AI Readiness in Financial Supervision: Why Central Banks Move at Different Speeds

Published

Modified

AI readiness in financial supervision decides who adopts fast and who falls behind In 2024, only 19% used generative tools, with advanced economies far ahea Fund data and governance, scale proven pilots, and measure real outcomes

Only one number frames the debate: nineteen. In 2024, about 19% of countries were using generative AI tools in financial supervision, up from 8% the previous year. The trend is clear. Jurisdictions with better skills, data, and governance frameworks move faster and further; those without these resources fall behind. The result is not just a technology gap; it is a readiness gap linked to income levels and government capacity. In advanced economies, supervisory AI relies on robust data pipelines and model risk rules. In many other parts of the world, limited computing power, weak data, and small talent pools delay adoption and increase risk. If we want AI to improve oversight everywhere—not just where the infrastructure is already in place—we need to treat “AI readiness in financial supervision” as a public good, measure it, and fund it with the same focus we give to capital and liquidity rules.

AI readiness in financial supervision is the new capacity constraint

The global picture is inconsistent. By 2024, three out of four financial authorities in advanced economies had deployed some form of supervisory technology. In emerging and developing economies, that figure was 58%. Most authorities still depend on descriptive analytics and manual processes, but interest in more advanced tools is growing rapidly. A recent survey found that 32 of 42 authorities are using, testing, or developing generative AI; around 60% are exploring how to incorporate AI into key supervisory workflows. Still, the proportion of countries using generative tools in supervision stood at just 19% in 2024. Adoption is happening, but readiness remains the primary constraint.

Broader government capability metrics tell the same story. The 2024 Government AI Readiness Index puts the global average at 47.59. Western Europe averages 69.56, while Sub-Saharan Africa averages 32.70. The United States leads overall, yet Singapore excels in the “Government” and “Data & Infrastructure” pillars—the essential foundations supervisors need. These rankings are not just for show; they indicate whether supervisory teams can build data pipelines, manage third-party risk, and validate models effectively. Where these pillars are weak, projects stall, and regulators stick to manual reviews. Where they are strong, supervisors can adopt safer and more understandable systems and use them in daily practice.

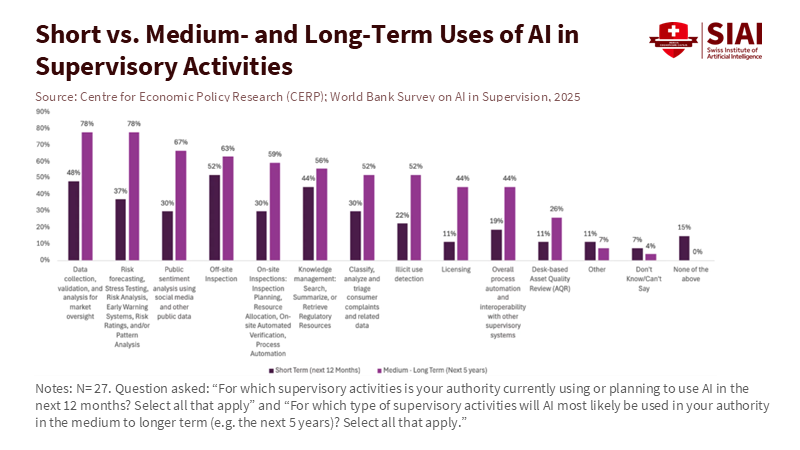

What the data say in 2023–2025

Recent findings from regulators in emerging and developing economies confirm the existence of a readiness gap. Most authorities are still in the early stages of using AI for core tasks like data collection, off-site inspections, and anomaly detection. Basic generative tools are standard for drafting and summarizing, but structured uses for supervision are rare. Only about a quarter of surveyed authorities report having a formal internal AI policy today; in Africa, this share is closer to one-fifth, though many plan to implement policies within a year. The main barriers are clear: data privacy and security, gaps in internal skills, concerns about model risk and explainability, and the challenge of integrating AI into old systems. These are the same issues that readiness indices highlight.

Complementary BIS survey work shows how processes and culture widen the divide. In 2023, 50 authorities from 45 jurisdictions shared insights on their “suptech” activities. Only three had no initiatives at all, but the types of activities varied greatly by income level. Authorities in advanced economies were about twice as likely to host hackathons and collaborate across agencies. Most authorities still develop tools in-house, but the use of open-source environments is low, especially in emerging markets. This matters. Collaboration and open tools reduce costs and speed up learning; their absence forces each authority to start from scratch. The issue is not a lack of ambition in emerging markets. It’s that readiness—skills, processes, and governance—determines the pace.

