Pricing the Quiet Quake: Rebuilding Risk, Not Debt, with Disaster Recovery Financing

Input

Modified

Moderate quakes cause deep, unpriced losses through financing gaps Price mid-risk and pre-fund rapid recovery with layered instruments Trigger cash to schools to cut spreads and speed rebuilding

Earthquakes are a relentless drain on economies, not rare, dramatic shocks. The world now spends about $202 billion a year on visible earthquake damage. When lost schooling, broken supply chains, health impacts, and ecosystem losses are included, the bill soars above $2.3 trillion—nearly ten times the official tally. For countries with limited budgets, this persistent wealth leak shows up as slower growth, wider spreads, and hard choices for classrooms and clinics. The real paradox: so-called “moderate” earthquakes inflict the worst harm where states lack rapid, targeted recovery funding. The case is clear—invest in early-stage disaster recovery financing to reduce long-term costs and protect schools, economies, and future growth.

Why We Need to Include Moderate Earthquakes in Disaster Relief Plans

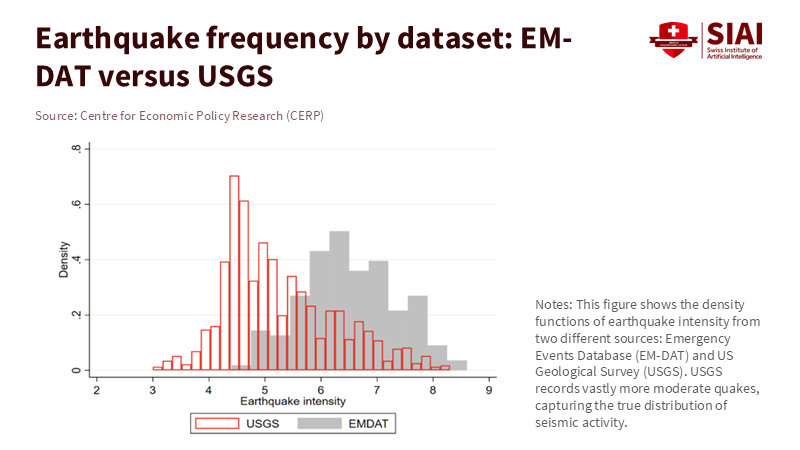

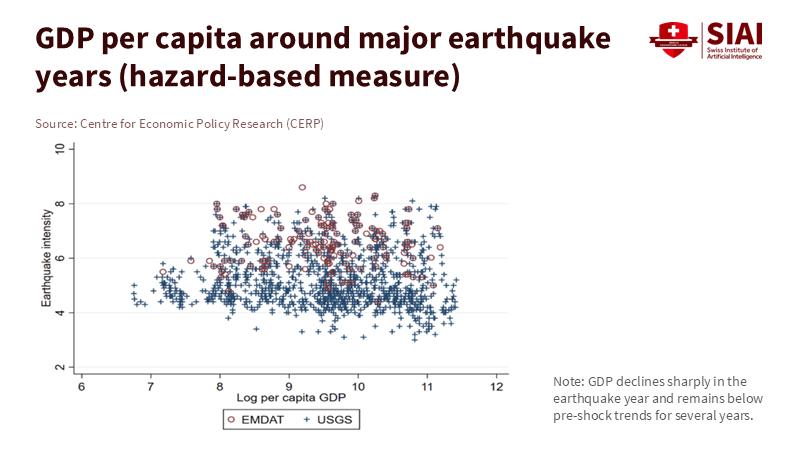

According to recent studies, it’s not just those mega-earthquakes that mess with the economy. When you look at all earthquake data, not just the ones big enough to make headlines, you see a pattern. Per capita GDP drops in the year of a quake and stays low for years, mostly in poorer countries. Richer countries can handle it better because they have stronger building codes, better insurance, and greater access to credit. It turns out that what looked like a return to normal in past studies was just due to incomplete data. Actually, moderate earthquakes have significant, long-lasting adverse effects in less wealthy areas.

The financial markets agree. In many developing countries, borrowing costs rise a month or two after significant earthquakes, but only if the government is poorly governed and has little savings. If a country is well-run, borrowing costs either stay the same or even drop because investors trust that the country can handle the disaster. So, borrowing costs aren’t really about the earthquake itself. They’re more about what the earthquake shows about how well a country is governed and how much money it has on hand. Disaster relief funding should be set up to show everyone that cash will be available to go to the right places right away if a quake hits.

Barely anyone has insurance, which makes every earthquake feel much worse. In 2024, disasters cost about $318 billion worldwide, but 57% of that wasn’t insured. That leaves a vast $181 billion gap. In many developing countries, over 90% of disaster costs aren’t insured. If you don’t have money set aside, rebuilding competes with paying teachers and keeping hospitals running. The word moderate is misleading. An earthquake is only moderate if the country can afford to fix things without cutting essential programs. Disaster relief funding is there to make that happen.

The Hidden Costs of Messing with Disaster Relief Funding

We see the broken bridge, but it’s harder to see the kid who misses a test, the lost job training, or the environmental damage that hurts farming for years. Right now, we think disasters cost around $202 billion each year directly, but that figure rises to $2.3 trillion if you count everything else affected. The types of costs are essential. Some of the expenses we don’t think about include kids falling behind when schools shut down, people losing income in the informal sector, mental health issues that reduce productivity, and damaged ecosystems that reduce crop yields and harm water quality. Disaster relief funding needs to account for these costs, or it will continue to underfund the real recovery work.

