Rethinking Market Power and Inflation after the 2021–2022 Shock

Input

Modified

Big firms helped drive the 2021–2022 inflation surge Granular data links market power and inflation Policy and teaching must reflect this granular reality

In late 2022, inflation in the euro area reached a peak of 10.6%. Meanwhile, US consumer prices increased by 9.1% year over year, the highest rate in 40 years. New microdata show that this issue wasn't just about "the economy" in general. In advanced economies, a breakdown of 2.9 billion barcode-level transactions across 16 countries shows that firm-level shocks account for about 41% of inflation variation since 2005. The ten largest firms alone account for 26 percentage points of that total. This research indicates that approximately one-third of the inflation surge in advanced economies during 2021-2022 was driven by this "granular" firm component. Thus, the relationship between market power and inflation involves more than just energy prices or labor market conditions. It also includes how a few dominant firms set prices and wages, manage shocks, and shape inflation expectations for others.

Rethinking market power and inflation after the 2021–2022 shock

The traditional narrative of the inflation surge during 2021-2022 describes it as driven by three forces: supply shocks, high demand, and expectations. A notable analysis using a Phillips curve framework highlights a series of unfortunate events: a COVID-19 shock that closed economies, substantial policy support that boosted incomes, a rapid recovery focused more on goods than services, and subsequent supply bottlenecks and spikes in energy prices. This perspective explains why used-car prices in the US skyrocketed by nearly 50% in 2021. Cars make up less than 10% of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket, but accounted for roughly half of core inflation that year. It also emphasizes that long-term inflation expectations in advanced economies remained largely stable around 2%, suggesting the surge was more of a one-time price shock than the start of a persistent wage-price spiral. In this context, market power and inflation interact only indirectly: firms pass on higher costs when demand is strong, and expectations remain steady if central banks act credibly.

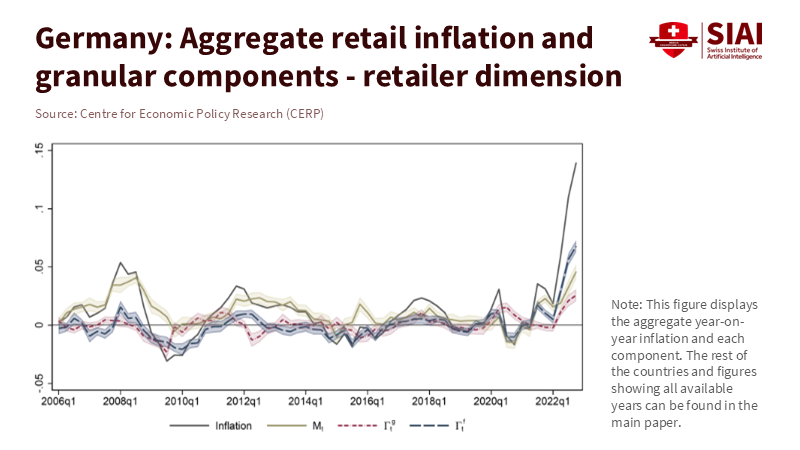

That explanation is crucial, but it treats the corporate sector as a black box. It does not consider which firms actually raised prices, by how much, or what the broader effects were. Recent detailed research opens that box. Across advanced economies, the top 10 firms account for roughly 41% of consumer spending on average. These same firms often change prices across multiple product lines at once, creating synchronized price movements. When researchers split inflation into a "macro" component (the simple average of price changes) and residuals at the firm and product-category level, they find that together, these firm and category residuals account for 56% of inflation variation in advanced economies from 2005 to 2020, with the firm component alone responsible for 41%. In short, market power and inflation converge at a few large companies whose unique decisions can significantly affect overall statistics.