Risk is another important factor. Supervisors are right to be cautious. The Financial Stability Board warns that generative AI introduces new vulnerabilities: model hallucinations, which are instances where the AI model generates incorrect or misleading data; third-party concentration, cyber risk, and pro-cyclical trends if many firms use similar models. The report’s message is cautious but significant: many vulnerabilities fall within existing policy frameworks, but authorities need better data, stronger model risk governance, and international coordination to keep up. Supervisory adoption cannot overlook these constraints; it must incorporate them from the beginning.

Closing the gap: from pilots to platforms

The first task for authorities with low readiness is not to launch many AI projects. It is to turn one or two valuable pilots into shared platforms. Start with problems where AI truly helps, not just impresses. Fraud detection in payment data, complaint triage, and entity resolution across fragmented registries are good areas to focus on. They utilize data the authority already collects, deliver clear benefits, and strengthen core capabilities—data governance, MLOps, and model validation—that future projects can also use. This is how the most successful supervisors transition from manual spreadsheets to reliable pipelines. It is also how they build trust. Users prefer tools that reduce tedious work and provide results they can easily explain.

Financing and procurement must support this approach. Smaller authorities cannot cover the fixed costs of computing and tools on their own. Regional cloud services with strong data controls, pooled purchases for red-teaming and bias testing, and code-sharing among peers lower entry costs and improve quality. The BIS survey shows strong demand for knowledge sharing and co-development; we should respond with practical solutions. For example, we can standardize data formats for supervisory reports and publish reference implementations for data ingestion and validation. Another approach is to fund open, audited libraries for risk scoring that smaller authorities can build on. These are public goods that maximize limited budgets and enhance safety.

Standards, safeguards, and measuring what matters

Rules and metrics determine whether AI is beneficial or harmful. Authorities need three safeguards before any model impacts supervisory decisions. First, a clear model-risk policy that aligns materiality with explainability. Low-impact tools can utilize opaque methods with strong oversight; high-impact tools must offer understandable results or be paired with robust challenger models. Second, strict third-party risk controls should be in place from procurement to decommissioning. Many jurisdictions will depend on external models and systems; contracts must address data rights, incident reporting, and exit strategies. Third, disciplined deployment: maintain an active inventory of models, log decisions, and monitor changes with documented re-training. The goal is simple: keep human judgment involved and ensure the technology is auditable.

Measurement should go beyond counting pilots. We should track the time to inspection, reporting backlogs, and the proportion of alerts that lead to supervisory action. Where possible, measure the false-positive and true-positive rates, as well as the differences between the challenger and production models. Connect these operational metrics to readiness scores, such as the IMF’s AI Preparedness Index and the Oxford Insights Index. If an authority’s “data and infrastructure” pillar improves, backlogs and errors should decrease. If they do not, the issue lies in the design, not the capability. The benefits of getting this right are significant. The IMF estimates that spending on AI by financial firms could more than double from $166 billion in 2023 to around $400 billion by 2027; without capable supervisors, that investment could pose new risks faster than oversight can adapt.

We started with nineteen—the proportion of countries using generative AI in supervision last year. That number is likely to increase. The question is who will benefit from this growth. If adoption follows readiness, and readiness correlates with income, the gap will widen unless policies change. The way forward is clear and practical. Treat AI readiness in financial supervision the way you treat regulatory capital. Invest in data and model governance before pursuing new use cases. Share code, data formats, and testing methods internationally. Use readiness indices to set baselines and targets, and hold ourselves accountable for meaningful outcome metrics for citizens and markets. AI is not a replacement for supervisory judgment; used correctly, it enhances it. The next wave of adoption should demonstrate this by moving faster where the foundations are strongest and building those foundations where they are weakest.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (BIS) (2024). Building a more diverse suptech ecosystem: findings from surveys of financial authorities and suptech vendors. BIS FSI Briefs No. 23.

Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2024). The Financial Stability Implications of Artificial Intelligence. 14 November.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2024). “Mapping the world’s readiness for artificial intelligence shows prospects diverge.” IMF Blog, 25 June. (AI Preparedness Index Dashboard).

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2025). Bains, P., Conde, G., Ravikumar, R., & Sonbul Iskender, E. AI Projects in Financial Supervisory Authorities: A Toolkit for Successful Implementation. Working Paper WP/25/199, October.

Oxford Insights (2024). Government AI Readiness Index 2024. December.

World Bank / CEPR VoxEU (2025). Boeddu, G., Feyen, E., de Mesquita Gomes, S. J., Martinez Jaramillo, S., et al. “AI for financial sector supervision: New evidence from emerging market and developing economies.” 18 November.

Comment