School closures are a good example. In 2024, at least 242 million students in 85 countries had their schooling disrupted by weather and climate issues. Since 2022, extreme weather has forced closures that affected around 400 million students. Earthquakes make this worse when buildings are dangerous or are turned into shelters. This leads to slower learning, more kids dropping out, and bigger problems for students from poor and rural areas. A day off school is often a day of learning lost. Disaster relief funding should protect school time as much as it protects roads. That means having backup plans for safe temporary classrooms, quick repairs, and online learning ready to go, with funds released as soon as the shaking stops.

The last unseen cost is debt. If countries don’t have savings, they have to borrow money in emergencies, which is expensive, takes time, and doesn’t solve the problem for long. This raises borrowing costs, diverts funds from essential services, and makes it harder to return to normal. A recent study shows how disasters, debt, and lack of insurance all make each other worse. It’s a simple cycle. Repeated disasters drain budgets, insurance companies back out, debt piles up, responses are slow, and losses keep growing. Breaking this cycle is the right thing to do and makes financial sense. Small, timely spending before and after a disaster can prevent significant losses later on. Disaster relief funding is how to do it on a big scale.

A New Approach to Disaster Relief Funding

A clear plan for better disaster relief funding includes three main recommendations: 1) Strengthen infrastructure with better building codes, innovative land use, and retrofitting buildings to save lives and reduce damage; 2) Strengthen finances by having funds available quickly, so disasters don't trigger a financial crisis; and 3) Strengthen communities by protecting all families and businesses so everyone can recover. These recommendations have been tested and should be combined into a single, actionable plan with specific steps, defined roles, and clear budgets.

When it comes to money, we need to divide up the risk. Small damages that happen often should be paid out of a reserve fund, which can be used within days. Medium damages should trigger credit lines and pre-set budget support. For large, rare disasters, we should use insurance, risk pools, or catastrophe bonds, in which funds are released based on the intensity of shaking. There are technical guides that explain how to do this and how to use public funds to make sure money moves quickly when needed.

Social support should be designed to kick in automatically during a disaster. Cash payments can be sent to affected areas when shaking reaches a certain level. Payroll support can ensure teachers, nurses, and small business owners are paid during closures. Small grants can be awarded to businesses using simple lists that can be quickly checked. This doesn’t require inventing anything new. Just need budget lines, rules, and data that link hazard information to payment systems. If done right, this is disaster relief funding that helps everyone.

From Schools to Credit Costs: Putting Disaster Relief Funding into Action

Let’s focus on those medium-sized risks. Moderate earthquakes happen a lot. They should be the primary focus when setting up reserves, credit lines, and insurance. Hazard data shows how often these events occur and how much income they cost poorer countries. Planning for them changes how much money we keep on hand, how much we borrow as backup, and how much risk we pass on to the market. It also changes where public money goes first, to schools and hospitals that help families and businesses recover.

Insurance is not a complete fix, but it’s essential. There’s a vast gap globally, and it’s worst in poorer countries, where most losses aren’t insured. Risk pools and public reinsurance can help, but they must be combined with risk-reduction efforts. Otherwise, insurance rates go up, and fewer people get coverage. The numbers also show that markets don’t react as severely to disasters when a country is well-managed and has money on hand. Improving these things further lowers borrowing costs after disasters.

School leaders and local officials need to be involved. School safety checks should be conducted annually and made public. Designs for temporary classrooms and online learning tools should be ready in advance. Contracts for quick school repairs can include triggers for shaking, so funds are released without waiting for damage reports. Teacher salaries should be paid from the duplicate accounts used to pay hospital staff. This might not be flashy, but it's all worth it the moment the first school reopens on time.

Some might say that setting aside money and paying for insurance feels too expensive. But the thing is, not doing it is more expensive and hurts the poor. With disasters costing almost $202 billion each year directly and over $2.3 trillion overall, sticking with the way things are is basically a hidden tax on the poor and slows down growth. Indeed, data and models aren’t perfect. But that’s just a reason to have hazard-based triggers, test our plans, and be transparent – not to wait. Also, markets won’t insure everything. That’s fine. The government's job is to reduce risk and only buy insurance that the markets can afford.

Bottom line: we’re not pricing moderate earthquakes correctly, and poorer countries are paying with slower growth, higher borrowing costs, and kids falling behind in school. The official reports say disasters cause $202 billion in damage each year. The real cost exceeds $2.3 trillion when hidden costs are factored in. Education is a big part of that cost, and it should be part of the solution. Disaster relief funding changes the price signal. It treats frequent disasters as normal, it funds risk reduction before a disaster, and it sends money to schools and hospitals as soon as the shaking stops. That’s how to rebuild risk, not debt.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Arezki, R., Camara, Y., Imam, P., & Kpodar, K. (2025). The economic consequences of earthquakes: A tale from two datasets. VoxEU/CEPR.

Arezki, R., Imam, P. A., Kpodar, K., & Le-Van, D. (2025). When earthquakes shake markets: How investors reassess sovereign risk after natural disasters. VoxDev.

International Monetary Fund. (2019). Building Resilience in Developing Countries Vulnerable to Large Natural Disasters (Policy Paper No. 2019/020).

Swiss Re Institute. (2025). sigma 1/2025: Natural catastrophes—insured losses on a high plateau.

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2025). Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2025: Resilience Pays; “From billions to trillions” news release.

UNICEF. (2025). Global snapshot of climate-related school disruptions in 2024.

World Bank. (2019). Boosting Financial Resilience to Disaster Shocks—Good Practices and New Frontiers (G20 Technical Contribution).

World Bank. (2024, Sept. 4). Education for Climate Action—press release (400 million students affected since 2022).

Comment