From supply shocks to firm-level price setting in market power and inflation

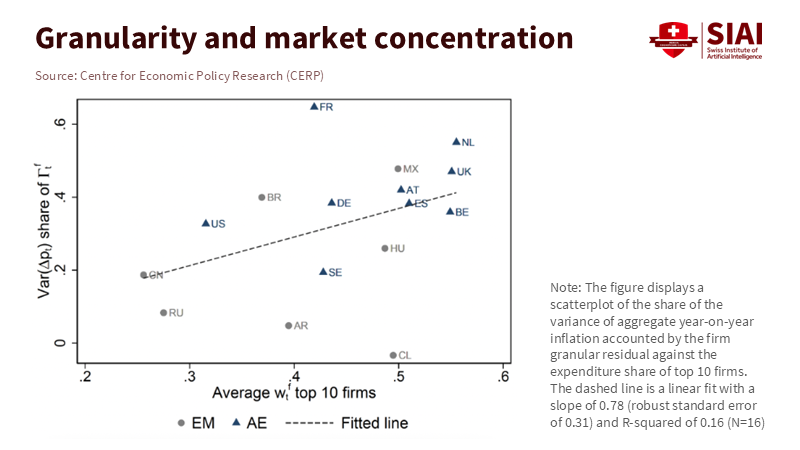

The new "granular" view does not dismiss the importance of supply shocks. Instead, it changes how we understand their economic impact. During the 2021-2022 period, firm-level residuals made up about one-third of the inflation rate in advanced economies, even after accounting for country-level averages. Countries where the top ten firms hold bigger market shares show a more substantial influence from these granular factors. In contrast, economies with more fragmented markets see less impact from individual firms. This suggests that the pass-through of rising energy or import prices varies widely. When a concentrated group of "systemically important price-setters" faces a global cost shock, they tend to adjust their prices together, often across several product lines at once. This results in a significant macro effect. Therefore, the relationship between market power and inflation is structural rather than coincidental.

Evidence on profits supports this point. An IMF analysis of euro area inflation between early 2022 and mid-2023 finds that rising profits account for about 45% of the increase in the consumption deflator, with import costs contributing around 40% and labor costs about 25%. Taxes slightly offset inflation. Profits in absolute terms were approximately 1% above their pre-pandemic trend, while real employee compensation was roughly 2% below it. A separate study in the euro area and Greece using national accounts data concludes that since 2021, domestic inflation has mainly been linked to rising profits, especially in services, where markups increased post-2020. Labor costs played a minor role. Research on inflation in Türkiye from 2018 to 2023 shows a similar trend, with markups nearly doubling, from around 30% to 70%. Price-setting by large firms aimed at protecting profits dominated the inflation process, while wages tended to hold down pressure. Overall, these findings indicate that market power and inflation are connected through firms' ability not just to pass on costs, but also to increase profit margins during a shock.

This shifts the understanding of the typical expectation-driven wage-price spiral. Standard accounts suggest that workers push for higher wages after prices rise, which in turn drives prices up. However, recent research shows that wage changes lag behind prices, with profits seeing the most significant early gains, not wages. In concentrated markets, boards and pricing committees at a few dominant firms set wages and prices based on their expectations of future costs, demand, and policy. Therefore, inflation expectations are not solely influenced by households and bond traders; they also stem from strategies employed by large firms with significant markups and diverse product lines. The cycle of "prices up → wages up → prices up" is more accurately described as "big-firm prices up and margins widened → partial wage catch-up → another round of price decisions by the same firms." This is the essence of the connection between market power and inflation during the 2021-2022 period.

Policy lessons: market power and inflation in a concentrated economy

Suppose firm-level factors and profits matter this much. In that case, it may be tempting to recommend a simple policy solution: fragment industries to prevent a few firms from causing the next inflation spike. Granular evidence supports this instinct to an extent. In emerging economies, where markets are less concentrated and inflation tends to be structurally higher for other reasons, firm and category residuals explain only about 20% of inflation variation, compared to 56% in advanced economies. This suggests that in more fragmented markets, individual firms play a minor role in overall inflation. However, fragmentation isn't without costs and isn't a complete solution. Decades of research on "superstar firms" show that the growth of dominant companies is linked to scale economies, intangible assets, global supply chains, higher markups, and a declining labor share. Simply breaking up large firms without a broader strategy could harm productivity and slow innovation, while failing to address inflation.

Instead, the granular evidence suggests a more focused policy approach. Competition authorities should view large price-setting firms in crucial sectors—energy, food retail, logistics, and digital platforms—as "systemically important" for inflation, much as some banks are seen as necessary for financial stability. This calls for ongoing scrutiny of mergers and acquisitions that raise already high levels of concentration, careful monitoring of pricing practices during economic shocks, and a willingness to use tools against abusive dominance when necessary. Transparency regarding profit margins is also essential. When profits account for nearly half of price increases during a shock period, as they did in the euro area, public discussion should not focus solely on wages and government deficits. Windfall-profit taxes or temporary price caps may be needed in sectors with substantial evidence of markups influencing market power and inflation. Still, these measures must be carefully crafted to avoid distorting investment and supply.

Granularity is also vital for the design of monetary policy. New evidence reveals that in the US and the euro area, the short-run "price puzzle" that follows a rate hike—where inflation initially rises—comes almost entirely from these granular components, not from the macro average. Large firms seem to raise prices more aggressively when rates rise, possibly to protect profit margins amid rising financing and input costs. Over time, the macro component behaves as textbooks suggest, but the short-term path is influenced by the interaction of market power and inflation within a concentrated corporate framework. This indicates that central banks in highly concentrated economies may need to maintain tighter policies for longer to counter slow pass-through, or to combine rate hikes with macroprudential and competition tools that limit opportunistic pricing. It underscores the importance of high-frequency price microdata from large firms for forecasting inflation and determining whether profits, wages, or external costs are primarily affecting inflation in a given quarter.

