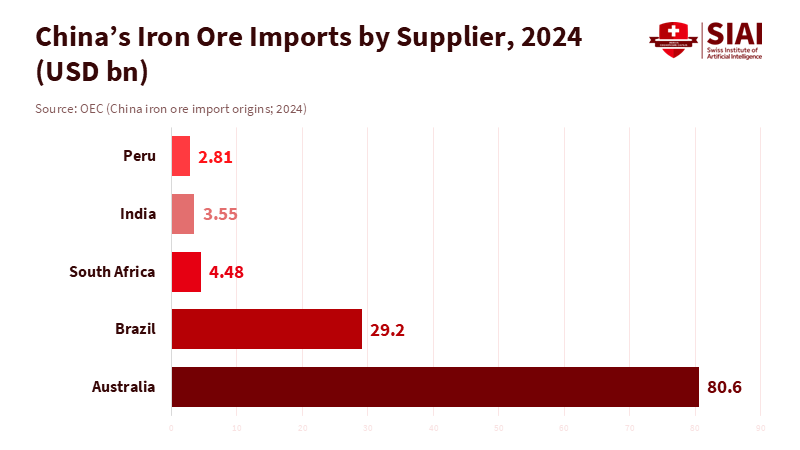

In late 2025, China, which accounts for almost three-quarters of the world's seaborne iron ore trade, showed its strength. China Mineral Resources Group, their new state-backed buyer, told steel plants to stop buying specific shipments from BHP while they talked about contracts. At the same time, shipments from Guinea's Simandou mine, backed by China, started arriving. These actions might not have been big news, but they really changed prices, bargaining power, and plans. The U.S.-China resource conflict is now focused on basic materials, which will affect economic costs, and not just high-tech stuff. Last year, China's imports hit a record 1.24 billion tons, so buying as a group is a powerful tactic that Beijing is using.

How the U.S.-China resource conflict moved to basic goods

The U.S.-China resource conflict began in high tech. The U.S. limited chip exports; China restricted the export of gallium and graphite. These are crucial for supply chains. Iron ore, though basic, is key for steel, cars, infrastructure, and defense. In 2024, the U.S. raised tariffs on Chinese goods, including minerals and metals. China then limited graphite and chip-metal exports. The outcome: resource policy is now security policy—including basic materials, where China’s size matters.

China's state buyer, created in 2022 to purchase iron ore in bulk, is the key. By telling steel plants and traders to stop buying specific BHP products when negotiating contracts in 2025, they not only tightened supply for a short time but also tested whether a single buyer could change the usual price. At the same time, Chinese-backed groups started shipping ore from Simandou in November 2025. This gave them another option besides Australia and Brazil in the long run. These two things – one short-term and one long-term – suggest a big change: Beijing is going from accepting prices to setting them for these materials. This will influence the U.S.-China resource conflict for the years to come.

Buying in bulk: CMRG, Simandou, and getting to be the price leader

First, let's talk about how it works. China Mineral Resources Group (CMRG) was created in 2022 with government support to coordinate purchases for China's biggest steel companies. In 2025, it demonstrated its strength by halting specific BHP shipments during contract negotiations. They clearly wanted better deals and to set the price. This isn't a boycott, but a way to bargain when you're really big. When a buyer that already purchases most of the world's iron ore that’s transported by sea acts as one, miners need to respond – not only to price formulas, but also to the quality of shipments, scheduling, and credit terms. That's how you become a leader.

Simandou is still the only source that can soon compete with Australia and Brazil. Shipments started in November 2025, and people expect production to increase through the late 2020s. The high-quality ore from Guinea reduces steel emissions, gives options for mixing, and is a good alternative to the Australian supply. With China importing record amounts and Simandou being available, buying in bulk can change trade flows. Even small changes can affect prices in tight markets.

From buyer to rule maker: what a Stackelberg leader looks like

In theory, when one buyer is enormous in a market, they can narrow the price range by coordinating demand. In reality, a buyer as big as China can set expectations first, let suppliers react, and then make minor adjustments with specific purchases. CMRG's order to stop specific mixes during talks was a real-world example. It showed they were willing to adjust their mix preferences and shipment timing until miners agreed on issues such as price terms, impurity penalties, and delivery schedules. This turns price discovery on its head, shifting it from the seller to the buyer.

Prices show what's happening. The usual 62% Fe fines traded at $100–$110 per ton through late 2025, even as China's steel production fell and exports rose significantly. Stable prices with lower production support, organized group buying, and buying when prices go down. With supplies coming from Simandou and a system to license Chinese steel starting in January 2026, the market allows Beijing to smooth domestic cycles while influencing global prices. So, the U.S.-China resource conflict isn't just about rare metals, but about who sets the rules for basic materials that affect industry costs.