Teaching market power and inflation for the next generation

For educators, the key takeaway is not to overhaul macroeconomics entirely, but to shift the focus. Introductory courses still need to cover the Phillips curve, the impact of supply shocks, and the central bank’s role in managing expectations. The evidence that inflation in 2021-2022 was driven by significant commodity and supply shocks, combined with strong post-pandemic demand, remains solid. However, teaching this narrative without incorporating the role of firm-level actors gives students an incomplete view of market power and inflation. A better approach would be to develop case-based modules tailored to specific sectors such as cars, energy, food retail, and big tech. In each instance, students could explore how changes in input prices, logistics, or demand affect the prices set by a few large firms. They could also examine the responses of profits and wages, and how these aggregate into the CPI.

At more advanced levels, programs aimed at training future central bankers, regulators, and policy analysts should include granular tools as standard. Students should learn to interpret inflation breakdowns that show contributions from import prices, profits, and labor costs, similar to the euro area analysis that divided the recent surge into approximately 40% import costs, 45% profits, and 25% labor costs. They should also see how firm-level data can estimate the inflation variance explained by large companies, and how market concentration interacts with cost pass-through and the effects of monetary policy. At the intersection of macroeconomics and industrial organization, teaching can highlight both the advantages and risks of market concentration: the benefits from scale and the vulnerabilities that arise when a few firms become the main channel through which shocks affect households. This is where the fundamental dynamics of market power and inflation become apparent.

For both policymakers and educators, the aim is not to convert every lesson into a technical exercise. It is to clarify the inflation debate. When students recognize the connection between supermarket prices, energy bills, and decisions made by a few powerful firms, they better understand why specific shocks feel so sudden and unjust. When they see profits rise while real wages decline during the early phases of recent inflation, they grasp why inflation's distributional impacts have become so contentious. And when they observe inflation has decreased close to target in the euro area—from 10.6% in October 2022 to around 2–2.5% in 2024–2025—they can appreciate the role of policy in managing expectations and demand, even in a granular context.

The conclusion is straightforward but challenging. Controlling inflation cannot fall solely on the shoulders of central banks, and it cannot be viewed merely through the lens of aggregate shocks. The 2021-2022 episode illustrates that a small number of large firms, wielding significant market power, can account for a considerable share of both inflation variance and overall inflation during a shock. Future frameworks need to recognize these firms as key players in the inflation process, rather than as mere background noise. This requires updating educational approaches, enhancing competition policy, improving access to detailed price data, and crafting monetary and fiscal tools that account for the interconnectedness of market power and inflation. If the next generation of students learns to view inflation through both macro and granular lenses, the next inflation surge might not catch society off guard.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Alvarez-Blaser, S., Auer, R., Lein, S. M., & Levchenko, A. A. (2025). The granular origins of inflation. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 19844.

Autor, D., Dorn, D., Katz, L., Patterson, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2020). The fall of the labor share and the rise of superstar firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Bank of Greece (2024). Inflation dynamics and the role of domestic factors. Economic Bulletin, December 2024.

Hansen, N.-J., Toscani, F., & Zhou, J. (2023). Euro area inflation after the pandemic and energy shock: Import prices, profits and wages. IMF Working Paper 2023/131.

Hansen, N.-J., Toscani, F., & Zhou, J. (2023). Europe’s inflation outlook depends on how corporate profits absorb wage gains. IMF Blog, 26 June 2023.

Necip, B., & Yılmaz, E. (2025). Inflation dynamics: Profits, wages and import prices. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics (in press).

Ubide, Á. (2022). The inflation surge of 2021–22: Scarcity of goods and commodities, strong labor markets and anchored inflation expectations. Intereconomics, 57(2), 93–98.

Eurostat (2022). Annual inflation up to 10.6% in the euro area (October 2022). News release 130/2022.

Eurostat (2025). Annual inflation up to 2.4% in the euro area (December 2024). Euro indicators release, 17 January 2025.

European Central Bank (2024). Recent inflation developments and wage pressures in the euro area. Economic Bulletin, Issue 2.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics (2022). Consumer prices up 9.1 percent over the year ended June 2022. The Economics Daily, 13 July 2022.

OECD (2024). Consumer prices, OECD – statistical release, 4 December 2024.