What this means for education: updating skills for the U.S.-China resource conflict

Education leaders can't think this is just geopolitics far away. When one buyer affects iron ore prices, it impacts construction, vehicles, appliances, and other purchases. Business schools, policy programs, and vocational colleges should consider commodity market design and group purchasing as essential skills. Students need to learn how state buyers adjust prices, how new mines like Simandou shift trade, and how controls affect supply chains. These skills are essential for planning and training the workforce.

Curricula should include three lessons. First, data skills are key: follow indicators – Chinese import amounts, port stocks, prices, and policy changes – because choices often depend on these numbers. Second, people need to better understand government purchasing. District and university buyers should understand long-term contracts and hedging to secure materials when market conditions are favorable. Third, scenario planning should be part of courses and training. If Simandou grows quickly, Australian fines might be discounted. If tariffs increase, bringing production back home will stress budgets. If Chinese steel exports face licensing limits in 2026, imported steel prices might rise. Educators are in the best position to prepare analysts and public purchasers for what's coming. They should get ready for the future, not the present. The policy results are even bigger. U.S. agencies that fund infrastructure need expertise in commodity markets, not just grants. State governments should connect workforce programs to this change, integrating metallurgy, logistics, data, and trade law. In Asia and Europe, governments should prepare for tighter profits as Chinese buying and new African supply reshape prices. Scholarships and short courses can target professionals in public purchasing, with projects that simulate a buyer negotiating with miners while managing climate concerns. This is training for a resource conflict fought with spreadsheets and sanctions.

There will be resistance. Some will say that organizations can't beat geology, and Australia and Brazil will always be on top. But Simandou's shipments show that infrastructure and finance can shift things. Others warn that price controls invite retaliation. But a lot of this is organizing – aligning fragmented demand with strategy. The U.S. and its allies will respond with tariffs, local projects, and stockpiles, which will change trade but not remove the advantage of a dominant buyer.

The biggest question is whether this power will last. It will, as long as China continues to import a lot and groups like CMRG stay focused. Data shows that China still accounts for about half of the world's crude steel output, despite changes in output. This production drives import demand, strengthening buyer power. If domestic demand weakens, group purchasing can still smooth cycles by timing purchases and using inventory. If demand strengthens, Simandou's growth can cushion the impact on prices. The system Beijing is building is self-strengthening: unified buying leads to better deals, and better deals make the system even more valuable.

To repeat the main point: one country makes up about three-quarters of the iron ore that's transported by sea. This is the main event of the U.S.-China resource conflict. We shouldn't oversimplify this as just bans and bravado. It's a quiet competition over who can turn size into rules and logistics into power. China’s iron ore strategy – group purchasing with new supply – shows one way to get price leadership in basic materials. If educators, administrators, and policymakers want to protect budgets and encourage growth, they must prepare people who can understand and act on this situation. The message is clear: understand the market, develop talent, and negotiate as a system – because the other side is already doing it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AXSMarine. (2025, Oct. 15). Iron ore flows in 2025: Top importers and production by route.

CME Group. (2025). Iron Ore 62% Fe, CFR China (Platts) average price option – Quotes.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Dec. 12). China moves to regain iron ore market power.

GMK Center. (2025, Dec. 10). China Mineral Resources Group criticized the situation on the iron ore market.

Hellenic Shipping News. (2025, Dec.). Commencement of operations at the Simandou mine unlocks a new era of long-haul iron ore flows.

Investing.com. (2025). Iron ore fines 62% Fe CFR futures – historical data.

Reuters. (2024, May 14). Biden sharply hikes U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports, including critical minerals.

Reuters. (2023, Oct. 20). China to require export permits for some graphite products.

Reuters. (2023, Jul. 3/10/19). China restricts exports of gallium and germanium products; exports plunge after curbs.

Reuters. (2025, Oct. 10). China’s state iron ore buyer offers BHP cargoes for sale amid ban fears.

Reuters. (2025, Nov. 20–21). Stand-off between China’s iron ore buyer and BHP; China expands BHP iron ore ban to new product.

Rio Tinto. (2025). Simandou project update and first shipment timeline.

ThinkChina. (2025, Nov./Dec.). How China unlocked Simandou; The African mine that could reshape trade; and China’s iron ore imports rise to 1.24 billion tons in 2024.

World Steel Association. (2025, Nov. 21). October 2025 crude steel production.

Comment